100 years of art in the Japanese archipelago—In the 100th year since the Great Kanto Earthquake and the birth of Hachiko

The current statue of Hachiko outside Shibuya Station, Tokyo.

The current statue of Hachiko outside Shibuya Station, Tokyo.

On September 16, I attended “Kazushi Ooura: Mt. Unzen Fugen/Strata of Memory” at the Musashino Art University Museum & Library. At the request of the artist, I had written an article for the exhibition catalogue and was due to take part in a public talk scheduled for that day. I commented in the catalogue on Ooura’s efforts in visiting the site of the Mount Unzen-Fugen disaster more than 50 times over a period of 30+ years beginning in 1992 and continuing to create work on the subject, so I will not repeat myself here. It was while staying in Shimabara last year as part of the preparations for the exhibition “UNZEN—The Heisei Eruption: through Sunamori Katsumi and Mitsuyuki Toyohito” (2022) organized by the Institute for Art Anthropology, Tama Art University, and supervised by myself, that I learned of Ooura’s activities.

“Kazushi Ooura: Mt. Unzen Fugen/Strata of Memory,” installation view, Musashino Art University Museum & Library, Tokyo, 2023. Photo Ken Kato.

“Kazushi Ooura: Mt. Unzen Fugen/Strata of Memory,” installation view, Musashino Art University Museum & Library, Tokyo, 2023. Photo Ken Kato.

“UNZEN—The Heisei Eruption: through Sunamori Katsumi and Mitsuyuki Toyohito,” installation view, Tama Art University Art-Theque Gallery, Tokyo, 2022. Photo Yusuke Tsuchida, courtesy Tama Art University Institute for Art Anthropology.

“UNZEN—The Heisei Eruption: through Sunamori Katsumi and Mitsuyuki Toyohito,” installation view, Tama Art University Art-Theque Gallery, Tokyo, 2022. Photo Yusuke Tsuchida, courtesy Tama Art University Institute for Art Anthropology.

In fact, it was also at Shimabara that Ooura first learned of our activities, and it seems extraordinary that our respective initiatives became entangled on the Shimabara Peninsula 30 years after the large-scale pyroclastic flows at Mount Unzen-Fugen, and that our exhibitions were held at art universities in Tokyo in 2022 and 2023. Moreover, the openings of both shows took place on anniversaries of large-scale pyroclastic flows that occurred at Mount Unzen-Fugen in 1992 (the “UNZEN” exhibition at Tama Art University opened on June 3, the “day of prayer”), while the above-mentioned talk was also timed to coincide with the anniversary of a large-scale pyroclastic flow the same year (September 15, though the actual talk was held the following day, a Saturday).

I wrote in detail about creative activities focusing on eruptions of Mount Unzen-Fugen previously when I featured in this column the work of photographer Katsumi Sunamori (see Notes on Art and Current Events 89-91). Following this, however, the world was swept up in the COVID-19 pandemic, and to be honest I did not imagine that now, when that disaster has at last eased, I would be meeting Mount Unzen-Fugen again in earnest through the work of a different artist. From Katsumi Sunamori to Kazushi Ooura via Toyohito Mitsuyuki. All three were strangers of which my former self had no knowledge whatsoever. One could even say I am being led to them by Mount Unzen-Fugen. Perhaps in these volcanic activities there is some important meaning still hidden to me.

Incidentally, there is another reason why I mentioned my talk with Ooura at the beginning of this column. On the day of the talk, another exhibition titled “Kiyoji Otsuji: Seeing Beyond Things—Towards a New Perspective on Photography Archives” was also being held at Musashino Art University to mark the 100th anniversary of Otsuji’s birth. Naturally, I was greatly interested in this show about a photographer who was once a member of Jikken Kobo/Experimental Workshop, a group made up of artists who came together in the spirit of “experimentation” advocated by Shuzo Takiguchi, and who had a major influence on those who followed. But in fact the first things that attracted my attention at the entrance to the venue were the words “100th anniversary.”

“Kiyoji Otsuji: Seeing Beyond Things—Towards a New Perspective on Photography Archives,” installation view, Musashino Art University Museum & Library, Tokyo, 2023. Photo Yasuo Saji.

“Kiyoji Otsuji: Seeing Beyond Things—Towards a New Perspective on Photography Archives,” installation view, Musashino Art University Museum & Library, Tokyo, 2023. Photo Yasuo Saji.

