Allow me first to offer my heartfelt condolences to all those suffering as a result of the recent massive earthquake and tsunami. I hope life can return to some kind of normality in a safe environment as soon as possible.

As the aftershocks continue, not only are art museums in the affected areas closed for the time being, even outside the disaster zone one exhibition after another is being canceled or postponed. We may ask what use art can possibly be at a time like this, but whatever the answer, the reality is that there is no way it can match the efforts of former self-styled outlaws loading trucks with kerosene for delivery to soldiers and firefighters on the frontline, or the young tonkotsu (pork bone) ramen guy who packed a portable cooking stove into his HiAce and drove up from Kyushu to prepare food for the afflicted. If one were to paint a picture, how would that picture be received by the estimated 200,000 individuals affected by the disaster? I suspect that right now, not a few of us (including this writer) have been forced to fundamentally rethink what it means to call oneself an artist.

From towns wiped out by the tsunami and nuclear power stations spewing sinister smoke, to babies plucked out of the ruins by the arms of soldiers, in the past couple of weeks we have been swamped by a veritable tsunami of information, a constant barrage of photographs and video footage. Of all these images of disaster, that which more than any other jolted me to the core was not a clip of television footage, or a photo spread in a weekly magazine, but a single painting produced by Mizuki Shigeru for the New York Times.

A right hand reaching out of swirling water as if about to be swallowed up by the muddy torrent. Fingers straining outstretched in a desperate struggle. In contrast to the sentimental media chorus exhorting us to “join together and rise again,” Mizuki’s is a stark, powerful work that grabs us – we humans prone to avert our gazes from horrific reality – by our collective throats, and forces us to face what has actually occurred. That such a work is the creation not of some fashionable contemporary artist, but an aging cartoonist, also gives much pause for thought.

When I saw Mizuki’s picture I was instantly reminded of a small park in the Tokyo district of Ryogoku. Known as Yokoamicho Park, in a previous incarnation it was Hifukusho-ato, the former site of an army-clothing depot and a place of terrible tragedy where 38,000 people died in the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923.

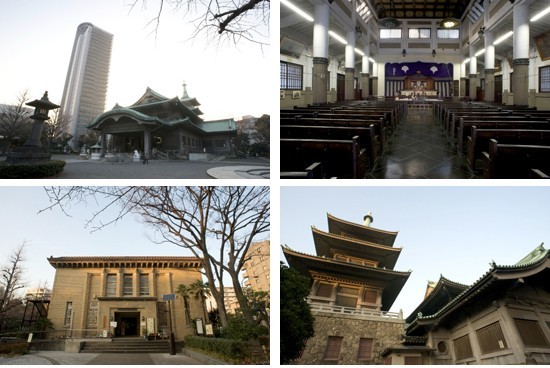

Top left: View of the Tokyo Hall of Repose. An eclectic blend of Western and Japanese architecture combining a hall in front and three-tiered pagoda behind. In the background is the NTT DoCoMo Sumida Building. Top right: The vast interior of the hall, which resembles the combination of a Gothic church and the main hall of a Buddhist temple. Bottom left: View of the Reconstruction Memorial Hall. Bottom right: This area was devastated in the bombing of Tokyo, but miraculously both buildings survived the war unscathed.

Top left: View of the Tokyo Hall of Repose. An eclectic blend of Western and Japanese architecture combining a hall in front and three-tiered pagoda behind. In the background is the NTT DoCoMo Sumida Building. Top right: The vast interior of the hall, which resembles the combination of a Gothic church and the main hall of a Buddhist temple. Bottom left: View of the Reconstruction Memorial Hall. Bottom right: This area was devastated in the bombing of Tokyo, but miraculously both buildings survived the war unscathed. Yokoamicho Park is home to two buildings, the Tokyo Metropolitan Hall of Repose and the Reconstruction Memorial Hall. Few know that enshrined here are the ashes of around 163,000 people, victims of the Kanto Earthquake and air raids of World War II.

Right at lunchtime on September 1, 1923, at 11:58 am, the Great Kanto Earthquake, generated in Sagami Bay, struck the Japanese capital. People ran about in a desperate attempt to flee the city, some with just the clothes on their backs, others pushing their household belongings in handcarts. Most in the Ryogoku neighborhood congregated here. Back then it was an open space, a huge lot vacated by a factory that had made army uniforms. Purchased by the city of Tokyo, work was underway to turn it into a park.

Around 40,000 people evacuated to the former factory site, but a fire started somewhere among the sea of humanity and household effects crammed into the space, and with nowhere to run, people were swept up in the flames. Around 38,000 were burnt to death. Out of the just over 100,000 lives said to have perished in the Great Kanto Earthquake, almost four out of ten were killed here by fire. In the gathering of bodies and bones that began the next day, the pile of corpses is said to have reached over three meters high.

This ossuary was built to hold the remains of 58,000 unidentified, incinerated people, and act as their memorial. The historical information in the park states that “construction of the hall began in September 1930 under the supervision of architects including Chuta Ito, in a public-private collaboration using funds raised from multiple sources, and was gifted in its entirety to the city of Tokyo by the Tokyo earthquake memorial association.”

