Back to ‘The Art of Ground Zero’ – War, Plague, Nuclear Energy

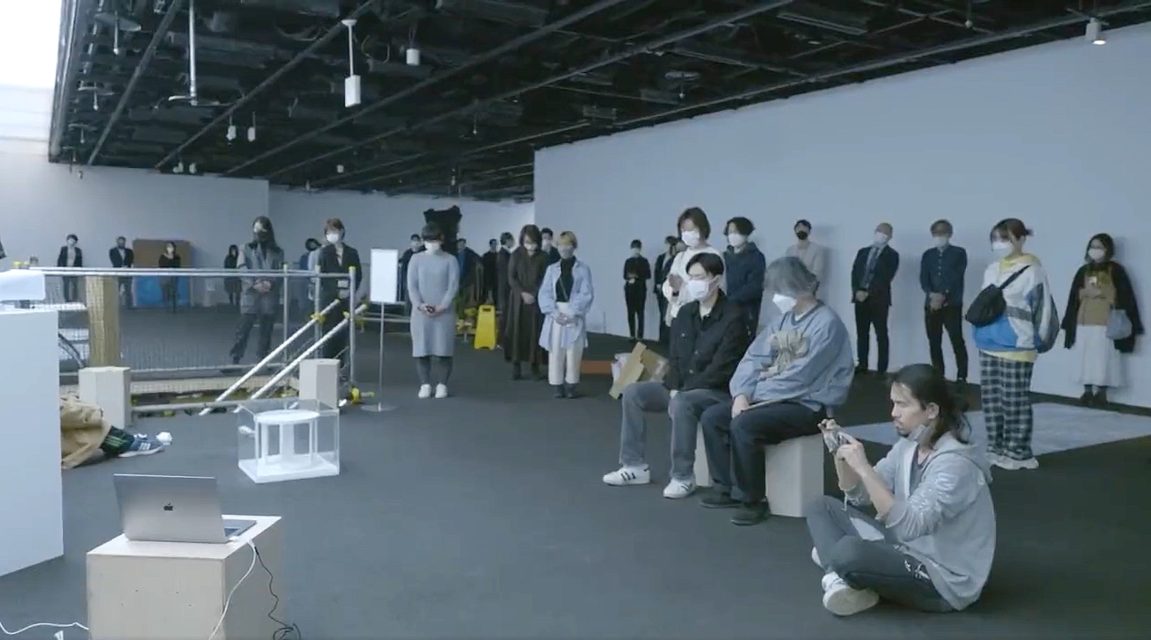

MOCAF (Museum of Contemporary Art Fukushima), March 11, 2022, Tomioka, Futaba, Fukushima. Photo courtesy: MOCAF.

MOCAF (Museum of Contemporary Art Fukushima), March 11, 2022, Tomioka, Futaba, Fukushima. Photo courtesy: MOCAF.

On March 11 this year, eleven years after the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, I was standing on a piece of vacant land in Tomioka, Fukushima. However, it was not the first time I had visited this site. Back when a house stood on it, I went inside briefly at the invitation of the owner. I wore a protective suit to reduce as much as possible the effects of radiation. This was some time after the inside of the building had been damaged by the violent shaking of the quake and then abandoned due to the nuclear accident, yet despite this it seemed as if time had stood still, with the owner unable to retrieve the items he wanted to remove. After my visit the house was demolished leaving the above-mentioned piece of vacant land.

Though the land is still vacant, it is the site of an art museum. It sounds odd to describe it this way, but I have written about this unique art museum, MOCAF (Museum of Contemporary Art Fukushima) in previous instalments of this column. As readers may recall, it opened exactly a year prior to March 11 this year. But it can only be visited once a year, for a few hours after 2:46 pm on March 11, which is the time the earthquake struck. On this day last year, apart from a sign indicating that an art museum was there, the only thing erected was a single white revolving door serving as the museum entrance.

MOCAF as it appeared on March 11, 2021. Photo courtesy: MOCAF.