The figure “100” has special meaning for people who think about earthquakes. Needless to say, this is because September 1, 2023 (Disaster Prevention Day) marks exactly 100 years since the Great Kanto Earthquake, which among all the great disasters that have struck the Japanese archipelago in the modern era remains unparalleled in terms of the enormous damage it caused in the capital, Tokyo. From around the end of summer, the mass media, too, turned their attention to this great earthquake, putting together special issues and other reports that attracted interest from many quarters. And while I have no intention at all of belittling the importance of these reports, in many cases there was no improvement in the way they dealt with the disaster, and to be honest, from the standpoint of art criticism, I felt they could have benefitted from the inclusion of slightly different perspectives. It was partly because of this that I became particularly sensitive to the figure “100” this year. And so it was that at the above-mentioned Otsuji exhibition, I noticed the figure “100” before anything else.

The first thing I took from this show was the fact that 2023 being the 100th anniversary of Kiyoji Otsuji’s birth meant that he was born in the year of the Great Kanto Earthquake. And, that I had not previously thought about such things. According to the chronological record of Otsuji’s career, he was born on July 27, 1923, in Ojimamachi, Minami Katsushika-gun, Tokyo (now Ojima, Koto Ward). In other words, it was just a month and a bit after he was born that the Great Kanto Earthquake struck. Moreover, he was born in the low-lying area of eastern Tokyo near Tokyo Bay that suffered devastating damage in the quake. Koto Ward experienced particularly severe damage. I immediately tried to imagine what kind of misfortune Otsuji experienced. Since he had just been born, it is unlikely that he had any memories of the disaster. However, this does not change the fact that he grew up as the reconstruction effort was at last getting underway and a completely new “Tokyo” was beginning to take shape. What kind of shadow did these memories cast over the formation of Otsuji the photographer? This is the kind of thing I want to think about in the context of the Great Kanto Earthquake.

Related to this, there is a surprisingly large number of exhibitions this year with the words “100th anniversary” in their title. The first I want to mention is “100th anniversary of the Birth of Yamashita Kiyoshi, a Retrospective” (Sompo Museum of Art). Yamashita was actually born on March 10, 1922, the year before the Great Kanto Earthquake, so accurately speaking the 100th anniversary of his birth was last year, but the important thing is that the one-year-old Kiyoshi and his family were living in Tanakamachi, Asakusa Ward (now Nihonzutsumi, Taito Ward) in Tokyo in September 1923, which like all of the low-lying area of eastern Tokyo near Tokyo Bay suffered severe damage. In fact, the whole of Tanakamachi was destroyed and the Yamashitas, having lost their home, moved to Kiyoshi’s parents’ hometown of Niigata. This was as autumn was turning into winter. For people of that period, the difference between the climate in Tokyo and the climate in Niigata was almost intolerable. A short time later Yamashita became extremely ill and his inability to adapt to his surroundings due to his stuttering and his developmental disability bore fruit in a different form through the hari-e collages he began making at the Yawata Gakuen facility for children needing special care. So there is an inseparable connection at the most basic level between the Great Kanto Earthquake and Kiyoshi Yamashita’s hari-e. When it comes to earthquakes, my interest is also focused on these kinds of things.

On the subject of the Great Kanto Earthquake and art, the day the quake struck, September 1, was a preview day at both the revived Inten Exhibition and the Nika Exhibition. After the venue in Ueno was damaged in the quake, the opening of the shows to the public scheduled for the following day was cancelled and the autumn Teiten Exhibition was also called off. Large-scale, government-sponsored exhibitions have only been canceled twice, in 1923 and the year Japan was defeated in the war. Such things are a kind of historical fact. Some artists died in the Great Kanto Earthquake while a considerable number of artworks were also no doubt damaged or destroyed by fire. As is well known in the art world, a number of new or avant-garde art movements, including Mavo, emerged around the time of the quake.

This time, however, the event I want to address as a problem in art by way of the “100th anniversary” of the Great Kanto Earthquake with a detour through criticism is the “Hachiko’s 100th Birthday Celebration” exhibition at the Shibuya Folk and Literary Shirane Memorial Museum. The statue of Hachiko outside Shibuya Station, one of Tokyo’s largest, has an exit named after it (Hachiko Exit) and stands in front of Shibuya’s famous scramble crossing (it also appears to shoulder behind it and to its left Taro Okamoto’s mural The Myth of Tomorrow). It depicts what is probably one of the best-known pet dogs in the world, and in this sense this bronze statue has a significance that cannot be ignored when thinking about art in Japan over the last 100 years since the dawn of modernity, a century in which Kiyoji Otsuji, Kiyoshi Yamashita and Hachiko became entangled through art. This is the only way I can think about it.

