The 4th Yebisu International Festival for Art & Alternative Visions

‘How Physical’

February 10-26, 2012

Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography

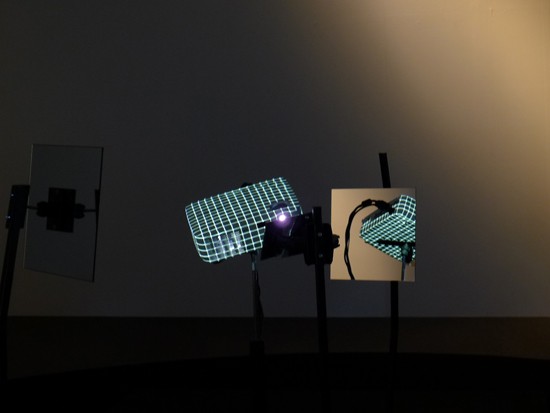

Carolien Teunisse and Bram Snijders [Sitd] – RE: (2010), 360°projection mapping installation. All images: Photo ART iT.

Carolien Teunisse and Bram Snijders [Sitd] – RE: (2010), 360°projection mapping installation. All images: Photo ART iT.For those who remember last year’s “Daydream Believer!!” and 2010’s “Searching Songs,” the theme of the 4th Yebisu International Festival for Art & Alternative Visions had the unfortunate association of evoking Olivia Newton-John’s camp 1981 hit “[Let’s Get] Physical.” Although the Japanese version of the theme, Eizou no fijikaru, could have been translated more directly to “the physicality of images,” which might have at least avoided what one would assume to be an unintended connotation, there was little in the exhibition itself that could assert a more meaningful understanding of the curatorial framework.

Indeed, the idea of “physicality” was alternately too specific or too open-ended with regard to the works. Both made using technically impressive “crane shots” that impart a visceral floating sensation, Marijke von Warmerdam’s two-channel projection Couple (2010), in which a camera circles an elderly couple sitting on a bench overlooking a river amid a verdant garden, and Yuan Goang-ming’s three-channel projection Disappearing Landscape – Passing II (2011), with multiple cameras simultaneously passing through a family home, a forest, a water channel and other landscapes, seem to address more the idea of optics and the illusory space of images rather than physicality per se. On the other hand, in his recent short film Other Faces (2011), William Kentridge in an almost sculptural way experiments with the physicality of how images are constructed. Loosely relating the events surrounding a car accident in Johannesburg, the hand-drawn animation interweaves scenes of the city’s street life and its monuments and architecture into a fantastic narrative that communicates the fraught tensions of a still racially divided society. But Kentridge also uses devices such as animation within the animation, which in the narrative becomes a film “projected” onto an outdoor backdrop, as well as hints of the artist’s actual creative process – suggested, for example, by the edges of a work table bordering another sequence of images otherwise composited on a single paper surface – to fracture and recompose the diegetic space of the film.

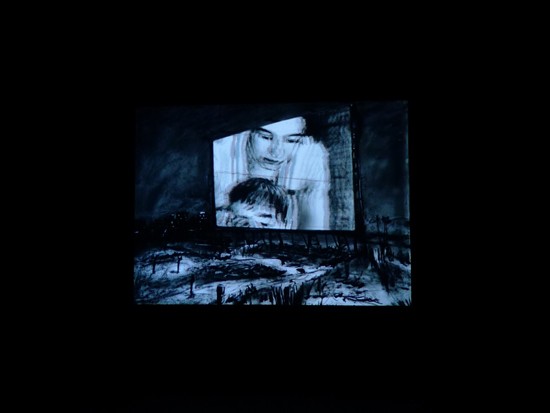

Top: Yuan Goang-ming – Disappearing Landscape – Passing II (2011), three-channel video installation (sound, color), dimensions variable, 9 min. Bottom: William Kentridge – Other Faces (2011), single-channel video (sound, color), 10 min.

Top: Yuan Goang-ming – Disappearing Landscape – Passing II (2011), three-channel video installation (sound, color), dimensions variable, 9 min. Bottom: William Kentridge – Other Faces (2011), single-channel video (sound, color), 10 min.Illustrating the potential of the “hand-made film,” the combination of narrative impact and innovative expression manifested in Other Faces could have been a rich vein of physicality to expand upon and counteract through other works, all the more so as we enter an era in which the 3D effects and digital renderings of studio productions implicitly define the moving image as a terrain of technical proficiency and massive resources, off-limits to anyone without the most advanced skills and capital, even as the actual ability to produce films is more democratized than ever through the popularity of digital cameras and smart phones. Instead, this implication gets lost in relation to works ranging from Julius von Bismarck’s The Space Beyond Me (2010), in which an automated 16mm film camera projects UV light images – of a naked man walking through a romantic landscape – around a darkened, circular chamber, to an archival presentation of educational science films produced in the 1950s and ’60s by Tokyo Cinema Co, shot in handsome 35mm color film with nostalgic vintage voiceover narrations, like Beer (1954) and The World of Microbes: In Quest of the Tubercle Bacilli (1958).

Similarly, the exhibition’s basement level is dedicated to projects that engage with the intersections between images and architecture, namely the multimedia installation Experience in Material No 53: DUBHOUSE KINO (2012) by the architect Ryoji Suzuki, which is both a large-scale model of a building and a labyrinthine projection surface, and the film Points on a Line (2010) by Sarah Morris, dedicated to two icons of American Modernism, the Farnsworth House by Mies van der Rohe and the Glass House by Philip Johnson. This too could have been an interesting sub-theme to expand further, but as realized only appends another possible association to the “Physical” of the exhibition title, without building upon or clarifying those that come before it.

Top: Ryoji Suzuki – Experience in Material No 53: DUBHOUSE KINO (2012), wood, acrylic lacquer, tempered glass, hard rubber, aluminum, steel, plywood, floor support, drawings, projector, model 570.5 x 574.5 x 365 cm. Bottom: Sarah Morris – Points on a Line (2010), single-channel video installation (sound, color), 35 min 44 sec.

Top: Ryoji Suzuki – Experience in Material No 53: DUBHOUSE KINO (2012), wood, acrylic lacquer, tempered glass, hard rubber, aluminum, steel, plywood, floor support, drawings, projector, model 570.5 x 574.5 x 365 cm. Bottom: Sarah Morris – Points on a Line (2010), single-channel video installation (sound, color), 35 min 44 sec.From the physics of film technology to the materiality of film itself and the dimensionality of the spaces in which it is presented or of the spaces and processes that it can capture, it felt throughout the exhibition that the framework of “How Physical” was always at one remove from what the works could potentially communicate, as though it were simply a convenient catch-all. Certainly it should be noted that the exhibition proper was only one component of the festival, which also included a screening program of works by artists including Jonas Mekas, Walter de Maria and Tony Conrad, and compendiums like “The Art of Flight: Physicality of Action Sports Movie Today” and “Deep Structure – Korean Contemporary Art.” But the exhibition is also the one arena where the festival’s curatorial team can put forward a cohesive statement on what they find to be interesting, compelling or simply current about images today, and in this sense this year’s edition was ultimately disappointing and insipid compared to the promise of previous editions.