MOCAF as it appeared on March 11, 2021. Photo courtesy: MOCAF.

Despite this, cars belonging to people who had heard about the museum arrived one after another at the parking lot across the road from the piece of vacant land. After the siren sounded at 2:46 pm and people finished their silent tributes to the disaster victims, visitors passed through the revolving door and entered the museum. I say “entered,” but the land on the other side was the same empty plot. There were no exhibition rooms and no exhibits. But something seemed to have changed as a result of passing through the door. Though one was on the same piece of vacant land, it appeared different before and after experiencing MOCAF. Later, the revolving door was dismantled by the visitors and turned into firewood, with everyone warming themselves by the resultant fire as the sun went down and darkness descended over the site. Afterwards, all that remained was a circular concrete slab embedded in the ground to serve as the foundation of the revolving door. As I have already described these events (see “Notes on Art and Current Events 95”), I will not do so again here. And so I visited the site again on March 11 this year, the museum opening for just a few hours just as it did the year before.

It was as if, after entering through that revolving door last year, we had never actually left the museum. This year a museum shop had been set up on the site, selling books related to the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami and serving coffee. In other words, it may be that MOCAF had actually been open all this time as if straddling the time gap of one year. As evidence of this, the concrete foundation on which the revolving door rested was still in place. Last year we entered through the revolving door that had been erected on this foundation, and this year moved on to the museum shop that had only just been built. And perhaps the exhibition rooms and exhibitions that are to come will continue across space-time for a few hours each March 11 from next year on. As to when we will be able to see the museum in its entirety, and what form these fragments will take overall among the memories in the back of our mind and our experiences, these things are still unclear. I can only park this body of mine – that (in spirit) has yet to leave the museum – in Tokyo, and look forward to the arrival of that day.

MOCAF on March 11, 2022. Photo courtesy: MOCAF.

MOCAF on March 11, 2022. Photo courtesy: MOCAF.

The museum, proposed and implemented by art director Yutaro Midorikawa (who is also director of MOCAF), resumed operations on March 11 this year just as it did last year after the siren at 2:46 pm and the silent tribute that followed. But some things were different from last year. Events from the silent tribute that began with visitors gathering around the circular foundation that remained from the previous year to the reopening of the museum were broadcast live via a monitor set up in a corner of Chim↑Pom’s “Happy Spring” exhibition at the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo. This meant that visitors to MOCAF in Tomioka and visitors to the Mori Art Museum could share the same moment of 2:46 pm on March 11 and pay their silent tribute together while remaining far apart in Fukushima and Tokyo respectively. Of course, this was more than just a case of simply sharing a location using the remote technology that has come to be taken completely for granted since the Covid-19 pandemic.

View of the silent tribute held at MOCAF at 2:46 pm on March 11 this year (2022). Photo courtesy MOCAF.

View of the silent tribute held at MOCAF at 2:46 pm on March 11 this year (2022). Photo courtesy MOCAF.

The same moment at the venue of “Chim↑Pom: Happy Spring” (Mori Art Museum, Tokyo).Video: Takehiro Ishitani.

The same moment at the venue of “Chim↑Pom: Happy Spring” (Mori Art Museum, Tokyo).Video: Takehiro Ishitani.

The nuclear accident at Fukushima was both an accident at Fukushima and something that occurred at a Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) facility. At the same time, it was premised on the asymmetrical power relationship of electricity being supplied from Fukushima to Tokyo. The nuclear accident occurred as a result of this. Consequently, those in Tokyo received the benefits of electricity from Fukushima, meaning they exacted this sacrifice, whereas those in Fukushima supplied electricity to Tokyo, as a result of which they were forced to make this sacrifice, making them the victims. The relationship between the two is not symmetrical. To combine the silent tribute held at an art museum on the upper floor of a skyscraper in the heart of Tokyo, that is like a symbol of development of the city that would not have occurred without electric power, and the silent tribute held in an unfinished art museum erected on a piece of vacant land in Fukushima, where everything has disappeared leaving just the wind to blow, is also to multiply the differences between the two and to reconstruct them in one’s imagination.