However, there are also many arguments and anecdotes concerning this famous dog. These include his appropriation for the purposes of patriotic/feudalistic moral education on account of his “loyalty” and the theory that he went to the station everyday not to meet his master, but out of a desire for yakitori from a nearby store. Here, however, rather than commenting on the rights and wrongs or truth and falsehood of these arguments and anecdotes, I would like to focus on and consider how it is through none other than a bronze statue that we know so much today about Hachiko’s existence.

Hachiko in his later years. Shibuya Folk and Literary Shirane Memorial Museum.

Hachiko in his later years. Shibuya Folk and Literary Shirane Memorial Museum.

But why was it that Hachiko was turned into a statue in the first place? These days, the statue of Hachiko, which is a famous meeting place at Shibuya Station and constantly surrounded by people taking commemorative photos, is not received as an “artwork,” and in fact if one were to “appreciate” it without moving in what is probably one of the most crowded places in Japan one would undoubtedly be treated like a crank. But the statue of Hachiko is unmistakably a work of sculpture before it is a meeting place, and so of course there is an artist who made it. Having said that, the statue of Hachiko that stands in front of Shibuya Station today is in fact the second such work, the first having been made before the war. The name of the man responsible for creating that first statue is Teru Ando. It was unveiled during a grand ceremony at Shibuya Station on April 21, 1934, which perhaps uncoincidentally was the Year of the Dog according to the Chinese zodiac.

I will touch on the particulars of this later, but first we need to consider why a bronze statue of a pet dog was made in the first place. Normally, when it comes to public sculpture, bronze statues are made to recognize figures who have achieved great deeds of historical importance. Though one could understand it if it were an idol or imaginary animal or, for the sake of argument, a popular character celebrated in the media, one cannot deny that regardless of how “loyal” he was, for a bronze statue of an Akita dog who was originally just a pet to become the symbol of a major station in Tokyo gives a strange impression. However, in order to get to the core of the statue of Hachiko, we need to start by recapturing this strange impression. If you are hesitant about visiting the site itself, a photograph is adequate. I want you to take your time and carefully observe and appreciate this statue. One could understand it if it were a statue of a person, but regardless of how closely one looks at it, this is a statue of a pet dog, and there is nothing to suggest recognition of character or great achievements (to begin with, it is not a person). In other words, though it goes without saying, a likeness of a pet dog is only a likeness of a pet dog, and the more one looks at it the more one senses from the statue of Hachiko the undeniable fact that someone has simply “tried to turn a pet dog into a bronze statue.”

By continuing to stare fixedly at it, “tried to turn a pet dog into a bronze statue” becomes “turned a pet dog into a bronze statue.” If one can continue looking at the statue of Hachiko until this happens, then at this point the statue of Hachiko will surely have completely shed any special meaning that might be included in parentheses, such as “faithful dog.” And it will take on the appearance of a readymade “statue of a pet dog.” In fact, for a while after the statue of Hachiko’s unveiling, apparently some people were under the strange impression that a random pet dog had been turned into a statue and given a seat of honor in front of the station. But when one thinks about it, this too is not surprising. Just as these days we do not harbor any particular suspicions when we hear the words “bijutsu,” meaning “art,” or the English loanword “āto” (though I continue to feel a slight sense of antipathy resistance whenever I use the latter), it is simply that the sense of discomfort that was probably widely shared in the beginning has been forgotten. What I am saying is that here, we need to discuss and view the statue of Hachiko after restoring the suspicions, antipathy and sense of discomfort that existed in the beginning. And now that we have restored the statue of Hachiko phenomenologically (?), let us return to the story of the statue’s maker. This is also the story of why a pet dog that was nothing but a single Akita dog came to be “turned” into a statue in the first place.

