Dan Cameron reviews Massimiliano Gioni’s recently opened Gwangju Biennale

Sanggil Kim – off‐line_burberry internet community (2004), C-print, 134.5 x 163.5 cm. © Sanggil Kim, courtesy PKM Gallery | Bartleby Bickle & Meursault.

Sanggil Kim – off‐line_burberry internet community (2004), C-print, 134.5 x 163.5 cm. © Sanggil Kim, courtesy PKM Gallery | Bartleby Bickle & Meursault.Since its debut in 1995, the Gwangju Biennale has typically been a sprawling, exuberant affair. Initiated by the city in commemoration of the massacre of hundreds of protestors at the hands of Korea’s military dictatorship in 1980, the biennial has frequently had a populist edge, its stated goal to recognize art’s unique potential to uplift and transform the general populace. In one memorable edition in 2004, members of the public were invited to “co-curate” the exhibition by making specific requests to the organizers concerning what art they would like to see in a biennale (one innocently requested Leonardo da Vinci). In the 2008 edition, headed by Okwui Enwezor, a local open-air market was transformed, for 60 memorable days, into a bustling artsy micro-bohemia.

This year’s biennial is as different from its predecessors as night from day. Stunningly curated by Massimiliano Gioni and bearing the title “10,000 Lives,” the 8th Gwangju Biennale takes as its inspiration the epic literary work of the same name by Ko Un, a monk-poet-activist who was imprisoned following the Gwangju Uprising and used his time behind bars to reflect on all the people, living and dead, he’d encountered in his life to that point. Gioni’s twist is to reflect on the photographic image as a proof of life, deftly upending the post-modern convention of the mediated image as inherently false, or at least moderately untrustworthy. With some 120 artists, many either deceased or more closely identified with the past century than the current, it’s the show’s epic desire to offer a sweeping curatorial report on the current state of the visual image that provides the closest affinity to the earlier editions.

In many ways, Gioni’s edition doesn’t look or feel like a biennial at all. There are few commissioned or site-specific works; no large-scale public projects; nothing located beyond the tight perimeter of the Biennale Hall and three adjacent spaces; and many of the works on view don’t quite qualify as art. Not surprisingly, “10,000 Lives” overwhelmingly privileges photography, film and video, to such an extent that much of the painting and sculpture seems out of place. As many viewers commented during the opening weekend, “10,000 Lives,” with its overtones of Edward Steichen’s landmark “Family of Man” exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1955, is the kind of broad survey one yearns to see in a major museum. Perhaps more aptly, by combining art from the recent past, art by outsiders, new art and non-art, with a careful sidestepping of critical distinctions between such categories, Gioni is helping himself to the rich legacy of the late Swiss curator, Harald Szeemann.

Installation view of Carl Andre’s War & Rumors of War (2002) in foreground and Gu Dexin’s 2009-05-02 (2009) at the 8th Gwangju Biennale. Photo ART iT.

Installation view of Carl Andre’s War & Rumors of War (2002) in foreground and Gu Dexin’s 2009-05-02 (2009) at the 8th Gwangju Biennale. Photo ART iT.For this very reason, “10,000 Lives” is one of the most viscerally thrilling encyclopedic exhibitions in years. Conceived as a one-way circuit in which viewers are subtly prevented from doubling back over a previously explored area, and where the exit is deliberately far from the entrance, the layout functions as a stand-in for the trajectory of a single human life, or, if you prefer, all human lives. As corny as that description might read, it works brilliantly. A helpful guidebook walks us from the entrance, where a suite of photos by Sanggil Kim offers deadpan witness to what happens when members of subject-specific Korean online chat groups (one devoted to Burberry, another to the Sound of Music) are brought together offline; to an austere ending comprised of Emma Kunz’s otherworldly healing-diagram drawings from the 1930s-40s. In between, we are driven at breakneck speed through screenings of Japanese experimental film and video from the 1950s, posthumous installations by 1960s New York avant-gardists Stan Vanderbeek and Paul Sharits, the death of Che Guevara (in a work by Leandro Katz), the assassination of Bobby Kennedy, Pol Pot’s massacres, Tiananmen Square, suicide bombers, 9/11 (in the form of newspaper headlines collected by Hans-Peter Feldmann) and, in one heart-wrenching video by Yasmine Kabir, the ongoing illegal marketing of Bangladeshi migrant labor in countries like Malaysia.

The deepest pleasures of “10,000 Lives” are tied to Gioni’s emergence as one of the most gifted exhibition designers working today, and the viewer passes through room after room of encounters that are superbly considered and arranged. Anne Collier’s slideshow of images based on Faye Dunaway’s performance in the 1978 film The Eyes of Laura Mars faces off against a video from 2002 by Arnoud Holleman using slowed-down archival footage of a Dutch Protestant sect who refused to allow themselves to be photographed well into the 1960s. In a stunning but not atypical room, Carl Andre’s monumentally oblique War and Rumors of War (2002) is encircled by a harrowing anti-manifesto of large printed texts by Gu Dexin, who renounced making art in 2009 after completing the work on view.

