“Smallness” and “largeness” – On Tatsuo Kawaguchi’s “relations”

Installation view of “Tatsuo Kawaguchi: Relation” at Shigeru Yokota Gallery, Tokyo, 2022. ©︎Tatsuo Kawaguchi, courtesy Shigeru Yokota Gallery.

Installation view of “Tatsuo Kawaguchi: Relation” at Shigeru Yokota Gallery, Tokyo, 2022. ©︎Tatsuo Kawaguchi, courtesy Shigeru Yokota Gallery.

I’ve recently had the opportunity to view in succession a number of old and new works by Tatsuo Kawaguchi. Specifically: the solo exhibitions “Relation” at Shigeru Yokota Gallery and “Relation – Seed / Copper” at SNOW Contemporary, and at Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale 2022, postponed a year due to Covid-19, the new work Time of Farm Tools (2022) along with Relation – Blackboard Classroom (2003) and Art Drawers (2012). I will comment on these later as the occasion demands, but first I would like to offer some thoughts on what it is Kawaguchi is trying to bring into to this world through these and other works.

Installation view of “Tatsuo Kawaguchi: Relation – Seed / Copper” at SNOW Contemporary, Tokyo, 2022. Photo: Keizo Kioku, ©︎Tatsuo Kawaguchi, courtesy SNOW Contemporary.

Installation view of “Tatsuo Kawaguchi: Relation – Seed / Copper” at SNOW Contemporary, Tokyo, 2022. Photo: Keizo Kioku, ©︎Tatsuo Kawaguchi, courtesy SNOW Contemporary.

Tatsuo Kawaguchi and Relation – Blackboard Classroom (2003), Matsudai Nobutai, Tokamachi, Niigata. ©︎Tatsuo Kawaguchi, courtesy Shigeru Yokota Gallery, Tokyo.

Tatsuo Kawaguchi and Relation – Blackboard Classroom (2003), Matsudai Nobutai, Tokamachi, Niigata. ©︎Tatsuo Kawaguchi, courtesy Shigeru Yokota Gallery, Tokyo.

The first thing one notices is that most of these solo exhibitions and works are titled “Relation.” Of course, this is an all too obvious premise when it comes to discussing Tatsuo Kawaguchi, but depending on what approach I as a critic adopt to this all too obvious fact, one’s subsequent interpretation of Kawaguchi’s works changes completely. Accordingly, to discuss these individual works without mentioning it would itself amount to a lack foresight as to where these words are being directed. It is for these reasons that I am about to embark on a lengthy, abstract discussion divorced from the actual works.

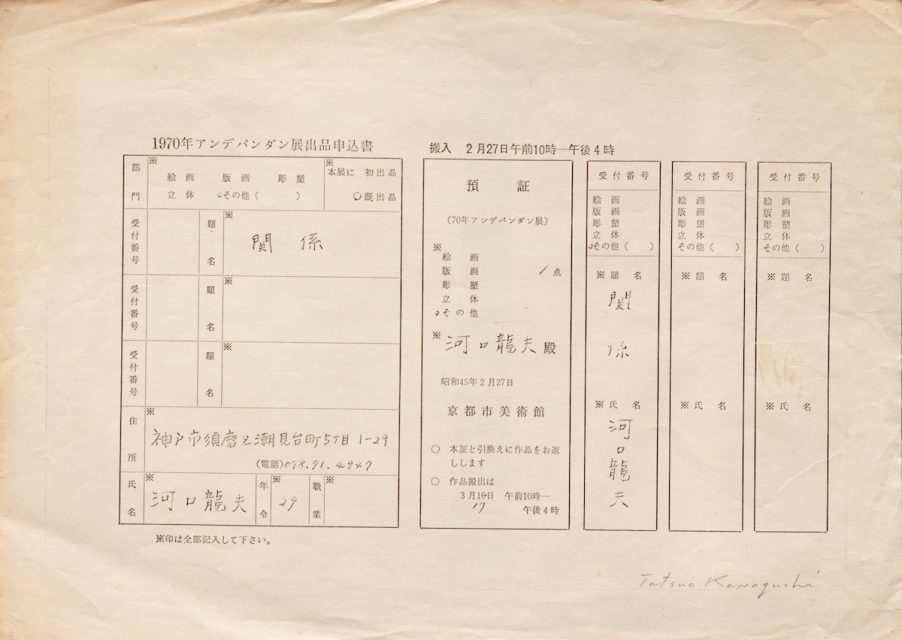

The word “relation” first appeared in the titles of Kawaguchi’s works in the series “Relation,” “Relation – Heat” and “Relation – Light” unveiled in 1970. That the first of these series, “Relation,” concerned the state of “exhibitions” is of great interest and closely related to the gist of the second half of this essay.

