Takashi Azumaya – the ‘being and temperature’

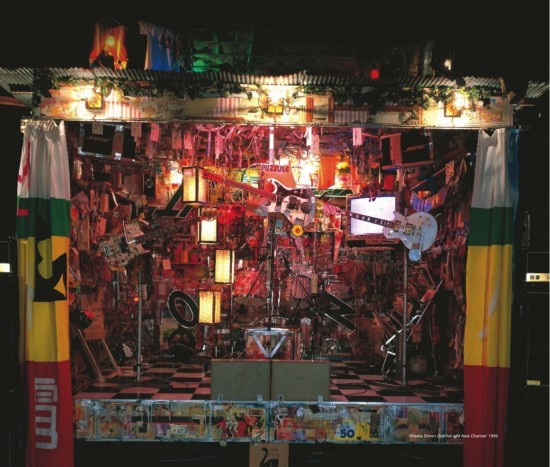

Shinro Ohtake – Dub-Hei & New Chanel (1999) (detail). Installation view at “Art/Domestic – Temperature of the Time” (Setagaya Art Museum, Tokyo) Photo: Masataka Nakano, courtesy Setagaya Art Museum.

Shinro Ohtake – Dub-Hei & New Chanel (1999) (detail). Installation view at “Art/Domestic – Temperature of the Time” (Setagaya Art Museum, Tokyo) Photo: Masataka Nakano, courtesy Setagaya Art Museum.The independent curator Takashi Azumaya has passed away. He was just 44 years old.

I first met him all of 22 years ago. I had been invited to Tokyo University of the Arts for the first time to give a special lecture, and I took with me a draft of my first collection of essays, Simulationism (1991), which had yet to be published. The lecture went on for over three hours, and for the second half I was joined by the graphic designer Hiroshi Nakajima, who also works as a DJ. This approach was clearly unprecedented for a lecture at “Geidai.” After I finished speaking, a number of students came up to me somewhat excitedly, and among them was Azumaya.

It was not until later, however, that I found out the student in question was Azumaya. It was at Röntgen Kunst Institut, the stronghold of the new generation of artists that opened near Haneda Airport a short time after that lecture, and which went on to produce in succession such artists as Takashi Murakami and Makoto Aida. At the time Azumaya was still an aspiring artist who carried around files of his own work. On the day in question he had a piece in which the singer Madonna had become pregnant, with Azumaya himself playing the part of the fetus inside a giant womb. Looking back on it now, I still think it was dreadful. But I remember thinking right away that, while there were still aspects of him that were unrefined, Azumaya had the potential to become an extraordinary artist. Ultimately, however, he abandoned the idea of becoming an artist and at some point set his sights on becoming a curator. At the Setagaya Art Museum, where he took up his first curatorial position, he was involved in organizing a large number of projects in which numerous innovative musicians (among them Tony Conrad and Mani Neumeier) were invited to participate, and while I went along to many of these partly due to the fact that I was living in Setagaya at the time, at this stage he had yet to be given the opportunity, it seems, to organize an exhibition on his own.

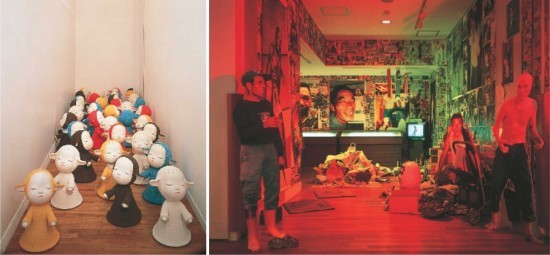

Then, completely out of the blue, I got a phone call from Azumaya. He was about to organize his very first exhibition at the Setagaya Art Museum. He wanted to invite Takashi Nemoto to participate, and was eager to know more about “909 – Anomaly 2,” an exhibition I curated in 1995 at Röntgen Kunst Institut that featured Nemoto, and to this extent the purpose of the call was to canvas my thoughts (or rather, to seek my advice). This project eventually came to fruition in 1999 as “Art/Domestic – Temperature of the Time” (featuring Atsuko Tanaka, Shinro Ohtake, Yoshitomo Nara, Yuichi Higashionna, Masami Tada, Hiroyuki Ohki and Takashi Nemoto). With Atsuko Tanaka’s painting setting the underlying tone, the exhibition featured prominently the work of artists such as Ohtake and Nara who have a close relationship with rock music, and with the inclusion of the installation work of Tada, another artist with a close connection to music; Ohki, a young artist who is also involved in film; Higashionna, who makes use of light, color and pattern to produce an optical experience somewhere between design and art; and the outsider manga artist Nemoto, the result was an exhibition the likes of which a public art museum in Japan had never seen or ever will see again. Events held during the exhibition included a “collaboration” between Yamataka Eye of The Boredoms and Ohtake’s installation, and at the opening a mystery person Nemoto interviewed while working on his piece strutted around the museum, all of which ensured every moment of the exhibition was filled with a raw tension that was very much the “temperature of the time.”

Left: Yoshitomo Nara – The Little Pilgrims (Night Walking) (1999). Right: Takashi Nemoto – The Core Behind the Exhibition Temperature of the Time / Chaotic Neighbors (1999). Installation views at “Art/Domestic – Temperature of the Time” Photo: Masataka Nakano, courtesy Setagaya Art Museum.

