Dan Cameron on his personal Image Archive and its role in his curatorial practice

Courtesy Dan Cameron.

Most curators are, at their core, collectors of a sort, and recently I have decided to come to terms with the fact that for more than 25 years, I have been surreptitiously engaged in creating what I think of as one of the most comprehensive archives of contemporary art in the world. Not only do I supplement it on a regular basis, I also find that whenever I need to do in-depth research into an artist’s work, it’s the first place to turn. It’s even occurred to me that the only reason any of my other work is even possible is because I made a commitment many years ago to keeping this collection as up to date as possible. Although it contains many different sorts of material, I call my collection the Image Archive because that best sums up its contents.

The Image Archive was started during my first years as a curator and art writer in the early 1980s, when it became clear that if I were to dutifully attend all the museum, gallery and alternative space exhibitions worth seeing in New York City, I would soon amass so much information about contemporary art that it would eventually surpass my ability to keep it all organized without some kind of reference system. I was being exposed to so much art in such a condensed period of time – and at a time of such radical transformation within the art system – that I also craved a physical record of the changes I was witnessing firsthand as I made my way through hundreds of exhibitions each year. Artists and movements would come and go, but somehow the archive would supersede them, encompass them, and make them all strangely equivalent to each other.

Most importantly, if I was going to spend the rest of my life writing about and organizing exhibitions of contemporary art, it was essential to have a reference system that worked for me. Gradually I developed a method of categorizing the contents of the Image Archive so that it helped me keep things organized, but did not require so much attention as to take time away from the projects it was meant to support. Here is the system I developed:

1) The Image Archive is alphabetized by individual artists who live and work anywhere in the world. Those no longer alive are moved to a parallel archive of Deceased Artists, where Leon Golub and Louise Bourgeois now rest alongside Picasso and van Gogh. Files are created only for those artists whose work has actually caught my attention – a number that at present includes approximately 1400. I do not otherwise discriminate by way of genre, country of origin, or generation: any artist whose active dates overlap with my own and whose work I don’t genuinely dislike has a file. There are a couple of ancillary boxes filled with examples by artists whose work is sort of intriguing, but not enough yet for a file of their own. An adjacent bulletin board is reserved for anonymous and unidentified images (especially photographs), or images ascribed to artists whose names have never come to my attention more than once.

2) Each time I attend a solo exhibition, I try to take away a printed card containing an image of the artist’s work, which eventually goes in the archive. Whenever I open the mail at home or the office, I set aside all announcements with an image of an artist’s work on them to go into the archive (people who work with me get used to the accumulating cardboard boxes that periodically vanish to upstate New York). If I come across an article in an old newspaper or art magazine about an artist whose work interests me, into the archive it goes. Nothing added to the archive is scanned; all the material rests there in the form (photocopy, newsprint, card) I first encountered.

3) Besides the Deceased Artists’ archive, several years ago I created separate, subject-based archives to complement the work of the Image Archive. The largest of these is the Group Show file, which contains hundreds of announcements and checklists for group exhibitions that other curators have organized throughout the world (if I copy them, at least I’m not doing so out of ignorance). There are also meta-subject files, like East Village and Politics & Art, that seem to grow steadily over the years; as well as genre files of developments over the decades in Architecture, Film, Dance, Theater, Literature and – by far the biggest – Music.

But why archive, especially in the Age of Google? For a time, especially during a few lean years, I would mentally entertain the scenario of hurling the whole thing into the dump. It seemed too self-involved, too obsessive-compulsive, too similar to the dreaded hoarding behavior of an urban kook. Besides, considered from the standpoint of somebody who bought his first Macintosh SE in 1987 and never looked back, wasn’t the digital revolution supposed to change everything? Wasn’t all information supposed to be available soon at the touch of a finger?

Setting aside the fairly obvious revelation that archiving is formational to the way my mind processes art, a pair of curatorial projects in recent years have demonstrated how the archive’s existence can be a godsend. In 2005, while still at the New Museum, I put together a sprawling group exhibition, “East Village USA,” which tracked that epoch’s peak in the 1980s and included work by more than 45 artists. Not only did I begin my research with individual files on nearly all of the artists already in hand, but I’d saved all the articles I read on the subject of East Village art at the time by Nicholas Mouffarege, Gary Indiana, Roberta Smith, Carlo McCormick, Paul Taylor and Collins & Milazzo. In addition, I possessed the flyer and checklist for every East Village-themed exhibition of the period, from the ICA Philadelphia to the Limbo Lounge. My interest in archiving being known to a handful of colleagues eager to deaccession their own cardboard boxes, I found I had enough material to create “wallpaper” for an entire floor of the exhibition, in which scanned announcements for gallery shows 20 years before provided the backdrop for a sub-exhibition of photographic portraits of East Village artists.

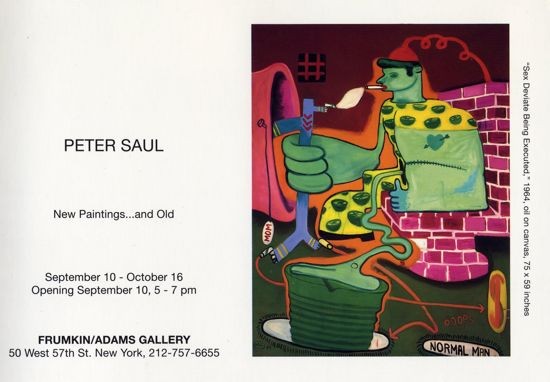

Then in 2008 I was invited by the Orange County Museum of Art to organize a 50-year retrospective of Peter Saul. This was the culmination of a lifelong desire of mine to reposition Saul in the context of recent developments in American art, which in turn propel him from the sidelines to the forefront. Having been an outspoken Saul fan since my earliest days, I discovered when I consulted the Image Archive that I not only had dozens of cards, but also an abundance of catalogs, articles, checklists and notes from the artist over the years, as well as an accumulation of photographs, slides and transparencies. In fact, on our first day sitting down to work on the exhibition together, Saul acknowledged that, on the level of sheer visual documentation, I possessed a more thorough record of his career than he did.

In recent years, I’ve decided to become more public about my collection, especially now that it’s clear that this is something the digital revolution can never co-opt. I now explain to young curators that until they establish their own working archive, they’re essentially flailing about among the vicissitudes of their own memories, which becomes a problem once they’re active for more than 10 years. Similar to artworks themselves, archives of historical ephemera are not simply useful research tools for the people who study art in its time; they gradually become repositories for future historians seeking, for example, a sense of how the art world of the late 20th century/early 21st century – during the time of its greatest expansion in history to date – appeared to those who worked inside its precincts.

I continue to refer to it as a collection, however, because the Image Archive seems to occupy a middle zone between the unmediated artwork in isolation, and the hyper-mediated absorption of digital information in a database that has no beginning or end.