This year, however, brought an added new tension concerning nuclear power. The war that began with Russia’s sudden invasion of Ukraine was entering an unexpected phase. Russian forces had taken control of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, where in 1986, due to what it would be no exaggeration to say was the worst accident involving explosions and fires at a nuclear power plant in the history of civilization, radioactive material was released into the atmosphere. As a result, the supply of the electricity used to cool the radioactive material stored at the plant was stopped, and there were major concerns that 48 hours later, all power, including the backup supply, would be lost. (1) Because it was within this 48 hour period that I was standing on the piece of vacant land hosting MOCAF, the fact that I was in a place where a house had been demolished after its owner was unable to return due to a meltdown (an accident involving the release of radioactive material) at the Fukushima Daichi Nuclear Power Plant had a significance different from previous years.

Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, Pripyat, Ukraine (June 2013). Photo: Ingmar Runge

Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, Pripyat, Ukraine (June 2013). Photo: Ingmar Runge

“Chernobyl” was by no means something in the past. And even decades after the 1986 accident, the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant is far from being decommissioned. It was only a short while ago that the New Shelter was completed. This encloses the so-called sarcophagus that had been built around reactor No. 4 to prevent the spread of radioactive material, after strong radiation generated from inside made it impossible to maintain the sarcophagus’s long-term durability. In other words, Chernobyl is still ongoing, and this ongoing state has taken on a new vividness. One could even say that due to the war, the Chernobyl crisis has come back to life. In the unlikely event that one of the reactors was attacked and destroyed, it would be no surprise if radiation damage in excess of that caused by the earlier disaster occurred. No doubt the countries in the “west” that had become all too aware of the threat of radiation carried by the wind from Chernobyl in 1986 shuddered.

Until recently, no one really imagined the risk of terrorists occupying or attacking a nuclear power plant. Accidents were due to problems with managing reactors, and attacks from outside were complete blind spots. But following the advent of the “war on terror,” which differs from previous wars in that it is marked by the international spread of asymmetrical, local conflicts with invisible enemies, such attacks have suddenly begun to smack of reality. Nuclear power plants everywhere have had to reconfigure their safety standards on the supposition of a surprise attack from terrorists. When one thinks about it, this stands to reason. As long the nuclear power at these facilities can be controlled, they make a positive contribution to our lives, but if they explode, in principle they cause the same damage as a nuclear bomb. But even taking all this into account, who would have imagined that after the end of the Cold War a superpower like Russia would occupy by force a nuclear power plant in a neighboring country, plunging the world into a crisis?

I do not know the precise reasons why Russia did such a thing. But given that Moscow (the Kremlin) quickly gauged the severity of the Chernobyl disaster, which occurred during the Soviet era and is said to have been a factor in the collapse of the Soviet Union itself, it is only to be expected that in an extreme situation like a war they would use it to maximum effect militarily. And by military use, I mean simply occupying a site like Chernobyl without actually doing something like attacking a nuclear reactor would place an almost unimaginable amount of psychological pressure on western countries downwind from the site, so that even without actually introducing nuclear weapons, a nuclear power plant could become a potential nuclear weapon simply on account of its location.

In this sense, the wars of the 21st century that began with Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine are going to be completely different in nature from the wars of the past. In the 20th century, our image of World War III was of superpowers with nuclear weapons firing missiles at each other, with neither side winning and humankind facing the risk of extinction. But it may be that this first war actually waged by a major power in the 21st century has become a “nuclear war” without going as far as engaging the enemy with nuclear weapons, through the use of a nuclear power plant instead. In this sense, it is perhaps best to think of ourselves as already having entered an age of nuclear wars without having to wait for the old image of World War III to become a reality.

