Stranger on the Road

By Hu Fang

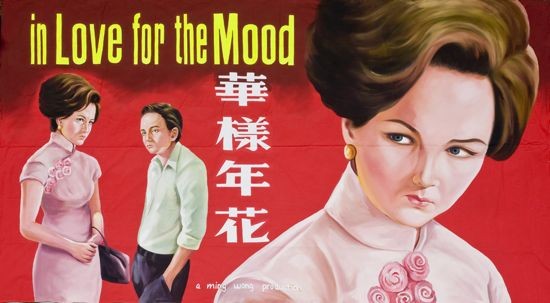

Cinema billboard designed by Ming Wong, painted by Neo Chon Teck (2009), variable dimensions, acrylic emulsion on canvas. All images: Courtesy Ming Wong.

Cinema billboard designed by Ming Wong, painted by Neo Chon Teck (2009), variable dimensions, acrylic emulsion on canvas. All images: Courtesy Ming Wong.Word Order

Many of Ming Wong’s work titles invert a given word order:

Life & Death in Venice (2010) vs. Death in Venice (Luchino Visconti, 1971)

Life of Imitation (2009) vs. Imitation of Life (Douglas Sirk, 1959)

In Love for the Mood (2009) vs. In the Mood for Love (Wong Kar-Wai, 2000)

Angst Essen / Eat Fear (2008) vs. Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1974)

In this re-writing of their titles, the original movies slide into an uncanny rebirth. Every time images from the movies are reincarnated in our own lives – every time there is a coincidence between the movies and ourselves – a new life comes into being.

Through Ming Wong’s process of reenactment, these images, which both preserve and exceed consumption, take on new life.

Life and Death

Video still from Life & Death in Venice / Leben und Tod in Venedig / Vita e Morte a Venezia (2010).

Video still from Life & Death in Venice / Leben und Tod in Venedig / Vita e Morte a Venezia (2010).From its opening scene, Visconti’s Death in Venice manifests a metaphoric landscape: set against the soundtrack of Gustav Mahler’s brooding Adagietto, a lonely boat carries the protagonist, the composer Aschenbach, toward life’s opposite shore. In contrast, Ming Wong’s Life & Death in Venice opens against the backdrop of a common tourist city, with the artist, dressed as Aschenbach, attracting the curious glances of tourists as he passes through St. Mark’s Square.

Ming Wong places the protagonists in a “real” contemporary setting, where avid cultural tourists are visiting for the Venice Biennale, and then not only uses the city but also the Biennale venues for his locations. Aschenbach and the beautiful youth Tadzio wander through a labyrinth of contemporary art, but this does not alter their individual, parallel fates. At the climax of Ming Wong’s version, the beautiful youth still turns toward heaven and raises his fatal finger to the sky. This scene appears twice, whereas in the original Death in Venice it appears only once, fleetingly.

With Ming Wong playing both roles, this inevitably becomes a kind of performance of split personality, and because of this split consciousness, the opposition between the exhaustion and beauty of life in Death in Venice suddenly disintegrates; now, the youth’s gesture toward heaven is no longer a fatal strike against the middle-aged composer, but rather its antithesis: a pose of reconciliation. Accordingly, through its death in film, art earns an everlasting life.

Acting

And how does Ming Wong achieve a parasitic relationship with other people’s lives in his films?

He acts.

He plays all the roles.

In Four Malay Stories (2005), he plays the roles of characters from the once-popular films of the Malaysian director P Ramlee: a doctor, a lover, a soldier, a singer…

In Angst Essen / Eat Fear, he plays both the Moroccan immigrant worker Ali and the German laundress Emmi who in spite of their differences in age and ethnicity become lovers; at the same time, he also plays the people who oppose their relationship.