As hinted at above when I repeatedly emphasized the number “100,” Hachiko was born on November 10, 1923, soon after the capital was struck by the Great Kanto Earthquake, in the village of Niida in Kita-Akita (now Odate), Akita. On January 14 the following year (1924), he was sent to the residence (in Shibuya-cho, Toyotama-gun [now Shoto in Shibuya Ward], Tokyo) of his new owner, Hidesaburo Ueno, who worked as a professor at the Faculty of Agriculture at the Tokyo Imperial University. Compared to the low-lying area of eastern Tokyo near Tokyo Bay, the Shibuya area was relatively unaffected by the earthquake, but the capital had still only just set out on the road to recovery. For Ueno, who was anxious about his health to begin with, bringing a new Akita dog into his home after the earthquake was probably important as a source of comfort. Here, too, the Great Kanto Earthquake may have made some invisible contribution in terms of Hachiko coming to Tokyo. However, the year after Ueno became Hachiko’s owner, he suddenly died. Despite this, Hachiko, who had already become attached to Ueno and had got into the habit of heading over to Shibuya Station, maintained this routine for a long time even after Ueno’s death, as if waiting for his return.

Hachiko, who was initially the subject of violent attacks and mischievous pranks, suddenly became famous in 1932, quite a while after Ueno’s death, when a letter to the editor of the Asahi Shimbun was turned into an article under the headline, “A tale of affection and an old dog: Seven long years waiting for his dead master to return” (Tokyo Morning Edition, October 4, 1932). This article had a dramatic effect, so much so that not only did the cruel treatment Hachiko experienced at Shibuya Station cease, but he came to be widely adored as an exemplar of pet dogs. This popularity continued until eventually a plaster statue of Hachiko titled Japanese dog was showed at the Teiten Exhibition in October 1933. The maker was the above-mentioned Teru Ando, who had studied sculpture at the Tokyo Fine Arts School. (The following account is based on notes I took while viewing “Hachiko’s 100th Birthday Celebration.” Given there was no catalogue produced to accompany this exhibition and that photography was prohibited, I made these notes on the spot in pencil based on multiple captions.) (1)

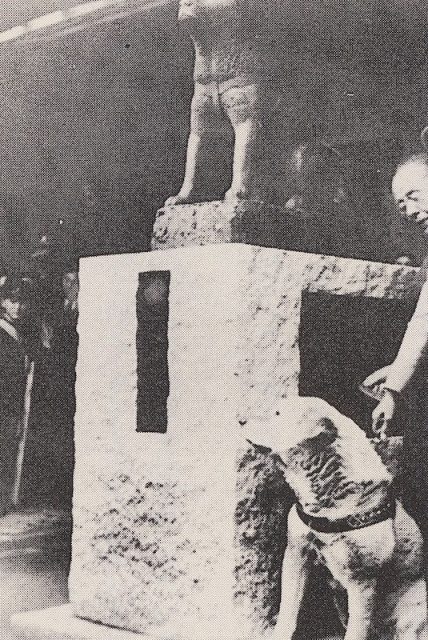

Hirokichi Saito, the first president of the Association for the Preservation of the Japanese Dog, who worked tirelessly to inform the public about Hachiko, was also a graduate of the Tokyo Fine Arts School and had a good understanding of art. The plaster statue of Hachiko that Ando produced with Saito’s assistance received great acclaim, and with Hachiko’s fame spreading, that same year it was suggested that a wooden statue of Hachiko be produced and fundraising immediately got underway. However, the artist whose name was mentioned at this time was not Ando, but another sculptor, Seiho Ouchi. Ouchi showed an interest in the job and even went as far as producing original drawings for a woodblock postcard of Hachiko to assist in realizing a wooden statue, but in the end it was a bronze statue by Teru Ando that came to be produced. Ando (b. 1892), who studied sculpture at the same Tokyo Fine Arts School as Ouchi (b. 1898), who had studied there under Koun Takamura and was also a sculptor of Buddhist images, first entered Waseda University, as a result of which his entry into the Tokyo Fine Arts School was delayed. For this reason, the two men ended up being contemporaries, and as they represented the two great strands of sculpture in the form of woodcarving and bronze statuary, they had a strong sense of rivalry. Both Saito and Ando called for a halt in fundraising activities for the creation of a wooden statue of Hachiko, and so it was that a more permanent bronze statue came to be made. Fundraising for this new statue began in 1934, and on March 10 the same year 3000 people attended a “Hachiko evening” at the Nippon Seinenkan Hall. Momentum gathered quickly, and on April 21, 1934, two events, a ceremony and the unveiling of the first statue of Hachiko, were held on a grand scale at separate locations at Shibuya Station. In other words, unusually for a bronze statue, the statue of Hachiko was completed and unveiled while Hachiko himself was still alive. (In fact, there are photos of Hachiko looking up at his own statue.)