Relation (1970) ©︎Tatsuo Kawaguchi, courtesy Art Office Ozasa. A project created for the 1970 Independent Exhibition (Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art). A copy of the Kawaguchi’s “application to submit work” was submitted at that point as the “artwork,” and was displayed together with the application, artwork, and exhibition fee receipts as the entire artwork.

Relation (1970) ©︎Tatsuo Kawaguchi, courtesy Art Office Ozasa. A project created for the 1970 Independent Exhibition (Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art). A copy of the Kawaguchi’s “application to submit work” was submitted at that point as the “artwork,” and was displayed together with the application, artwork, and exhibition fee receipts as the entire artwork.

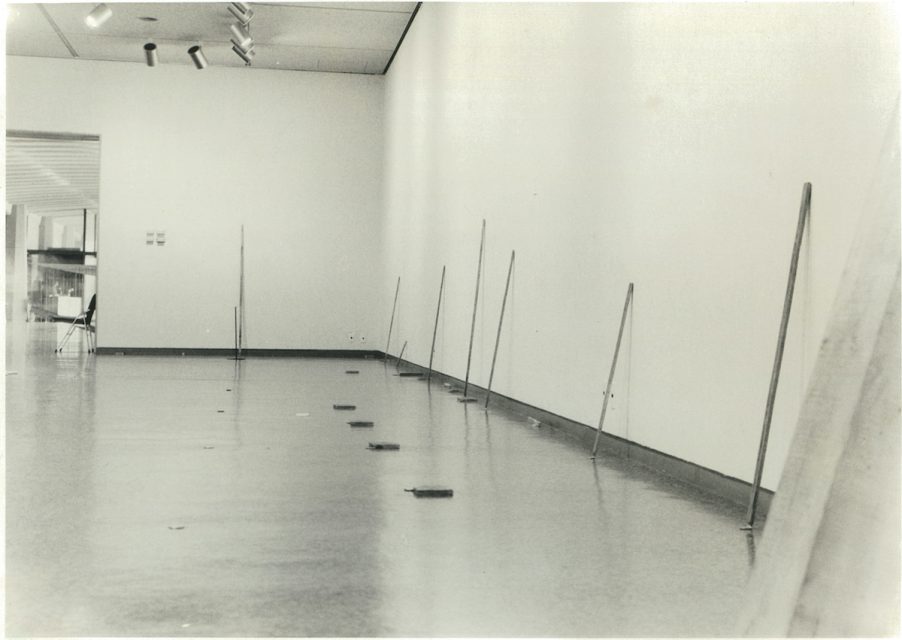

“Relation – Heat” consisted of partially melted lead bars and plates arranged at intervals on the floor or propped up against the gallery walls. At first glance, it calls to mind the work of Mono-ha, whose activities were reaching a peak around this time. If we take presenting sculpturally unprocessed materials in their unaltered state as the initial condition of Mono-ha, then it would not seem odd for these works, too, to be placed in this category. And in fact, changing the form of the materials using heat was not the result of a sculptural choice by the artist. It was largely determined by the physical properties of the raw materials, the artist’s subjective judgment exerting no influence. However, even if this were the starting point, there is an important difference between the activities of the Mono-ha artists and Kawaguchi’s work that cannot be overlooked. By this I am referring to the very concept of “relation.” In the case of “Relation – Heat,” this is clearly expressed through the transmission of heat.

Relation – Heat (1970). Installation view and detail at “August 1970: Aspects of New Japanese Art,” The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, 1970. ©Tatsuo Kawaguchi, courtesy the artist and Shigeru Yokota Gallery.

Relation – Heat (1970). Installation view and detail at “August 1970: Aspects of New Japanese Art,” The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, 1970. ©Tatsuo Kawaguchi, courtesy the artist and Shigeru Yokota Gallery.

What is heat? In physics, this phenomenon is prescribed by the second law of thermodynamics, famous as the source of the concept of entropy. In simple terms, it is an irreversible transfer of energy. In terms of the concept of entropy, transferred energy moves around this universe in accordance with a process that statistically speaking is almost 100 percent unidirectional. For example, blue ink (molecules) dropped into a beaker of water will naturally spread throughout the water over time, but even if the mixture is left to stand the two parts will never return to their original states. Similarly, in “Relation – Heat,” even when cooled, the partially melted lead bars and plates do not return naturally to their original states. In other words, one could say it is a manifestation in the present of a certain amount of time having already passed with respect to the material before our eyes. Which is to say it is also a manifestation of irreversible time. I wrote above that in terms of their initial conditions there were commonalities between Kawaguchi’s work and Mono-ha, but at this point the two are decisively distinguished from one another. As indicated by Lee Ufan when he used the word “encounter” to summarize our engagement with them, in Mono-ha, material objects are interpreted perceptually as nontemporal subjects in accordance with a kind of methodological and phenomenological reduction. Here, transfers of thermal energy or irreversible processes – in short, temporal elements of any kind – are not included.