It was reported that immediately after electric power was supplied from Belarus, which is acting in support of Russia militarily, power at Chernobyl was restored. However, by no means have concerns disappeared. It was also reported that most of the Russian military forces had withdrawn from the area around Chernobyl, but a crisis that may potentially occur at any time remains etched deeply in the earth. Perhaps this is a scene from a world I previously thought unimaginable that appeared after I set foot inside MOCAF. That night following our silent tribute accompanied by a sense of impending crisis different from last year, as I stood in my room at a brand-new hotel in Tomioka and looked out the window at the soil remediation work, these were the things that occupied my mind.

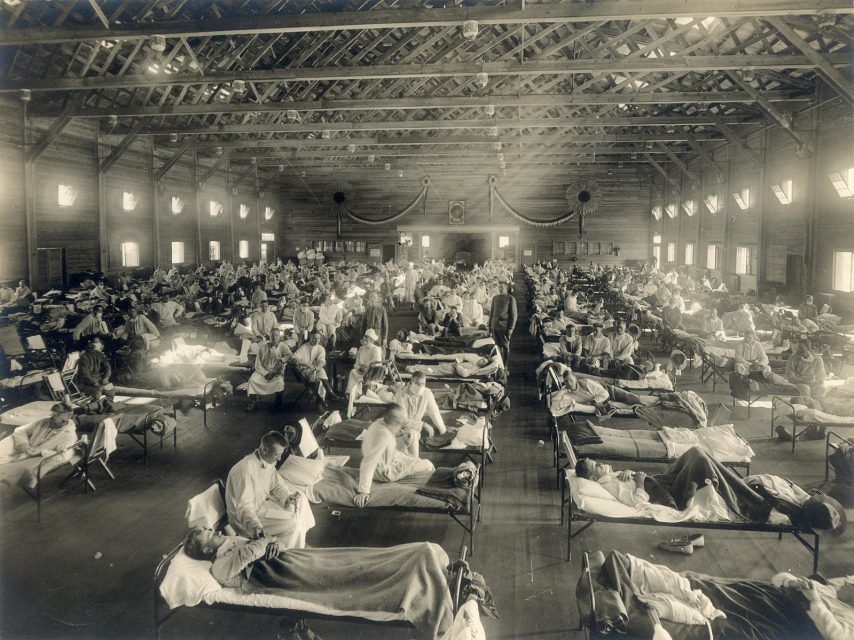

At the same time, I also experienced a sense of déjà vu, the kind that accompanies the confusion one experiences, for example, when one wonders whether it really is the 21st century; a feeling different from nostalgia, closer to the kind of agitated feeling one experiences when time seems to be going round and round in circles. I do not share the view of history as chronological progress, but even so this strange sense of déjà vu has brought to space-time a congested distortion in which multiple layers are intertwined. Take, for example, World War I at the beginning of the 20th century. Since the World Health Organization declared the spread of Covid-19 a pandemic on March 11 (!), 2020, the world has at last come to understand again the past as it concerns epidemics and human history almost as if it had been completely forgotten. What may have been pushed to the darkest corner of oblivion was the influenza pandemic caused by the so-called Spanish flu that spread around the world as if hot on the heels of World War I.

Soldiers from Fort Riley, Kansas, ill with Spanish flu at an emergency hospital ward at Camp Funston, Kansas, c. 1918. Photo: National Museum of Health and Medicine.

Soldiers from Fort Riley, Kansas, ill with Spanish flu at an emergency hospital ward at Camp Funston, Kansas, c. 1918. Photo: National Museum of Health and Medicine.

As the name suggests, a world war is accompanied by favorable conditions on a grand scale for the spread of a virus, whether it be as a result of military strategy or the vast number of refugees that are produced. Thus, combating communicable diseases is extremely important in terms of fighting the enemy and requires large amounts of time, manpower and money. This is even more the case during a pandemic, as demonstrated by the commonly accepted theory that during World War I, the spread of infection and the vast number of victims that resulted from it far surpassed the number of people who died in the fighting, and even hindered the ability of countries to continue to wage war, perhaps even hastening the end of the conflict. That the impact of this had a considerable lasting effect in the worlds of art and photography is something I discussed.

in the previous instalment of this column.