Hachiko looking up at his own bronze statue. Source: Hachikō bunken-shū, ed. Masaharu Hayashi, 1991.

Hachiko looking up at his own bronze statue. Source: Hachikō bunken-shū, ed. Masaharu Hayashi, 1991.

But that is not all. Separate from the statue of Hachiko installed at Shibuya Station, small reclining statues of Hachiko (bronze) were made by Ando and presented to the Imperial Family. Ando made three of these statues for the Empress Dowager (Empress Teimei, the wife of Emperor Taisho and mother of Emperor Showa), who became interested in Hachiko after reading the above-mentioned newspaper article and wanted to meet him (the meeting proved difficult and was never realized), which were presented to the Emperor, the Empress and the Empress Dowager. However, because there are differences in the shapes of bronze statues, despite being from the same mold, in fact up to around ten of these small statues were made, the three best of which were apparently gifted to the Imperial Family. It is said that the remaining statues were given to Ando’s acquaintances, though one is in the possession of a museum in Kagoshima Prefecture, the home prefecture of Ando and the Ando family.

Display at “Hachiko’s 100th Birthday Celebration,” Shibuya Folk and Literary Shirane Memorial Museum, Tokyo, 2023. Center: Teru Ando’s bronze Reclining figure of the faithful dog Hachiko, minus parts destroyed in the war. Right: Seiho Ouchi, The faithful dog Hachiko, iron. All photos hereafter: ART iT.

Display at “Hachiko’s 100th Birthday Celebration,” Shibuya Folk and Literary Shirane Memorial Museum, Tokyo, 2023. Center: Teru Ando’s bronze Reclining figure of the faithful dog Hachiko, minus parts destroyed in the war. Right: Seiho Ouchi, The faithful dog Hachiko, iron. All photos hereafter: ART iT.

Also on display at “Hachiko’s 100th Birthday Celebration” was an iron statue of Hachiko (February 1935) thought to have been made by Ouchi, whose spirit of rivalry was no doubt piqued when, subsequent to the loss of impetus for a wooden statue, Ando’s bronze statues were presented to the Imperial Family. However, though also a reclining figure, the fact that in Ouchi’s statue the left and right are reversed does give the impression of some animosity on Ouchi’s part. In any event, the fact that around the time that the first statue of Hachiko was installed at Shibuya Station, the reputation of this pet dog had reached as far as the Imperial Family, resulting in three bronze statues being presented to them, seems astonishing.

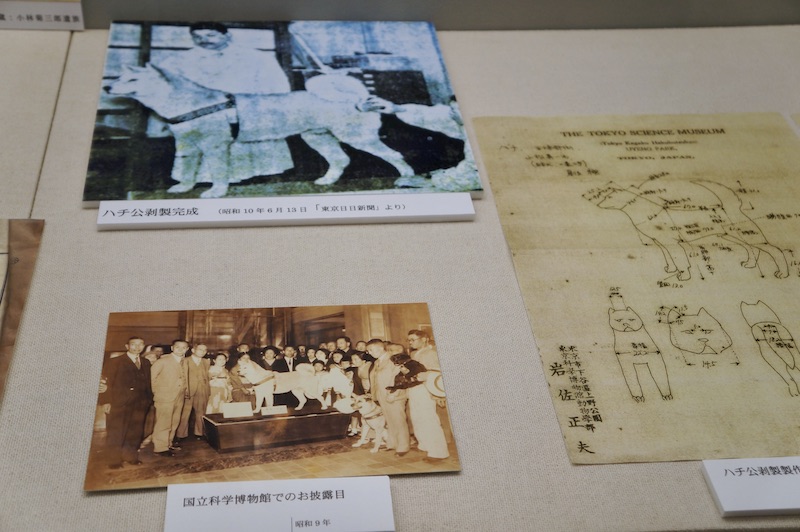

Meanwhile, Hachiko, who had been turned into a statue when he was still alive, was now dead. On March 8, 1935, the year after his statue was unveiled, the body of Hachiko was found in the vicinity of Inari Bridge near Shibuya Station (now a part of Shibuya Stream). The cause of death is now presumed to be cancer, which had spread throughout his body. Hachiko was mounted soon afterwards and the results presented to the public on June 15, 1935. Hachiko’s taxidermy can still be viewed at the National Museum of Nature and Science. Kiichi Sakamoto, who together with Shin Honda was responsible for the taxidermy, introduced the latest taxidermy techniques, which involved using plaster to make an armature inside the animal’s body where previously sawdust had been used and fitting Hachiko’s skin over the top of this. Hence the results were more realistic than expected, almost as if Hachiko had been brought back to life.