However, this does not mean we can immediately conclude that it is the presence or absence of the intervention of time with respect to material objects that separates the Mono-ha and Kawaguchi’s work. Time itself is an extremely diverse concept. According to the philosopher Henri Bergson, there exists in this world another kind of time different from the time invoked in physics. For example, to measure time, the first thing we probably think of is a clock, but in fact what a clock measures is nothing more than partitions of space in the form of a clockface (or, in the case of a digital clock, permutations of natural numbers). But within our experiences there certainly exists time of a kind that cannot be measured by the partitioning of space or permutations of natural numbers. Like a dream, for example, where the time the dream experience lasts in minutes on a clock is unrelated to its content. Of course, it is also impossible to establish the kind of context that can be gained from permutations of natural numbers. Accordingly, it is entirely possible to have a dream encompassing several years that lasts just a few minutes when measured with a clock. Or rather, such discontinuous continuity that cannot be reduced to space or permutations is a distinguishing feature of dream time. Then again, even in the case of things experienced in broad daylight after waking from a dream, it is probably a perfectly commonplace and everyday experience for one thing to feel like it takes a long time and another thing to feel like it is over in a flash. Such things are examples of time of the kind that cannot be measured with a clock.

According to Bergson, this is time as memory. Events that are stored as memories undoubtedly arise from physical incidents that occurred at some point in the past. In this sense they have an irreversible quality and, as with the law of entropy, if left alone they will never reverse course and turn back into physical reality. At the same time, however, as touched on above, neither is memory time something that can be measured with a clock. Despite this, memories do not become fixed as memories without some amount of time passing. Accordingly, we can say that there exists after all another kind of time separate from the time measurable with a clock. In art, a certain amount of time is required to view a painting. But this does not mean that someone can determine the minimum amount of time necessary to adequately view a single painting. The time in the first example can be measured with a clock, but the time in the second example cannot. To put it another way, the “encounter” advocated in Mono-ha is engagement with subjects that do not fit into either of the above two categories rendered conscious as the perception of non-temporal entities, as it were. In other words, greater importance is attached to instantaneous awareness cutting across time (recognition) than to memory possessed of a certain breadth (time).

So, given that time has this dual aspect, how can we understand time in the works of Tatsuo Kawaguchi? For my part, I think that when these two aspects of time, despite their different qualities, form some kind of association in the context of the condition of a material object, the differences between the two manifest themselves through that material object, and such a state is called “relation.” In somewhat simplified terms, then, for Kawaguchi, “relation” refers to when physical/spatial time that can be measured with a clock and memory/continuous time that cannot be measured with a clock overlap and stand out based on the state of a material object.

And yet how is it that these two kinds of time can overlap despite the differences in their qualities? Above all, it is because they are both the result of a certain irreversible process. But even if instantaneous awareness and continuous time (memory) overlap, this alone does not mean a basis for this exists. However, just as dreams and reality partially overlap in the course of our daily lives, memory and awareness actually create our everyday and our reality. In terms of “Relation – Heat,” the lead bars and plates have been melted and their nature partially changed due to heat in the context of the passing of physical time, but it is none other than in our memory that we perceive such changes in nature. This is by no means a case simply of lead bars and plates having melted due to heat. It is the irreversible transfer of energy in this universe, and our recognition again in the separate aspect of time that is memory of this absolute loss that can by never be restored. Accordingly – and this metaphor must be used very carefully – “Relation – Heat” somehow takes on the appearance of a grave-post for material objects. But I am saying this not in a figurative sense, because when all is said and done, that thermal energy is never restored once it is transferred equates to death, or put another way, life means the continuation of a process whereby moment by moment living bodies continually resist this irreversible loss of energy. In this sense, “Relation – Heat” boils down to how we understand the existence in this world of the status quo of the transference of thermal energy due to an increase in entropy (heat death) not in terms of physical laws, but in the context of our relationship with memory time. In the final analysis, this means none other than what death is for humans. This is what I meant when I wrote that “Relation – Heat” somehow resembles a grave-post. Conversely, heat is life.

Relation – University Notebooks (2021). ©︎Tatsuo Kawaguchi, courtesy Shigeru Yokota Gallery.