Despite everything, we had completely forgotten this. I wonder why this was so. I can only imagine that the erosion of life caused by a virus, which unlike a war is invisible, not the work of humans and not accompanied by the destruction of physical objects, is not congruous with the grammar around civilization, which is usually discussed using the language of “history” (the argument that war contributes to civilization, or rather that war itself is the essence of civilization, may also be made). There is no symmetrical relationship like that between friend and foe, and unlike war, an epidemic is a natural phenomenon. It is unclear who should be blamed, or who should be held responsible. Which is perhaps why we try with difficulty to prevent a catastrophe by emphasizing “friend/foe” metaphors such as “the war on the virus” and the importance of “winning.” In any event, it is clear that pandemics and wars are incompatible. One could even say that a pandemic has a “war-quenching” effect (in an unintentional sense, which distinguishes it from war-weariness or being anti-war).

Also despite everything, Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine occurred in the very midst of the global fight against the novel coronavirus in which it seemed humankind had become “one.” It was the opposite of World War I. Certainly, a military campaign during a pandemic brings with it the risk of a large-scale spread of infection. But might this be the very reason that Russia embarked on this war? At a time (which no one associates with war) when the leader of a country can openly state that staying at home is the greatest contribution people can make for the sake of humankind, that one of the world’s military superpowers launched a large-scale offensive against a neighboring country, resulting in the peoples of both countries taking up arms and fighting each other, can only be called completely “unexpected.”

Naturally, while vast numbers of refugees are crossing international borders to escape the fighting, we do not see those accepting them checking the temperature of every single one or ensuring they disinfect their hands. There are more important things to worry about. In light of this, I would like to retract a part of the above hypothesis concerning the “war-quenching” effect of the pandemic. Contrary to what occurred during World War I, there are wars that can break out precisely because there is a pandemic. This is also an instance of déjà vu distorting space-time in a congested fashion. Even when very similar events occur, the order is different or the causal links go haywire. Which is why it is different from nostalgia. If anything, it is on account of the similarities that the sense of being at cross-purposes is so scary.

On the subject of a strange sense of déjà vu, I get the same feeling when I hear the term “post-corona,” which has come to be used often since the pandemic struck. Since I have remarked elsewhere on the complex meaning of this term, I will refrain from commenting further on that subject.(2) What I would like to discuss here, however, is a question one no longer hears these days, and that is what exactly did “post-modern,” a term that was debated here and there for a time, mean? Even if it a question no longer asked, it not, needless to say, because the issue has been resolved. Perhaps the very premise behind such a question was mistaken to begin with. If so, then surely in the questioning of “post-corona,” too, there is a chance that there may be no answer to begin with, or that the premise itself may be unreasonable. The reason I feel this way is because I sense that the period when people began to discuss this “post-modern” issue and the present age, when a major accident and a war have occurred one after another on either side of a pandemic, were repeated in a past more recent than the period around World War I.

To begin with, among epidemics and nuclear accidents and wars there is a strange cyclicity, or to reuse a term from above, a sense of déjà vu. Even looking back over the past few decades, it was in 1983 that the HIV virus that causes AIDS was isolated (meaning that the virus was captured in a specimen enabling it to be analyzed), and in the late 1980s and early 1990s that numerous celebrities, intellectuals and artists lost their lives as this “incurable illness” triggered premonitions of death around the world. Even today, while effective medications have been found and it can no longer be called incurable, an effective vaccine has yet to be developed and the number of people who are infected or have symptoms continues to rise. As well, as mentioned above, in was in 1986 that at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, which has come back to life like the scene of an accident that is still in progress, an unprecedented accident involving explosions and fires inside a nuclear reactor occurred, as a result of which the fear of invisible radiation spread around the world. The democracy movement that suddenly became active in Eastern Europe at around that time grew to the point where in 1989 it tore down the wall separating East and West Berlin, and two years later, in 1991, the Soviet Union, which had been the control tower of the east during the Cold War, disappeared as if it had never actually existed. After the now-forgotten stage in which they were known as the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the various countries left this grouping to become republics, and so it was that the damaged Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant passed into the hands of Ukraine.