Display describing Hachiko’s taxidermy at “Hachiko’s 100th Birthday Celebration.”

Display describing Hachiko’s taxidermy at “Hachiko’s 100th Birthday Celebration.”

However, Japan was about to plunge into war. With the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War and later, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Pacific War, within a few years Japan began experiencing a shortage of materials, and ultimately a system of obligatory supplies of goods to the government was introduced. This system was designed to ensure the continuation of the Great East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere by prioritizing the supply of metals, precious stones and other goods to the government, and because bells and bronze statues from all around the country were also appropriated for military use, these items disappeared one after another. The popular statue of Hachiko was no exception (after all, he was a faithful dog). However, as a result of Hirokichi Saito’s strenuous efforts, the statue of Hachiko was saved on the grounds of artistic merit, and in a farewell ceremony on October 12, 1944, the year before the war ended, it was removed. The following day, underneath the headline, “Statue of faithful dog Hachiko goes into battle,” the Yomiuri Shimbun announced that “Hachiko had departed for military service with the Japanese flag draped around his neck.” The removed statue was meant to have been stored in a secret location. But in the chaos that reined just before the end of the war, this first statue of Hachiko was sent to a factory in Hamamatsu and melted down. Later, the Hokuriku Chunichi Shimbun (March 7, 2015) reported that the statue of Hachiko “was turned into parts for locomotives running on the Tokaido Line.” (2)

So, how did the statue of Hachiko that currently stands in front of Shibuya Station (the second statue of Hachiko) come to be made? According to the explanation at the “Hachiko’s 100th Birthday Celebration” exhibition, there is a theory that talk of creating a second statue arose after the war in response to a desire among foreigners to see the “faithful dog” statue whose fame had spread overseas. However, it is also possible that supporters, who found it difficult to start an active reconstruction movement given that from a Japanese point of view the statue was linked to the enhancement of national prestige, thought that treating the idea as having originated from the victorious nations would make it easier to build momentum. In fact, it seems that the plan to reconstruct the statue of Hachiko was initially brought up at the request of GHQ and promoted as a symbol of the post-war reconstruction. However, the studio owned by Teru Ando, who created the first statue of Hachiko and was familiar with the production process, was destroyed by fire in a US air raid on May 25, 1945, and Ando himself was killed. (One of the reclining statues made as gifts to the Imperial Family that was stored at Ando’s house also partly melted in the air raid.)