Relation – University Notebooks (2021). ©︎Tatsuo Kawaguchi, courtesy Shigeru Yokota Gallery.

Having said all that, I would at last like to turn to the recent works by Kawaguchi mentioned at the start of this essay. What impressed me most about these works was that school time was inserted as “related,” and as an extension of this, the time of the dead was pushed out as “unrelated.” Of these, the former, which is to say school time, was dealt with specifically in Relation – University Notebooks (2021) presented at Shigeru Yokota Gallery (though one can also consider in relation to this Relation – Blackboard Classroom at the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale). Here, Kawaguchi takes as his material a set of lecture notebooks from his university days (1958-62) that turned up by chance while he was searching for another work, which he stood side by side and inserted sandwich-style between two boards decorated here and there with copper and covered with washi paper. Incidentally, Kawaguchi writes about this work as follows:

Why do I try to be so particular about my notebooks and the education of my university days?

One reason is that education is realized through “relation” between those doing the teaching and those being taught. As one who has long been on the teaching side, it was also a good opportunity to confirm that I was once in the position of being taught. I spent 16 years being educated, made up of six years in elementary school, three years in junior high, three years in high school and four years in university. And I spent from 1962 to 2020 as a teacher. Between 1964 and 1966, I stepped away from teaching to concentrate on my art practice. Deducting those years still means I was involved in education for 56 years. Even I am surprised by that.

[Tatsuo Kawaguchi: Relation, exh. cat. (Tokyo: Shigeru Yokota Gallery, 2022), pp. 12-13.]

It is indeed surprising that Kawaguchi was involved in education for 56 years of his life, but to relate it to what we discussed above, this time is all in the past and at present exists only as memory. By no means will it return to the way it was if left alone. At the same time, the notes Kawaguchi took during the final phase of the 16 years he underwent education were extant as material objects. Of course, the young Kawaguchi receiving his education was no longer present in this world, but he remained as matter and continued to exist in his memory. Kawaguchi engaged with these handwritten notes, which could also be called a physical guarantee of this continuity, as someone who for the next 56 years was involved [in education] from the opposite orientation as teacher, and these two irreversible memory times sandwich the leftover notes from the left and right, forming a “relation” comprising the transference of two different kinds of thermal energy. Incidentally, depending on how one thinks about it, as with the early “Relation – Heat” series touched on above, one could perhaps liken this work to a kind of gravestone. I say this because it is bound together as a “relation” between two separate times via memory, when Kawaguchi was being taught, and when he was teaching, amounting to 16 years and 56 years respectively, times that are different from simple axes of time that can be measured with a clock, such as the past and the time that followed.

To return to the question of why gravestones, it is because for the present Kawaguchi, the Kawaguchi who was being taught is, in a sense, like a dead person. Of course, the present Kawaguchi no doubt still learns from various things. But Kawaguchi the student was different from this. Even though he may learn from various things, this alone does not make him a student. And even if he was to affiliate himself with a school somewhere at his present age, it would likely be as a teacher, not as a student. In this sense, Kawaguchi the student is like a long lost, irretrievable dead person (heat death/unrelated).

In contrast, even though his 56 years of teaching may be in the past, it would be extremely difficult to say that Kawaguchi the teacher is irretrievable. Even if he does not affiliate himself with a school, it is entirely possible that he might stand in front of students in a teaching role in a visiting or invited capacity, and in fact he probably does. In this sense, those lost 56 years represent time that can be easily grafted onto the time the present Kawaguchi is living, which is to say it is none other than time that can be measured with a clock. When viewing Relation – University Notebooks from the perspective of the “relations” concerning the life of an artist that are woven together by these two kinds of time, my answer to Kawaguchi’s question, “Why do I try to be so particular about my notebooks and the education of my university days?” is as follows. It seems that Kawaguchi is concerned with how his self as a living person (physical time, life = heat) can form a relationship with the dead person that is his former student self (memory time = heat death). Kawaguchi, who upon the discovery of the notes his former self wrote between 1956 and 1962 met again by chance through looking at these words his lost self, reacted to them as if they were at once things lost forever that had returned to this world, and a message from a dead person in a different dimension. He likely became interested in exactly how this self as a dead person and other, and his self as a living person, could form a “relation” in this world through material objects.

Installation view of “Tatsuo Kawaguchi: Relation” at Shigeru Yokota Gallery, Tokyo, 2022. ©︎Tatsuo Kawaguchi, courtesy Shigeru Yokota Gallery.

Installation view of “Tatsuo Kawaguchi: Relation” at Shigeru Yokota Gallery, Tokyo, 2022. ©︎Tatsuo Kawaguchi, courtesy Shigeru Yokota Gallery.

