Learning a lesson from ‘trick art’

Taking my first day off for a while – and deciding a soak in a hot spring would be just the ticket – I jumped in the car and headed for the Nasu-Shiobara area to see what I could find. Amid all the souvenir shops and tourist spots rendered eerily quiet by the March 11 earthquake and tsunami, just one place was doing a roaring trade, its car park close to bursting. Instinctively I eased up on the accelerator and took a look. On the roadside was a large sign declaring this to be the “Pavilion of Trick Art.” Fancy that, I mused, such a thing still exists. For old times’ sake I went in…and found the place heaving with people. Families, young dating couples, what looked suspiciously like middle-aged cheating couples on dirty weekends…in other words a wondrous variety of humanity, all having a wonderful time wandering around the museum and eagerly snapping souvenir shots. I had no idea that trick art, which seemed to largely disappear for a few years, had made such a remarkable comeback. And this despite the entry fee, not cheap at 1300 yen.

Now when I say “trick art,” I doubt the gentle readers of ART iT, let alone anyone reading this outside of Japan, will have any idea to what I’m referring.

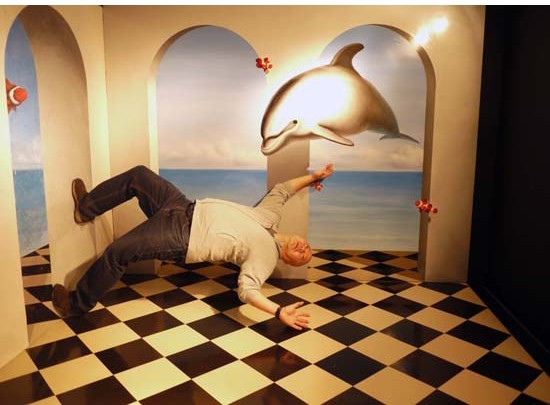

Trick art is the art of rendering the two-dimensional, ie flat, as three-dimensional, ie solid.

Art in which new technologies and ideas are added to conventional techniques for making pictures look three-dimensional – that is perspective, chiaroscuro and combining advancing and retreating colors (trompe-l’œil) – resulting in astonishing illusions of perception.

These illusions create a surprisingly natural feeling of three-dimensionality.

(From the official website at www.trickart.co.jp)

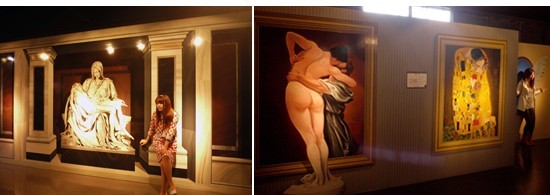

More specifically we’re talking about an art-themed tourist attraction, where famous classical paintings, sculptures, buildings, etc, are rendered as three-dimensional-looking murals that visitors can view, touch and even become part of by taking photos with figures and backdrops.

Trompe-l’œil is widely recognized as a familiar technique employed for centuries in European art. You may also know it as a technique especially loved by the Surrealists. Originally it was a kind of intellectual game involving fun with optical illusions, but trick art, while based on conventional trompe-l’œil, pushes the playful aspect one step further, in a pursuit of optical illusion as entertainment that actually has its origins in Japan.

The first trick art is credited to an artist by the name of Kazumune Kenju. Born in 1940 in Yamagata, Kenju resigned from his job at the Yamagata Bank at the age of 38 to launch a career as an environmental designer. As well as a number of painted works that merge beautifully with their surrounding environments, such as the giant “Hill of Creation” mural in Kashiwazaki, Niigata, his projects included a series of parodies of famous paintings, and after much stopping and starting, in 1991 the first trick art location: the JAIB Museum in Shinozakicho, Edogawa-ku (closed in 1998). Incidentally, “JAIB” is from the English “Jack-in-the-box.”

The JAIB Museum was completely ignored by the art world, but widely covered in the mass media, for example on TV and in magazines, as a “new concept in tourist attractions.” I’m sure a second museum emerged the following year in Shibuya, and due to the ease with which they could be established, from then on suddenly there were “trick art pavilions” springing up all over Japan. Running here and there covering the regions at the time, I remember being amazed to encounter these places everywhere I went.

Kazumune Kenju devised a communal production system modeled on the studios of the Renaissance, and churned out an impressive volume of work. Motifs were dominated by well-known Western paintings, but the unique thing was Kenju’s production method. For a start, rather than oil pigments, he used industrial oil-based paints. And, what’s more, a mere five colors, which he blended to produce subtle variations and used to paint even the most massive murals with a single flat brush. Commercial paint was his chosen material because any marks from being touched by visitors could easily be washed off. When you see an example of the real thing, it’s hard to believe it has been produced by throwing together just five colors, so beautifully are the subtle variations of the original reproduced.

As head of the studio he’d founded, SD, Kenju went on to open one trick art museum after another through the 1990s, but then died in an accident in 1997 while working on a project to reproduce the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel in 3/5 scale at the “Nastina Museum” he’d opened in Nasumachi. Working on the ceiling alone one night, he fell and was apparently found on the floor the next morning, but the Sistina – or rather “Nastina” – went on to glorious completion, and today is the most popular attraction at what is now known as Michelangelo’s Pavilion.

Kenju’s studio staff continued to turn out trick art even after his death, but due perhaps to the lingering recession following the collapse of Japan’s post-war bubble economy, as I mentioned earlier the museums that had sprung up across the nation began to close in quick succession. Personally, I’m thrilled to see them now enjoying such a revival.

Despite their grand title of museum, these trick art pavilions are perceived by the world as nothing more than second-rate tourist attractions. Kazumune Kenju, the father of trick art, died without being recognized by the art fraternity as an artist. He did however leave the following words:

Art museums are not the property of just a few. They should be more accessible places that everyone can enjoy: those with artistic inclinations, those without; adults, children.

A dozen or so trick art museums are still in business around Japan, and with Kenju’s studio based in Nasu, unsurprisingly three of these establishments, run directly by SD, can be found in the town: the Trick Art Pavilion, a trick art labyrinth, and Michelangelo’s Pavilion. These places are totally foreign, have always been totally foreign, and will no doubt remain totally foreign to art aficionados – beings of such intellect and learning – but I do recommend paying even just one visit if the opportunity arises. Just look at those young people excitedly taking photos with the likes of Da Vincis, Michelangelos and Caravaggios (albeit reproductions); the children scampering about, squealing in delight. Ask yourself, could you really tell them to their faces how wrong they are to get so excited by fakes?

For me at least, this fake art akin to a fruitless blossom flowering unobtrusively in a corner of the Far East is not to be dismissed with a sneer, but celebrated as teaching us something of great value.