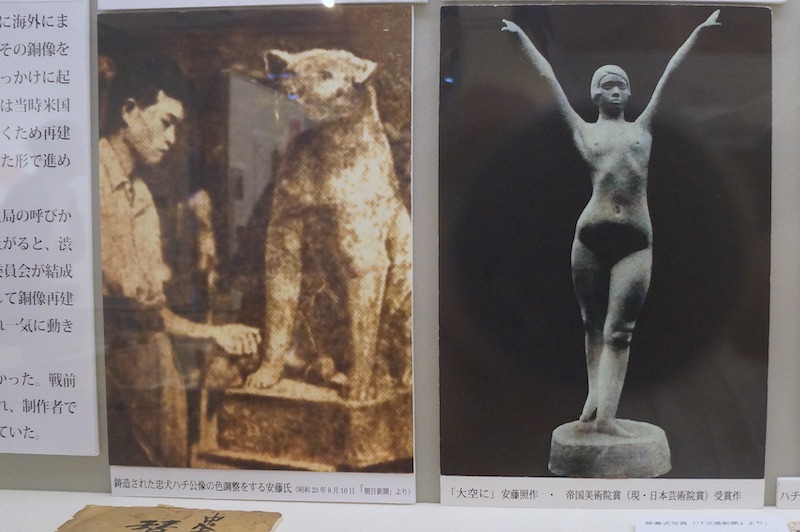

With both the artist and his studio lost and no model in existence, reconstructing the statue of Hachiko was not easy. It was at this point that Ando’s eldest son, Takeshi, came forward. In keeping with the “100th anniversary” theme of this column, Takeshi, who like his father studied sculpture at the Tokyo Fine Arts School, was born in 1923, the year of the Great Kanto Earthquake, and moreover in Shibuya, making him a perfect candidate for the job. Having observed his father’s process in creating the first statue of Hachiko, Takeshi began by making a plaster image with the cooperation of Hirokichi Saito. (The plaster prototype created at this time is in the possession of Tsuruoka City in Yamagata Prefecture, and displayed for a limited time at JR Tsuruoka Station. Incidentally, present-day Tsuruoka is where Saito was born.) However, the biggest problem was acquiring bronze due to the shortage of materials in the period immediately after Japan’s defeat. Takeshi solved this by “requisitioning” and melting down Ozora ni (To the sky), a statue of a nude woman his father made that won the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts Award, begging the old man’s forgiveness for doing so. And so it was that Teru Ando’s statue of a nude woman was turned into the second statue of Hachiko, which was unveiled on August 15, 1948, the anniversary of the end of the war (and the Obon festival).

Display related to reconstructing the statue of Hachiko (the second statue of Hachiko) in “Hachiko’s 100th Birthday Celebration.” Left: Takeshi, the son of Teru Ando, who created the first statue of Hachiko. Right : Teru Ando’s Ozora ni (To the sky), which was melted down to create the second statue of Hachiko.

Display related to reconstructing the statue of Hachiko (the second statue of Hachiko) in “Hachiko’s 100th Birthday Celebration.” Left: Takeshi, the son of Teru Ando, who created the first statue of Hachiko. Right : Teru Ando’s Ozora ni (To the sky), which was melted down to create the second statue of Hachiko.

In this way, between the real Hachiko and the statue of Hachiko, there are numerous “repetitions” concerning originality (or, to follow the example of Rosalind E. Krauss, there is “originality and repetition” concerning the statue of Hachiko). This had already begun with the compositional arrangement in which the living Hachiko looked up at the statue of Hachiko that would later become more famous than him while being a representation of himself. Around this period, Hachiko became the subject of newspaper articles, was turned into plaster statues, featured on postcards, was the subject of discussions around the creation of a wooden sculpture, was turned into a bronze statue, and was turned into small bronze statues that were presented to the Imperial Family, around ten of which were made from the same mold and scattered around the country, some of which survive and others of which were damaged or lost. An iron statue was made by a rival sculptor, and Hachiko was also turned into a taxidermy mount using the latest techniques. When war broke out, the statue of Hachiko became the subject of the obligatory supply of goods to the government and was melted down and turned into parts for locomotives running on the Tokaido Line. Then, in order to produce a replacement statue, another plaster image was made and eventually another bronze statue was completed by melting down a statue of a nude woman left behind by the sculptor’s own father. As well, there are numerous variations of the statue of Hachiko, with images of the dog existing in Tsu, Mie Prefecture, the birthplace of Hachiko’s owner, Hidesaburo Ueno; on the Hongo campus of the University of Tokyo where Ueno worked; in Odate, Akita where Hachiko was born; in Tsuruoka, Yamagata; and overseas in the US states of New Jersey and Rhode Island, and in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. There is also Hachi: A Dog’s Tale (2009), a Hollywood remake of the Japanese movie Hachiko Monogatari (1987) starring Richard Gere (incidentally, this year, a Chinese remake was also released), as well as ceramics, records and other Hachiko-related merchandise. And at the entrance to “Hachiko’s 100th Birthday Celebration” there stood a large statue of Hachiko that appeared to have been made from FRP.

Entrance to “Hachiko’s 100th Birthday Celebration” at the Shibuya Folk and Literary Shirane Memorial Museum.

Entrance to “Hachiko’s 100th Birthday Celebration” at the Shibuya Folk and Literary Shirane Memorial Museum.

As long as the statue of Hachiko is an “image,” such transformations and repetitions are unavoidable. A melted down statue of Hachiko being turned into parts that run (like a dog?) along the Tokaido Line, and a nude statue becoming the second statue of Hachiko that has been stroked by countless unsuspecting visitors are just two examples of these unavoidable changes in image and energy. One is reminded of how Joseph Beuys melted down various materials, using the propensity of matter to dissolve from solid into liquid to turn them into completely different images, and extracting symbolic energy from matter by way of this transformative process.