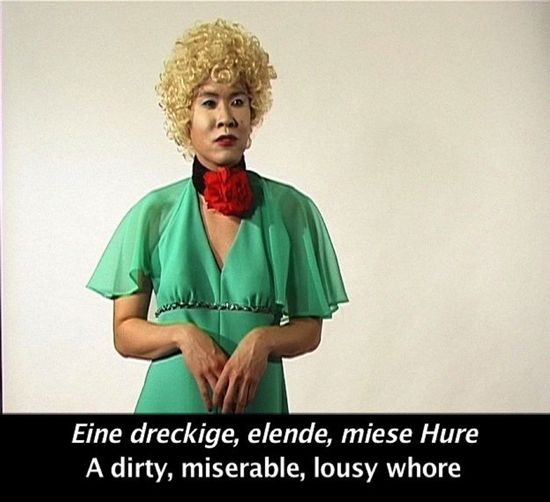

In Lerne Deutsch mit Petra von Kant (2007), he plays the heart-broken German woman from Fassbinder’s The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972).

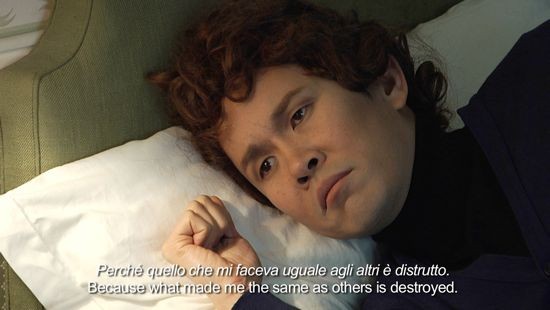

In Devo Partire. Domani. / I must go. Tomorrow. (2010), he plays the guest, the father, the mother, the son, the daughter and the maid from Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema (1968).

Ming Wong also makes other people act.

In In Love for the Mood, he has a Caucasian actress from New Zealand play the role of So Lai-zhen, portrayed by the Chinese actress Maggie Cheung in Wong Kar-wai’s original film.

In Life of Imitation, he has a Chinese, a Malaysian and an Indian actor each take turns playing the roles of Sarah Jane and her mother from the original film.

While these performances appear to imitate imagery from preexisting films, they are also a catalyst for the exercise of memory. They are a fresh rehearsal of images that formerly existed in the minds of the audience.

Ming Wong’s genius of performance lies in his ability to capture not only form, but also the significance of the portrayal and re-portrayal of form. And so life is reborn through the deviations that appear in his particular re-rehearsal.

Identity

Ming Wong plays all the roles: male, female, young, old, Malaysian, German, Moroccan; but what is interesting is that he has yet to play a Chinese person.

In his book Identity and Violence: The Illusion of Destiny, Amartya Sen wrote:

The same person can be, without any contradiction: an American citizen, of Caribbean origin, with African ancestry, a Christian, a liberal, a woman, a vegetarian, a long-distance runner, a historian, a schoolteacher, a novelist, a feminist, a heterosexual, a believer in gay and lesbian rights, a theater lover, an environmental activist, a tennis fan, a jazz musician and someone who is deeply committed to the view that there are intelligent beings in outer space with whom it is extremely urgent to talk (preferably in English). Each of these collectivities, to all of which this person simultaneously belongs, gives her a particular identity. None of them can be taken to be the person’s only identity or singular membership category.

I think this is related to the carnival of life. Is it not? An Asian person wearing a blonde wig to play the divinely beautiful youth Tadzio, while at the same time playing the composer Aschenbach who walks toward death – this in itself has an aspect of carnivalism, and tests the limits of individuality. What it suggests is that the space of images has the potential to stretch and expand the limits of individual life, and can in fact produce a collective life.

Pronunciation

Video still from Lerne Deutsch mit Petra Von Kant (2007).

Video still from Lerne Deutsch mit Petra Von Kant (2007).In Four Malay Stories, Ming Wong parrots Malaysian; in Lerne Deutsch mit Petra von Kant, he exerts himself in learning German; in Devo Partire. Domani, he studies Italian.

He also makes other actors mimic foreign languages: in In Love for the Mood, he has a native English speaker mimic Cantonese speech.

Ming Wong once self-mockingly said that when he was producing Lerne Deutsch mit Petra von Kant, he had just moved to Berlin and was a 35-year-old, single, gay, minority, mid-career artist, and that he poured the bitterness and desperation he felt at the time into his pronunciation of the line, “Ich bin im Arsch.”

Using clearly flawed accents, Ming Wong reveals the awkwardness of imitation. Disinclined to the process of fully inhabiting the character, he instead finds his own voice from within the cracks of different language systems.