In connection with this, I would like to elaborate slightly. To return to the beginning of this essay, the recent solo show at Shigeru Yokota Gallery was itself titled “Relation,” as if touching on the crux of Kawaguchi’s work. At the same time, it is explained at the start of the exhibition catalog that the first step in summoning this title was the exhibition titled “Exhibition” held in 1983, which was the first opportunity Yokota had to collaborate with Kawaguchi in an exhibition. Yokota writes about this as follows:

My collaborations with Tatsuo Kawaguchi, which began with 1983’s “Exhibition,” now number 17. Behind the production of this pamphlet and this latest exhibition is a conversation between the two of us that took place over more than four years, the Covid-19 pandemic emerging therein. This conversation addressed the two questions of the nature of the message of all the works Kawaguchi has created as an artist, and the doubts concerning “exhibitions” he has harbored for many years as someone directly involved.

(Ibid, p. 3.)

Thinking about it on this basis, it occurs to me that there is an aspect of the above-mentioned Relation – University Notebooks that serves as a kind of reply in advance to these questions of Yokota’s. To be precise, I mean the thinking around the nature of “relations” and the nature of “exhibitions” that forms the starting point of Kawaguchi’s practice. In response, after taking the trouble to look up the definition of “exhibition” in the Kojien Japanese dictionary, Kawaguchi states that “Y.S. seems to sense in exhibitions limitations of some kind. K.T. seems to want to explore the new possibilities of exhibitions while taking into account these limitations” (Ibid, p. 9.). There is also the following passage:

Notwithstanding this, perhaps the motivation for feeling compelled to ask questions around the nature of exhibitions comes from the experience of holding exhibitions only to be robbed of the chance of them being viewed for reasons to do with history (for example, the precedence of the economy under capitalism) or the coronavirus pandemic.

Perhaps this is because, if one thinks that art should retain a kind of purity unaffected by any social circumstances whatsoever, then the state of the exhibition itself will seem to be estranged from this ideal.

(Ibid., p. 8.)

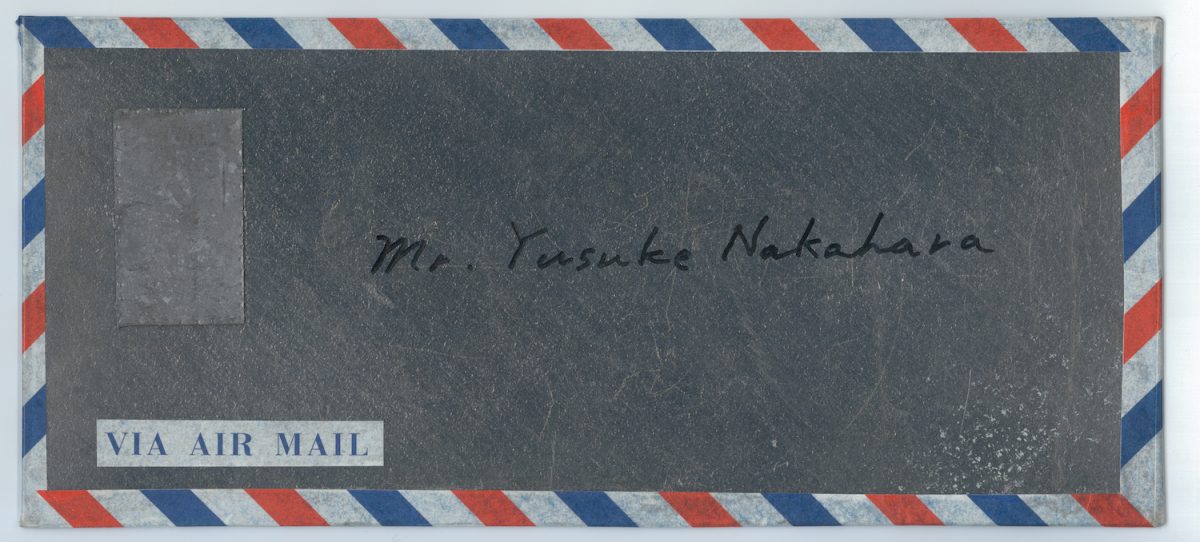

Separate to the questions Yokota posed, the context for Kawaguchi writing in this way included the existence of a certain critic as a dead person. It stemmed from the news of the death of Yusuke Nakahara, which reached Kawaguchi on the day of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. And by context, I mean that the above-quoted text begins with the following statement concerning Nakahara:

The Works of Tatsuo Kawaguchi includes an essay by Yusuke Nakahara entitled “On Tatsuo Kawaguchi – Concerning Material Imagination.” As it was a short essay, I almost certainly expected he would later write something more substantial. Unfortunately, he died before he was able to do so.