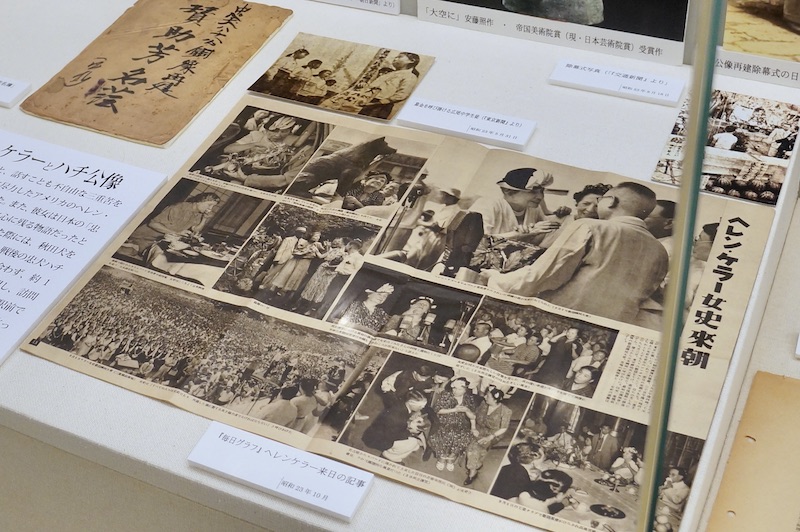

Display at “Hachiko’s 100th Birthday Celebration” of photos in Mainichi Graph (October 1948) documenting Helen Keller’s Japan visit, including one of her touching the statue of Hachiko.

Display at “Hachiko’s 100th Birthday Celebration” of photos in Mainichi Graph (October 1948) documenting Helen Keller’s Japan visit, including one of her touching the statue of Hachiko.

Given all this, it seems to me that confirming the existence of the statue of Hachiko by touching it with one’s hands, as Helen Keller did, rather than discerning it with one’s eyes is the way to grasp the essence behind its invisible variations. In September 1948, shortly after the second statue of Hachiko was unveiled, Helen Keller, who was visiting Japan and was already a fan of Hachiko, confirmed its existence by touching it with her hands due to her deafblindness. Its texture was neither that of a dog as an image nor that of a bronze statue as a memorial. At this moment, Hachiko had been reduced to the sense of touch itself. But is this itself not the most concrete image we can freely imagine of the incorporeal Hachiko? In fact, many people hurriedly approach the statue of Hachiko in front of Shibuya Station and touch the parts of the legs that are within reach without discerning the whole with their eyes. Which is why these parts of the legs of the current statue are shinier than the body. It is in this very shininess or smoothness that we see, or rather feel, the essence of the statue of Hachiko.

Postscript 1: In the flyer for “Hachiko’s 100th Birthday Celebration,” the words “We will tell the real story of Hachiko” caught my eye. In fact, as suggested by the passage, “While the story of Hachiko is widely known, things contrary to the facts are also widely known due to the dissemination of false information including speculation and lies. This year, the 100th anniversary of Hachiko’s birth, we will reveal information that is as accurate and detailed as possible and share details of the actual life of Hachiko and of the people who knew him.” (from the exhibition website), as a current exhibition concerning Hachiko, “Hachiko’s 100th Birthday Celebration” reflects the latest information and the results of investigations conducted by the museum. As well as presenting previously unreleased photos of Hachiko, the exhibition also screened as a related event Hachiko Monogatari, a rare 16mm black-and-white film made in 1958.

Postscript 2: In 2020, Yasuhiro Suzuki’s Shibuya Hachi Compass was installed as a permanent public artwork in Miyashita Park near Shibuya Station.

1.Also consulted: Makoto Shigeno, ”’Innen’ no futatsu no Hachikō zō ga 80-nen no toki o hete deau” [Two “fated” Hachiko statues meet after 80 years], Shibuya Bunka Project, May 26, 2015 (last accessed September 19, 2023).

2. Hajime Mizoguchi, “Chūken Hachikō, gun’yō dōbutsu to senji taisei—dōbutsu bunka-shi no shiten kara” [The faithful dog Hachiko, military animals and the wartime regime: from the perspective of animal cultural history], Kagakushi kenkyū 285 (April 2018),((last accessed September 19, 2023).

- “Hachiko’s 100th Birthday Celebration” was held from August 22 through October 9, 2023, at the Shibuya Folk and Literary Shirane Memorial Museum, Tokyo.

- “Kazushi Ooura: Mt. Unzen Fugen/Strata of Memory” and “Kiyoji Otsuji: Seeing Beyond Things—Towards a New Perspective on Photography Archives” were held from September 4 through October 1, 2023, at the Musashino Art University Museum & Library.

- “100th anniversary of the Birth of Yamashita Kiyoshi, a Retrospective” was held from June 24 through September 10, 2023, at the Sompo Museum of Art, Tokyo.