That isn’t to say “10,000 Lives” is without flaws, some more serious than the rest. While certain areas of confusion can be attributed to the inherently slippery theme, others spotlight bad curatorial habits. Gioni, who is not known for discovering or nurturing emerging talent, betrays a dismayingly heavy bias toward successful artists and powerful dealers and collectors. At its most innocent, this means one trudges past the usual quota of unconvincing works by biennial staples like Carsten Höller, Pawel Althamer, Maurizio Cattelan, Fischli & Weiss, Bruce Nauman, Bridget Riley, Cindy Sherman, Thomas Hirschhorn and James Lee Byars, to name a few.

Ydessa Hendeles – Partners (The Teddy Bear Project) (2002), installation view at Haus der Kunst, Munich. 3000+ family-album photographs; antique teddy bears with photographs of their original owners and related ephemera; mahogany display cases; 8 painted steel mezzanines; painted portable walls; hanging light fixtures and custom wall lighting. Photo Robert Keziere, courtesy Ydessa Hendeles and the Ydessa Hendeles Art Foundation, Toronto.

Ydessa Hendeles – Partners (The Teddy Bear Project) (2002), installation view at Haus der Kunst, Munich. 3000+ family-album photographs; antique teddy bears with photographs of their original owners and related ephemera; mahogany display cases; 8 painted steel mezzanines; painted portable walls; hanging light fixtures and custom wall lighting. Photo Robert Keziere, courtesy Ydessa Hendeles and the Ydessa Hendeles Art Foundation, Toronto.A telling example of this privileging of the already privileged is Partners, an installation in the Biennale Hall of more than 3000 vintage photographs of people holding teddy-bears, presented by the Toronto collector Ydessa Hendeles. While the idea is not without its charm, part of the requirement for the collection’s display was apparently that the walls and staircase of the collection be transported to Gwangju, and the installation match the original down to its smallest detail. Unfortunately, giving this project the attention one might a gigantic gesamtkunstwerk does not justify itself in rewards for the viewer, not least of all because the actual installation is so poorly lit as to be nearly unviewable.

A different kind of fiasco unfolds just around the corner from Partners in Gioni’s three-room tribute to Mike Kelly’s 1993 project The Uncanny, originally made for that year’s Sonsbeek International Sculpture Exhibition in Arnhem, Holland. Where Kelly’s original installation of photographs, objects and artworks from disparate sources (in which this writer spent a memorable afternoon) was sprawling, densely cluttered and overwhelming, its “unauthorized” reconstruction in Gwangju is antiseptic, mannered and visually awkward. Had the Paul McCarthy sculptures of reclining, half-dressed figures in the Folk Museum been included in The Uncanny, and the works by Paul Thek, Tetsumi Kudo and John Miller already on display in this section been better fleshed out so that one could get a grasp of these artists’ respective oeuvres, the rooms might have had more impact.

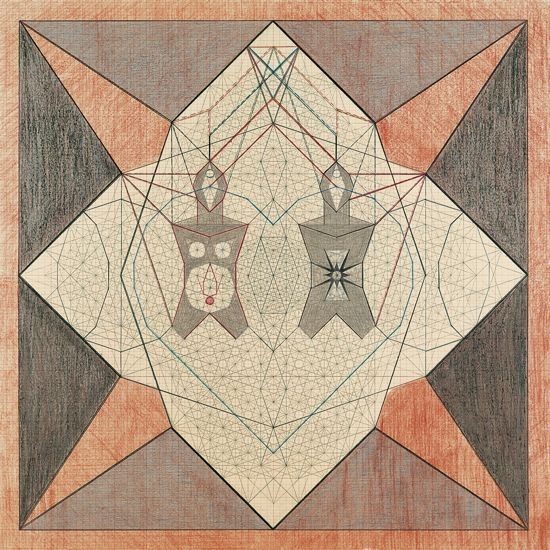

Emma Kunz – Drawing No. 086 (Undated), pencil and crayon on white scale paper, 92 x 92 cm. © Anton C Meier, Emma Kunz Foundation, Würenlos, Switzerland.

Emma Kunz – Drawing No. 086 (Undated), pencil and crayon on white scale paper, 92 x 92 cm. © Anton C Meier, Emma Kunz Foundation, Würenlos, Switzerland.A more telling problem emerges when one considers certain concerns stirred up by his theme: Gioni’s Eurocentric perspective. There is one artist each, respectively, from South America and Southeast Asia, and none at all from Africa, Australia or major countries like India and Russia. These kinds of rations are uncomfortably reminiscent of the era before “Les Magiciens de la Terre,” the landmark 1989 exhibition that introduced the notion of global art to the world, and rendered obsolete (or had until now) sweeping curatorial projects that refused to engage art produced in less industrialized nations. Again, it’s partly as a result of Gioni’s having set the bar so high, and having pulled off such fruitful research into Japanese, Chinese and Korean art of the recent past, but considering that a few chunks of “10,000 Lives” do read as visual filler, the question arises of how the exhibition’s theme might have been illuminated further if, instead of attempting to frame as art things that are merely interesting, the curator had shown he was even vaguely curious about how the other three-fifths of the planet sees itself.

The 8th Gwangju Biennale, “10,000 Lives,” continues at multiple venues through November 7.