Then the Cold War ended (though as seen on the Korean peninsula, in the Far East it has actually not ended at all), and freedom and democracy as represented by the US and in economic terms capitalism became the principles at the global level. But just as it appeared as if globalism would completely cover the world, the Iraqi army led by Saddam Hussein launched an invasion of neighboring Kuwait. In response, coalition forces attacked Iraq and Bagdad was bombed in what became known as the Gulf War. It is said that this war was one of the factors behind the coordinated terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and the aerial bombing of Afghanistan conducted by the US in retaliation for these attacks ultimately led to the Iraq War in which the US along with the UK invaded Iraq on the pretext that the country secretly possessed weapons of mass destruction. Though no evidence was found that Iraq did have WMDs, repeated attacks were conducted throughout the country using depleted-uranium shells and other inhumane weapons resulting in many casualties. It goes without saying that this created a breeding ground for groups such as the Islamic State that later became targets of the War on Terror. And throughout this period the term “post-modern” continued to be discussed.

And so since 1983 when the HIV virus that generated the AIDS epidemic was identified, we have been continually tossed about by nuclear accidents and wars. This cycle has by no means been resolved, and almost as if it has a kind of distorted cyclicity, like a virus that returns again and again and spreads by transforming into new strains that produce different symptoms, after the Fukushima nuclear accident triggered by the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, in 2020 a pandemic was declared due to Covid-19 and two years later, in 2022, a “war” broke out in the form of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