Left: Yoshitomo Nara – The Little Pilgrims (Night Walking) (1999). Right: Takashi Nemoto – The Core Behind the Exhibition Temperature of the Time / Chaotic Neighbors (1999). Installation views at “Art/Domestic – Temperature of the Time” Photo: Masataka Nakano, courtesy Setagaya Art Museum.The inclusion of the words “Art/Domestic” in the English title of this exhibition was an acknowledgment by Azumaya that in art there was a measure best described as a domestic “temperature” discernible only to those people whose eyes were fixed on the place where they lived, which was undoubtedly impaired by cooled-down “international (global)” theory and history, and that it was his job as curator to visualize this. Furthermore, in publishing in 1998 Nihon・Gendai・Bijutsu (Japan/Modernity/Art) and curating at the end of the same year as “Art/Domestic” what could be called an exhibition version of that book at Art Tower Mito, titled “GROUND ZERO JAPAN,” I was seeking to “reset” Japanese “contemporary art” in the wake of Nemoto and reform the “post-war art” landscape itself, and for this reason I had high hopes for Azumaya, the curator of “Art/Domestic – Temperature of the Time,” whom I regarded as an unconventional kindred spirit. In light of this, one could regard “Art/Domestic – Temperature of the Time” and “GROUND ZERO JAPAN” as companions in the context of what was one of the major currents of the times.

A photo taken at the time of “Art/Domestic – Temperature of the Time.” From left to right: Shinro Ohtake, Takashi Nemoto, Yoshitomo Nara, Atsuko Tanaka, Masami Tada, Yuichi Higashionna, Hiroyuki Ohki (all participating artists) and Takashi Azumaya. Photo courtesy Chieko Azumaya.

A photo taken at the time of “Art/Domestic – Temperature of the Time.” From left to right: Shinro Ohtake, Takashi Nemoto, Yoshitomo Nara, Atsuko Tanaka, Masami Tada, Yuichi Higashionna, Hiroyuki Ohki (all participating artists) and Takashi Azumaya. Photo courtesy Chieko Azumaya.“Art/Domestic – Temperature of the Time” gave rise to among other things the Shinro Ohtake masterpiece Dub-Hei & New Chanel, but above all it deserves praise for shining a light fairly and squarely on Atsuko Tanaka as a painter in her own right. In this regard, the omission (whether deliberate or not I do not know) of “Art/Domestic – Temperature of the Time” from the main chronology at the start of the solo exhibition “Atsuko Tanaka: The Art of Connecting,” held in early 2012 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, was a major blunder. This is because it was undoubtedly the pioneering work of Takashi Azumaya that freed Tanaka, who is currently attracting a great deal of interest in the international art world, from the “Gutai” label that was habitually used to describe her at the time, and afforded her for the first time the public recognition she deserved.

After “Art/Domestic – Temperature of the Time,” however, Azumaya promptly left the Setagaya Art Museum. I am not aware of the details surrounding his departure. He later joined the organizing committee of the first Yokohama Triennale and served as a curator at the Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery and the Mori Art Museum, both of which have become central to the contemporary art scene in the metropolitan area (Azumaya often said, half-jokingly, “No other curator has followed as elite a course in Japanese contemporary art as I have.”), eventually going on to tread the path of the “independent curator,” a path he chose himself. I think this was also a challenge to the Japanese art environment of the kind only Azumaya could contemplate, to see if it were possible to continue curating exhibitions without belonging to a specific organization.

During this period, Azumaya curated “Gundam: Generating Futures” (which showed at the Suntory Museum in Osaka before travelling to other venues, 2005-07) and was a guest curator for the 2008 Busan Biennale before returning to the same biennale in 2010 as artistic director, the first such appointment for Azumaya at an international exhibition. In terms of our involvement together, two exhibitions that I will never forget are Shinro Ohtake’s “Dub-Kei” in Osaka (KPO Kirin Plaza Osaka, 2000), which I invited Azumaya to curate, and “OP Trance!” (KPO Kirin Plaza Osaka, 2001), which we co-curated on the basis of our common interest in optical art. In addition, in 2003 when I established together with Masanori Oda and others the anti-Iraq War unit Korosu-na (Do Not Kill), Azumaya was one of the leading contributors along with people like Muneteru Ujino and Fuyuki Yamakawa, appearing on stage rain or shine playing his black single-string guitar and pulling his mini amplifier on casters. I undertook various other activities with the people from Korosu-na, including a live performance of John Zorn’s “game” piece Cobra (Tokyo Operations Korosu-na Party, Leader: Noi Sawaragi, November 2003,Yamamoto Gendai), and as an extension of these protest activities we journeyed as far afield as the Onbashira festival in Suwa and Mount Osorezan on the Shimokita Peninsula, and Azumaya accompanied us on every occasion. Late one night when we shared the same karaoke box, it was Azumaya who entertained everyone the most. Altogether, while on the one hand he was always a step ahead of the times with his bold concepts, on the other he was full of careful consideration for those around him, and above all full of boundless affection for each and every artist he worked with. It is unlikely we will ever see another curator like him. Thinking about this makes me feel hopelessly sad.

Looking back dispassionately over Azumaya’s career as a curator, however, I get the feeling there was nothing that surpassed that first exhibition, “Art/Domestic -Temperature of the Time.” For this very reason I cannot help but imagine what it would have been like if he had been given the opportunity to bring to fruition the “Art/Domestic – Temperature of the Time 2” exhibition he had been talking about before his death. But he never did bring it to fruition. I wonder why. Perhaps it was because of the poor state of his mental and physical health, which had become conspicuous from a certain time. Or perhaps it was because of the intolerance of the Japanese art world, which was incapable of providing a being like Azumaya whose “body temperature” went up and down so dynamically with a grand stage commensurate with his ability.