The Hall of Repose was built in the hope that such a disaster would never again occur, but as is well known, during World War II Tokyo was battered by bombing raids, no less than 106 of them. In particular, March 10, 1945, saw over 300 B29s descend on the city from late the night before until the early hours of that morning, turning working class districts of Tokyo – base for the military supply industries – into a raging inferno. Over 77,000 people lost their lives on that night alone. Corpses incinerated beyond recognition were temporarily buried at 130 temples and parks around the city. After the war, starting in 1948, they were then disinterred by the city authorities over a period of four years and re-cremated at facilities around the city. Of the victims, 105,000 other than those fortunate enough to be identified and claimed by bereaved families were gathered in this hall in 1952. In Tokyo, military dead are enshrined at places such as Chidorigafuchi and Yasukuni Shrine, but for civilians, there is no place other than this.

Both: Inside the ossuary, where the remains of 163,000 people are enshrined. Each urn contains the ashes of around 200 individuals.

Both: Inside the ossuary, where the remains of 163,000 people are enshrined. Each urn contains the ashes of around 200 individuals.The Hall of Repose currently houses the remains of a combined 163,000 victims of the Great Kanto Earthquake and Tokyo air raids. Of these the ashes of the around 3,700 of whom the sex and name are known are kept in individual urns, while the rest lie in large urns each containing the remains of around 200 people, on the ground floor of the Hall. These rows of startlingly capacious urns are stacked neatly almost to the ceiling of the dimly lit room. This is what the remains of 160,000 people look like.

The ossuary is not usually open to the public, but the hall – resembling a Gothic church attached to a three-tiered pagoda – is open all the time, and can be visited by those wishing to pay their respects. Two large memorials for the earthquake and air raids sit at the altar, but most noteworthy are the oil paintings of the Kanto Earthquake hung on either side.

Top left: Victims swept up in the fire whirl. Top right: Chaotic disaster scene, and a self-portrait of the artist Ryushu Tokunaga. Bottom left: Painting showing the destruction of the building known colloquially as the “Junikai” that towered above Roku-ku in Asakusa. Bottom right: Priests praying at a pile of remains cremated outdoors at the Hifukusho-ato site.

It is widely known that at the time of the Great Kanto Earthquake, postcards appeared depicting the resulting hellish devastation, but the massive oil paintings produced by the painter Ryushu Tokunaga and his apprentices with titles such as The Former Hifuku-sho, Destruction of the Junikai and Whirlwind have a horrific intensity in their no-holds-barred rendering of the terrible damage wrought by the earthquake. Nor should one overlook the series of air raid photos taken by Koyo Ishikawa, a photographer attached to the police agency during the war. The government had restricted photographing of the bombing devastation by the general public, so Ishikawa’s photos became the sole record of the largest raids over Tokyo, the photographer burying the priceless negatives in his garden rather than bow to demands from Allied Powers commander Douglas MacArthur’s post-war administration to hand them over.

Top: Pile of incinerated corpses from a Tokyo air raid, photographed by Koyo Ishikawa. Bottom: Second floor display space of the Reconstruction Memorial Hall.

Top: Pile of incinerated corpses from a Tokyo air raid, photographed by Koyo Ishikawa. Bottom: Second floor display space of the Reconstruction Memorial Hall.The Reconstruction Memorial Hall next to the Hall of Repose was completed in 1931, the year after the Hall. Like the Hall, the sturdy, two-storey ferroconcrete structure is the work of Chuta Ito. The ground floor of the Memorial Hall houses documentary photographs and paintings of the Great Kanto Earthquake, and exhibits such as burned everyday items. The second floor presents exhibits on assistance sent from overseas and the major air raids over Tokyo, as well as displays on post-war earthquakes and other subjects.

Forming the nucleus of the display is a collection of artworks and materials presented at an exhibition to mark the capital’s recovery, staged in autumn of 1929 prior to completion of the Hall of Repose and the Reconstruction Memorial Hall. Here one finds everyday items transformed into objets d’art rendered in pitch-black ash, and the ruins of buildings. Posters produced in the United States, Italy and other countries urging their citizens to come to the aid of Japan. A model street layout of a “new Tokyo” assembled for the exhibition. Of particular interest are the numerous large canvases depicting scenes from the disaster, the painters’ determination to engage head-on with the subject matter obvious in an era when paintings still had a significant documentary function.

Canvas after canvas documenting the Great Kanto Earthquake.

Noticed by no one – not the children playing innocently in the park, nor their mothers dwelling in the surrounding high-rise apartments, nor the salarymen mellowing out on benches – in their silence the collection of quake paintings adorning the walls of the Hall of Repose and Reconstruction Memorial Hall seem to have something urgent to say to those of us – artists in particular – now paralyzed in the face of Japan’s worst natural disaster since the Great Kanto Earthquake.

Tokyo Hall of Repose / Reconstruction Memorial Hall

Yokoamicho Park, 2-3 Yokoami, Sumida-ku, Tokyo

9am – 4:30pm (closed Mondays)