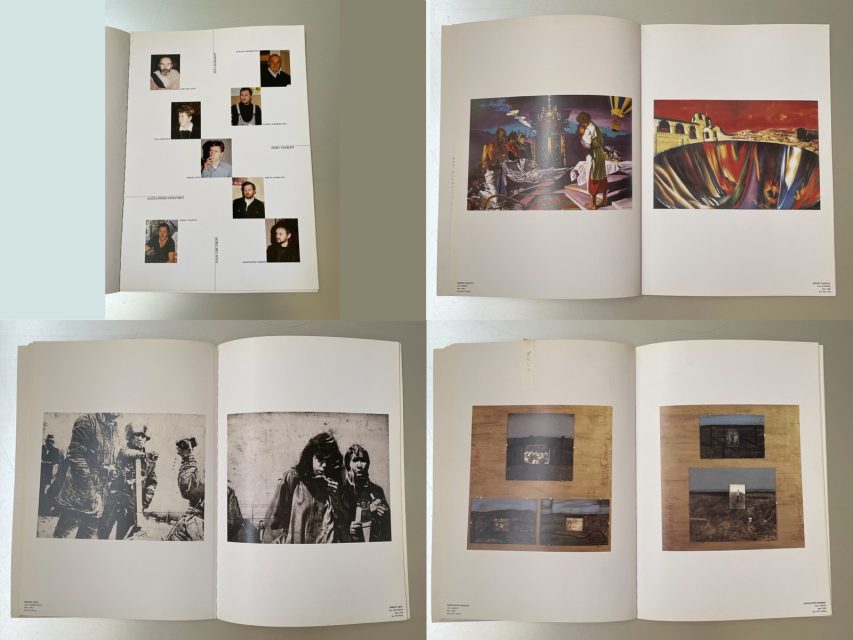

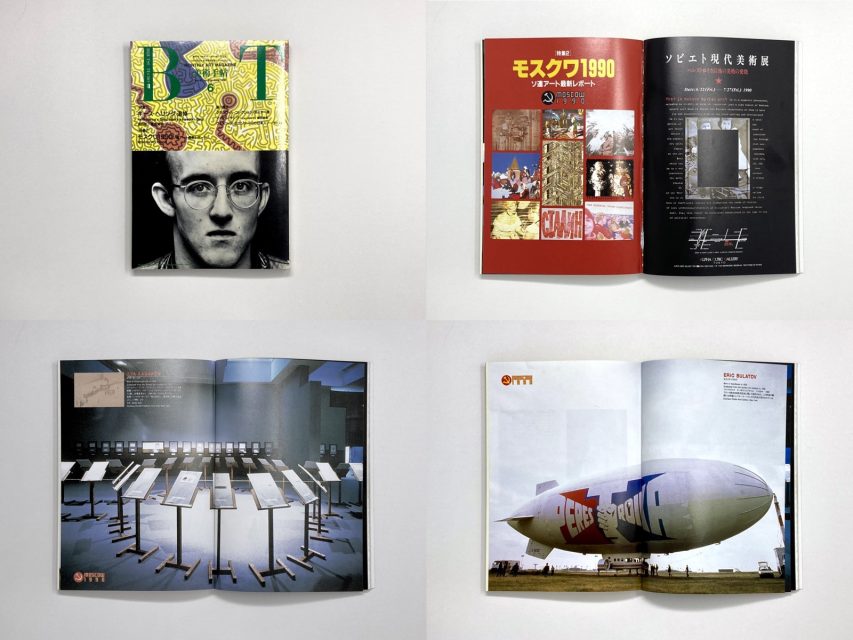

Looking back, the first time I got on a plane and went overseas and so had to get a passport was when I went to Moscow and Leningrad to research trends in contemporary art in the Soviet Union under perestroika. This was in 1990. The trip lasted just under a month and resulted in an exhibition, a record of which remains in the form of a catalogue.(3) The report I wrote was published as a feature in the June 1990 issue of Bijutsu techo, in which the top feature article was an obituary of Keith Haring, who died of AIDS. Some people may have already forgotten it, and the younger generation may not even know it, but at this time, too, an epidemic, a disintegrating Soviet Union and the fear of invisible radiation were spreading around the world, while the aerial bombardment of Bagdad (ie, war) of January the following year was fast approaching. And at around this same time in Leningrad (Saint Petersburg), a former KGB agent by the name of Vladimir Putin was launching his political career.

Pages from the catalogue to the exhibition “Soviet Contemporary Art 1990.” Clockwise from top right: Works by Sergey Bazilev (b. 1952, Kiev, Ukraine), Konstantin Pobedin (b. 1956, Kharkiv, Ukraine), Sergey Geta (b. 1951, Kiev, Ukraine), et al. Of the twelve exhibiting artists seven were from Ukraine. In addition to the above three, they are Alexander Gnilitsky, Ilya Kabakov, Ivan Chuĭkov, Erik Bulatov, Eduard Gorokhovsky, Evgeny Gorokhovsky, Olga Grechina, Oleg Vassiliev, and Gashunin Nikita.

Pages from the catalogue to the exhibition “Soviet Contemporary Art 1990.” Clockwise from top right: Works by Sergey Bazilev (b. 1952, Kiev, Ukraine), Konstantin Pobedin (b. 1956, Kharkiv, Ukraine), Sergey Geta (b. 1951, Kiev, Ukraine), et al. Of the twelve exhibiting artists seven were from Ukraine. In addition to the above three, they are Alexander Gnilitsky, Ilya Kabakov, Ivan Chuĭkov, Erik Bulatov, Eduard Gorokhovsky, Evgeny Gorokhovsky, Olga Grechina, Oleg Vassiliev, and Gashunin Nikita.

Cover of the June 1990 edition Bijutsu techo and pages from the feature article “Tokushū 2: Mosukuwa 1990 – Soren āto saishin repōto” [Special feature 2: Moscow 1990 – The latest report on Soviet art], introducing works by Ilya Kabakov (bottom left) and Erik Bulatov (bottom right).