Focusing on this expression “short essay” and applying it to exhibitions, I am aware that there are such expressions as “small exhibition.”

As for the show at Y.S.G., I want to make it not a small exhibition, but a large exhibition. But is it really possible to stage a solo show worthy of the title “large exhibition” in a limited exhibition space?

It is possible.

(Ibid.)

Relation – Lead mail / Airmail to the dead: Yusuke Nakahara (2022). ©︎Tatsuo Kawaguchi, courtesy Shigeru Yokota Gallery.

Relation – Lead mail / Airmail to the dead: Yusuke Nakahara (2022). ©︎Tatsuo Kawaguchi, courtesy Shigeru Yokota Gallery.

Leaving aside for the moment the form of “It is possible,” I would like to focus here on how, via the form of the “short essay” Nakahara left behind, Kawaguchi discovered the crossing-thinking that led him to believe a “large exhibition” was possible. I use the term “cross-thinking” because a large exhibition usually means a show at a large facility such as an art museum, and even in spatial terms a normal comparison for a show at a small gallery would be a small exhibition. However, due to the pandemic, such a simple sense of scale has been lost. Regardless of how large the art museum might be, if one held a retrospective exhibition and it was unable to actually open, it would be neither large nor small. In that case, if one still wanted to stage a large exhibition anyway, the only option would be to reconsider from the ground up one’s thinking around exhibitions as events. In a society that prioritizes economic principles, large exhibitions naturally require large spaces in the sense of large vessels. However, if one bases oneself on the “relations” that Kawaguchi has continued to study for a long time, size does not necessarily have to be a physical thing. Between the two kinds of time mentioned above, which is to say time that can be measured with a clock and time recalled in our memory, there are no elements that can be compared based on size. Or rather, because it is not constrained by space, the latter can contain a much larger amount of time. This is because there is condensation. As mentioned in the example of a dream, it is also not unusual for time of between several years to several decades to be contained within a dream that in clock terms lasts just a single night. And was this not another kind of time that characterizes art?

Considered on this basis, one could also say that the long essay Nakahara never got around to writing is in a sense condensed within the short essay he left behind. In other words, this is precisely why so much thinking and so many exhibits have derived from that short essay, and why it led to this “Relation” exhibition as a “large exhibition” that was also a “small exhibition.” As well, in the same way that Kawaguchi himself was inspired by Nakahara’s short essay, this latest show has come to fruition by means of a method whereby a short essay expands in terms of its relations into a long essay while remaining physically small. In this sense, whereas a so-called long essay represents time that can be measured physically and spatially in terms of the number of pages, the time represented by a short essay in one’s memory does not come down to a simple comparison of size. A short essay exceeds physical and spatial restraints to become a long essay while remaining a short essay. Perhaps this is what is meant by a method that makes it “possible to stage a solo show worthy of the title ‘large exhibition’ in a limited exhibition space.”