Billboards and Cinemas

In making his project Life of Imitation for the Singapore Pavilion at the 2009 Venice Biennale, Ming Wong rediscovered hand-painted movie billboards, as well as their gradual disappearance in Singapore.

He tracked down the last remaining billboard painter in Singapore, Neo Chon Teck, and commissioned him to make posters for the pavilion.

The disappearance of the hand-painted billboards also signifies the disappearance of a certain style of cinema in Singapore. The cinemas of Singapore’s golden age in the 1950s and ’60s have now been turned into shopping centers, housing complexes, churches and karaoke parlors. Ming Wong used Polaroid film to document these golden-age cinemas – their glorious pasts, fading presents and uncertain futures all become, in these instantaneous snapshots, specimens that the artist has rescued from time.

In an interview, Ming Wong described his feelings towards Singapore as follows: “Singapore’s urban landscape is constantly changing; all the architecture is brand new, you won’t see any old things at all here. I feel this has a major effect on the memory of the people, and a major effect on the memory of self-identification. We don’t know who we are. We are always changing, chasing, progressing. You don’t know whether or not this is real progress, or whether this is all about ‘becoming the other,’ or even ‘willfully becoming the other.'”

Mirror Images

Watching and being watched, and constantly watching again.

In his film installations, Ming Wong imbues time and space with a new degree of uncertainty, in order to question and yet stimulate the ceaseless wavering of the spectator between the poles of desire and distance.

For the installation of Life of Imitation, mirrors opposite two video monitors refract parallel and never-crossing worlds, and in In Love for the Mood, the triplicate images recurring across the installation’s staggered arrangement of three monitors reflect the multilayered variants and false-starts of passion.

In Ming Wong’s film installations, reflections are not only illusions but also suggest and reproduce the depth of time, mirroring the slight transformations and variations of time. Thus images that originate from the “other” slowly merge with Ming Wong’s own life.

Ming Wong’s filmic productions are always intertwined with the circumstances of his life at any particular moment, ingeniously reflecting his own personal experiences. His works are not only related to the reconstruction of the memory of filmic time, they are also, in a sense, his autobiographical restaging of the contemporary maturation process of an artist.

It is just as the artist has said: “We are projected into an unidentifiable space and time where flashbacks and flash-forwards seem prone to occur.” What Ming Wong confronts is the brief super-imposition of his self and other people in the reflections of the world.

Teorema

Video still from Devo partire. Domani / I must go. Tomorrow (2010).

Video still from Devo partire. Domani / I must go. Tomorrow (2010).A beautiful stranger mysteriously enters the home of a bourgeois Italian family, and following that stranger’s mysterious departure, the family members experience dramatic changes in their lives: the son quits his studies to become an artist, the father leaves home, the mother rediscovers her sexuality…

In his remake of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema, what Ming Wong re-enacts are the instants when the family’s five members each lose their senses of identity. A Singaporean “stranger,” he directs and acts out the family members’ different life paths.

In reinterpreting other people, do we recover our own identities? Or is it the opposite, in that it is only through losing our identities that we can recover them?

Or, do we long for all of these possibilities to converge in one body, and bring us an endless current of vitality?

In Pasolini’s Teorema, the son realizes: “I don’t recognize myself anymore. Because what made me like the others is destroyed. I was just like anybody, with so many faults perhaps, mine and those of the world. You made me different, have taken me out of the natural order of things…What will become of me from now on? What will the future be like living with a me that hasn’t anything to do with me?”

Life, without a theorem. Sometimes even the slightest leverage can change your life completely.

Can we not say that we are all strangers in life?

Translated from the Chinese by Andrew Maerkle

Ming Wong‘s solo exhibition “Life of Imitation” is currently on view at the Singapore Art Museum through August 22. Wong is participating in the upcoming 8th Gwangju Biennale, “10,000 Lives,” at multiple venues in Gwangju from September 3 to November 7, and his solo exhibition, “Gruppenbild,” opens at the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein on September 28, continuing through November 5.

Hu Fang is a fiction writer and co-founder of Vitamin Creative Space, Guangzhou, as well as the shop, Beijing. His latest book is the novel Garden of Mirrored Flowers (co-published by Sternberg Press and Vitamin Creative Space).