Cover of the June 1990 edition Bijutsu techo and pages from the feature article “Tokushū 2: Mosukuwa 1990 – Soren āto saishin repōto” [Special feature 2: Moscow 1990 – The latest report on Soviet art], introducing works by Ilya Kabakov (bottom left) and Erik Bulatov (bottom right).

The Cold War is said to have ended, but has it really? If it has, then surely NATO, which is regarded as one of the factors behind Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, should have been dissolved rather than strengthened. Could it be that globalism’s victory was in fact localism in disguise? Indeed, could it be that one of the conclusions arrived at by globalism was the advent of an age of pandemics in which it is right to confine people to their homes? It is precisely because of this that being “domestic” can be an act of opposition against both globalism and localism, as I have stated repeatedly in this column to date.

Perhaps we have slipped dimensions, from 1991 when the Soviet Union dissolved straight to 2022. Impossible, I know, but it feels as if we have. Does a country with as many control mechanisms and as much military power as the Soviet Union really dissolve as if it were a dream? Why did the situation not develop into a large-scale civil war to begin with? In the decades after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, is it not true that things resemble not the end of the Cold War (ie, the victory of globalism), but a “never-ending ending” arising from the end of the Cold War being so drawn out? Russia’s merciless invasion of Ukraine can only be called perverted in a world based on the principles of globalism, but what if the Soviet Union of the Cold War era was still in existence?

In 1989, when the Showa era ended and the Heisei era began, the Berlin Wall came down. When the curtain closed on the Heisei era and the Reiwa era began, the world was hit by a pandemic, in the midst of which Russia started a war as if the Soviet Union had been revived. The Heisei era was also a time that gave rise to a feeling of déjà vu with respect to the Showa era. War, the Olympics, a natural disaster and an epidemic, which is to say the unpleasant repetition of “Bubbles / Debris” – when one thinks about it, the problem of the post-modern is a questioning of déjà vu itself. If post-modernism was symbolically manipulating modernism itself (the pursuit of universality) as a past phenomenon, then perhaps the term “post-corona” that has returned after the pandemic is similarly not a questioning of the future as of old, but a problem of a distorted sense of déjà vu, or a kind of simulacrum in which the ghost that is post-modernism returns in a terrifying form, causing humankind to endlessly degenerate.

1. Later, on March 10, the Russian Ministry of Energy revealed that power to the nuclear power plant was restored with electricity supplied from neighboring Belarus. On March 15, the International Atomic Energy Association (IAEA) reported based on information from the Ukrainians that the plant had been reconnected to Ukraine’s own power grid. And on March 31, the national nuclear energy generating company of Ukraine, Energoatom, announced that Russian military forces had withdrawn from the plant.

2. A publication associated with the Post Covid-19 Arts Fund, on whose selection committee I served, is due to come out in early summer.

3. “Soviet Contemporary Art 1990,” Alpha Cubic Gallery, Tokyo, June 22–July 27, 1990.

Other Noi Sawaragi current activities

- Sato Kei: A Wonder (May 28–September 11, 2022, Kuma Museum of Art, Ehime), exhibition supervisor and main text for the exhibition catalogue.

- “UNZEN – The Heisei Eruption: Through Sunamori Katsumi and Mitsuyuki Toyohito” (June 3–18, 2022,

Tama Art University Art-Theque, 2F Gallery, Hachioji, Tokyo), exhibition supervisor and main text for the exhibition catalogue. He will also participate in the related talk “Hyōgen to kiroku, kioku no keishō Unzen kara hajimeru” [Inheritance of Expression, Record, and Memory: Beginning with Unzen”] together with Yukinori Okamura (Maruki Gallery for the Hiroshima Panels), Keiko Sasaoka (photographer), and Kazura Sunamori (President, Sunamori Media Archives). - “Kazuo Umezz: The Great Art Exhibition” (September 17–November 20, 2022, Abeno Harukas Art Museum, Osaka (following its staging at Tokyo City View), exhibition concept advisor, and main text for and supervision of the exhibition catalogue.