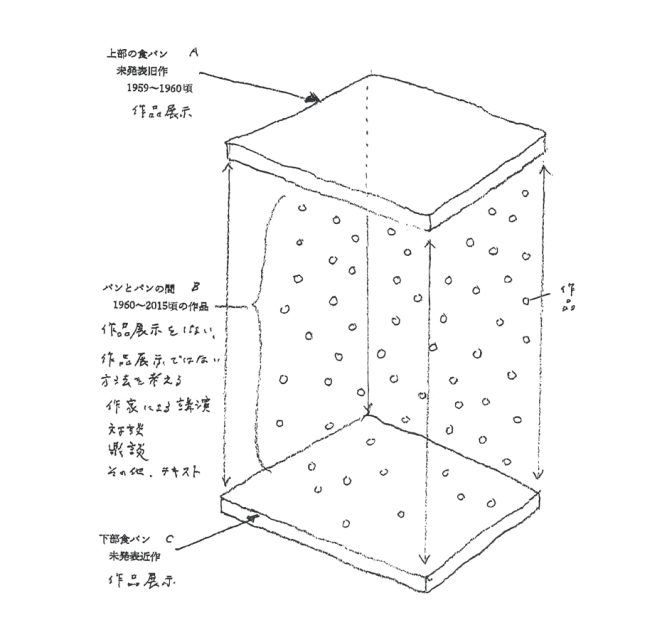

Earlier, the metaphor of a sandwich was brought up, but this sandwich structure itself is none other than a form as a metaphor whereby Kawaguchi maintained that a small exhibition could effectively become a large exhibition while remaining physically small. “In other words, a construction in which various fillings are inserted between two pieces of bread,” (Ibid, p9) Kawaguchi wrote, with the piece of bread on top of the sandwich corresponding to displays of previously unshown older works from around 1959-60 (A), and the piece of bread on the bottom also corresponding to displays of previously unshown works, but from recent years (C). And what about the crucial filling inserted between the two pieces of bread? This corresponded to works from around 1960-2015, but they were never displayed (absent), dealt with by “considering methods other than displaying them as artworks,” or to be more precise, through “lectures by the artist,” “dialogues,” “trialogues” and “texts, etc.” (B). With this method, by including “content that isn’t displayed,” the exhibition would not be restricted to a spatial vessel. Or rather, theoretically this content could be increased by any amount as it would not be affected by physical quantity or space. Accordingly, it could essentially become a large exhibition. Perhaps this “short essay” I am currently writing is also becoming part of the filling. But more importantly, part of this filling corresponds to a kind of memory, and to the extent that if we take a broader view they are “displayed,” the pieces of bread on the top and bottom – in and of themselves, the top belonging to the category of memory and the bottom to the category of space – belong to the category of actual space, while in the sense that they are “not displayed,” the part corresponding to the filling is summoned from memory time, so that these two different kinds of space and time themselves give rise to a new “relation.”

Illustration of Kawaguchi’s sandwich-form exhibition concept in Tatsuo Kawaguchi: Relation, p. 10. Courtesy Shigeru Yokota Gallery / Tokyo Publishing House.

Illustration of Kawaguchi’s sandwich-form exhibition concept in Tatsuo Kawaguchi: Relation, p. 10. Courtesy Shigeru Yokota Gallery / Tokyo Publishing House.

As can also be gathered from the fact that the first thing that jumps out at one after opening the cover of the catalog that is the source of these quotes is Relation – University Notebooks, this work itself is put together using a kind of sandwich form. However, while the form may be similar, the parts that correspond to the bread and the filling are quite different. In Relation – University Notebooks, there is no temporal difference between the parts that correspond to the pieces of bread on the top and bottom, both of which consist of newly made material. At the same time, whereas in the above-mentioned form the part corresponding to the filling was deemed to be “not displayed,” in this work it is actually “displayed” in the form of university notes from the past. In other words, in Relation – University Notebooks, Kawaguchi as someone formerly on the receiving end of teaching and now lost to eternity is sandwiched not from above and below but from the left and the right by Kawaguchi as someone who is still now able to teach. The fact that it is not from above and below but from the left and the right is also understandable on the basis that there is no longer any difference between being on the top or on the bottom, so whereas in the image of a sandwich things are stacked from bottom to top, in Relation – University Notebooks the notebooks are arranged upright from left to right, resulting in a form that is shifted 90 degrees to begin with. That said, perhaps with this work, as Kawaguchi suggests in the quote below, he had already made the transformation from a sandwich to a hot dog as part of a move to slightly different form.

Having thought all this, there is something I became aware of. I was able to confirm that A, B and C are consistent, and that the works are all related to each other. Based on this, I also think it is possible to think of them in terms not of a sandwich form, but of a hot dog form. Because in a sandwich, the pieces of bread on the top and bottom are separate, but in a hot dog, while there is a slit to insert things, the bread is not separated and remains connected. Though if the top is thin and there is a lot of filling, the bun might separate.

(Ibid., p. 17.)

But the reason I equated Relation – University Notebooks with a hot dog as opposed to a sandwich is not because “the top is thin and there is a lot of filling.” It is because Kawaguchi is in the time of a living person who can return to teaching at any time, and in this sense A and C are bread that is both joined and of the same quality. And even if it were a sandwich, because A and C would be completely different in terms of the time they belong to and the spatial and memorial qualities of those times, the mouth feel of each would be completely different, making for a rather unusual sandwich. But whether it is a sandwich or a hot dog, both are fast food and not grand French or Chinese meals that require time and effort to make, and in terms of the earlier comparison they can literally be called a “small dish.” While Kawaguchi emphasizes that “it is not the ability to eat them in breaks during work that is a characteristic of sandwiches, or the convenience of not requiring a table” (Ibid, p. 9), just as for Kawaguchi another foodstuff that has been emphasized in recent years is chocolate, perhaps there are sneaking similarities as with short essays and long essays, small exhibitions and large exhibitions, surrounding comparisons of “relations” between large and small that cannot be discussed solely in terms of a mere spatial comparison or a comparison of convenience, and surrounding the state of large and small “exhibitions” arising from this.

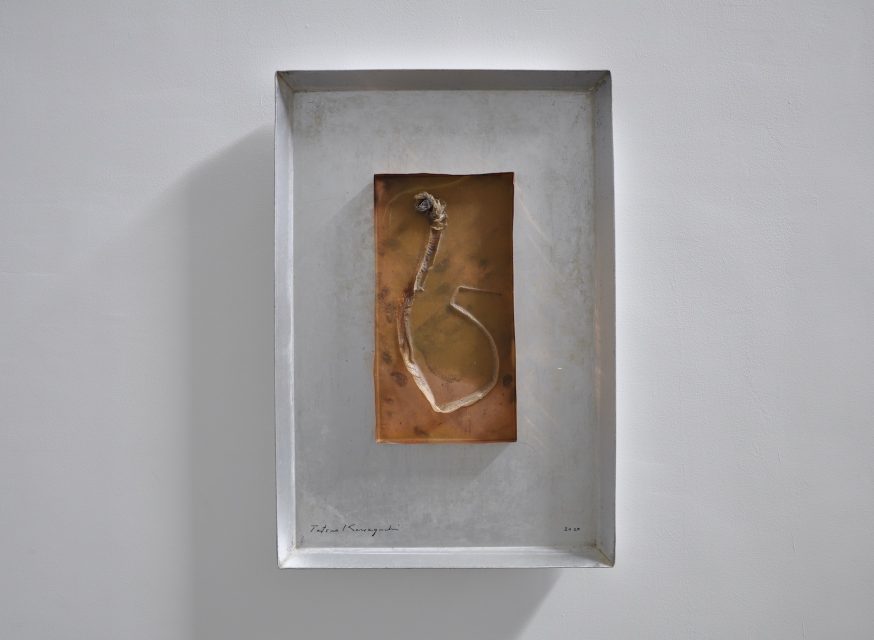

Relation – Life: Snake Time (2020). ©︎Tatsuo Kawaguchi, courtesy Shigeru Yokota Gallery.

Relation – Life: Snake Time (2020). ©︎Tatsuo Kawaguchi, courtesy Shigeru Yokota Gallery.

I have gone on at great length, but in the “exhibitions” arising from Kawaguchi’s “relations” by way of the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami and the coronavirus pandemic, the dead have clearly begun to be summoned. I say “the dead,” but a distinction can be made between the channels by which we can learn about them depending on whether the time is long (large) or short (small). The total number of victims that is reported almost daily via news coverage and similar channels is the former (large death), and is nothing more than a real number measured according to space, so to speak. As for the latter, due to its “smallness,” it is impossible to measure in the same way as the former. Because it is the death of each person (small death). And if it is individual, it is impossible to convert to something to begin with. In the same way that in wars the total number of deaths is referred to as a “cost,” “large death” – like large exhibitions – always leaves room to be connected somehow to economic principles. However, there is no such room in “small death.” Because such deaths are in a state of “heat death” that prevents economic metaphors and belong to the category “unrelated” in the sense that entropy is maximized. How can we, the living, form “relations” with these “unrelated”? What emerges by way of these latest displays by Kawaguchi is thinking and art that explores such impossibilities (as opposed to the possibilities that are so often discussed). Finally, by way of a conclusion, if possibility and impossibility are able to form an impossible relation through Kawaguchi’s works, then the very “patina” that arises from this, unconcerned even about Kawaguchi’s own life or death, is none other than the slightest room for what could be called possibility spanning the gap between humans and physical matter.

Postscript: I would not have been able to write this column had I not had the opportunity to meet and talk to Tatsuo Kawaguchi face to face at his studio. I would like to express my deep gratitude to Kawaguchi, who warmly welcomed this critic despite us never having met before, as well as to Kenji Kubota and Mifuyu Ishimizu at SNOW Contemporary. I would like to thank Satoshi Yokota and the staff at Shigeru Yokota Gallery / Tokyo Publishing House for their cooperation in reproducing so many images, including of past works.

“Tatsuo Kawaguchi: Relation” was held at Shigeru Yokota Gallery from April 25 through May 27 and “Relation – Seed / Copper” at SNOW Contemporary from April 22 through June 11. Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale 2022 opened on April 29 and continues through November 13 in the Echigo-Tsumari region of Niigata.

Noi Sawaragi’s other current activities

- Sato Kei: A Wonder (May 28–September 11, 2022, Kuma Museum of Art, Ehime), exhibition supervisor and main text for the exhibition catalogue.

- “Kazuo Umezz: The Great Art Exhibition” (September 17–November 20, 2022, Abeno Harukas Art Museum, Osaka (following its staging at Tokyo City View), exhibition concept advisor, and main text for and supervision of the exhibition catalogue.