Katsumi Sunamori – Implications of the Scenery (2)

From Katsumi Sunamori Kama Tida: Osaka Nishinari (1989). All images: © Katsumi Sunamori Photography Office

From Katsumi Sunamori Kama Tida: Osaka Nishinari (1989). All images: © Katsumi Sunamori Photography Office

In my last column, I delved into the question, Who is Katsumi Sunamori? and discovered the answer was so complex one could have written an entire book. Here, I would like to keep things to a minimum and expand towards a theory while providing a summary-like introduction.

Sunamori was born in 1951 to a Filipino father and a mother from Amami Oshima. His parents met after leaving their respective places of birth and traveling to the island of Okinawa to find work. The Philippines was ruled by Japan during World War II, although this came to an abrupt end after the war when it came under U.S. control. Meanwhile, Amami Oshima was also cut off from Japan and placed under U.S. control after the war, but because it did not become the site of military bases like Okinawa, it was unable to partake of the “special procurements” associated with the Korean War. This resulted in many residents being reduced to poverty and moving to the island of bases, Okinawa, to make a living. And so it was that Sunamori’s father, Saberon, and mother, Kazuko, met amid a tumultuous age in which subjects of domination and rule experienced reversals at a dizzying pace, and their own affiliation seesawed back and forth accordingly. Soon after their meeting, however, the Korean War changed completely the circumstances surrounding Okinawa. As a result of the military bases becoming permanent fixtures in Okinawa, the U.S. military looked to local Okinawans to meet their employment needs. Because of this, Saberon, who lived in Okinawa as a civilian employee of the military, lost his job, and together with Sunamori, who by this time had already been born, moved to Kazuko’s home island of Amami Oshima. However, there was no work for Saberon, and when Sunamori was eight years old, his father returned to the Philippines and before long all contact with him was lost. It would be no exaggeration to say that the yearning for his father that Sunamori experienced at this time determined the course of his life. At the same time, having lost Saberon, who had supported the family financially, Kazuko fell into extreme poverty, and when Sunamori was fifteen she suddenly died from ill health.

Through the introduction of a relative, Sunamori moved to Osaka to support himself, following which he grew increasingly passionate about meeting his father again. Using his father’s name in his ring name, Saberon Sunamori, he debuted as a professional boxer out of the Kanbayashi Boxing Association, a gym in Osaka. Sunamori thought that if he became a champion using this name, his father would hear about it somewhere and they might be able to see each other again. However, despite achieving favorable results and eventually gaining an opportunity to fight for the title of Western Japan Rookie of the Year, after agonizing over his future Sunamori decided to give up boxing that very day. This was a reflection of his complex emotional state in which antipathy about his victory being decided without having fought after his opponent withdrew from the contest, the emotional turmoil of achieving glory by punching and hurting people, and uncertainty over whether he could hold his own against a formidable rival who had advanced through the ranks in eastern Japan were all jumbled together.

In a complete change from boxing, drawn by memories of his camera-loving father, Sunamori began working at a film-processing lab in Osaka. Before long he was working at a camera repair plant during the day and a cabaret during the night in order to pay for his tuition at Osaka Photography College (present-day Visual Arts College Osaka), where he acquired the skills that would enable him to begin working as a freelance photographer after graduating. After finishing work at the advertising agency where he was employed for a year, Sunamori became interested in photographing the former squatter settlement known as Genbaku Slum in Hiroshima that he happened to visit. He also learned of the existence of Korean victims of the atomic bombing who, despite being exposed to radiation in Japan, were not given compensation for medical treatment and were living in temporary housing and enduring other hardships, and began to photograph them. In the course of photographing these subjects, Sunamori learned that not only Koreans, but many other victims of the atomic bombing who had lost their jobs due to poor health had left Hiroshima and ended up in Kamagasaki in Osaka, where they did manual labor as day laborers. But he did not photograph them right way. At the time, Kamagasaki was already attracting the attention of a large number of journalists and photographers as a place of social indictment. But Sunamori did not approve of either the intrusive candid photography or the shooting from a journalistically appropriate distance that these people practiced. Instead, he wanted to move to Kamagasaki and live, eat and drink alongside his subjects. Sunamori also learned that a large number of Okinawans had moved to Osaka’s Taisho Ward, the ward next to Nishinari Ward in which Kamagasaki was located. And so it was that in Kamagasaki by way of Hiroshima, Sunamori was reunited once again with his former drifting self from Okinawa. In the end, it was not until a long time later that he took photographs in Kamagasaki, which he did while commuting from outside the area, and showed them in public. But he lived there for fifteen months until leaving in 1979.

From Katsumi Sunamori Kama Tida: Osaka Nishinari (1989)

From Katsumi Sunamori Kama Tida: Osaka Nishinari (1989)

With the photos of Kamagasaki that were presented in this way, Sunamori first made his mark as a photographer. In 1984, he earned an honorable mention in the 4th Document File Awards in the magazine Monthly Playboy (Shueisha) for “Osaka Ruten 1978-1983,” a series he shot in Kamagasaki in color, which was still unusual at the time. And this series came to fruition as the photobook Kama Tida: Osaka Nishinari (IPC, 1989), which remains one of Sunamori’s greatest works. Apparently Sunamori was rather insistent about using the words “Kama Tida,” whose meaning would have been difficult to grasp for those hearing them for the first time. At this point, while referencing an essay by Sunamori’s eldest daughter, Kazura, who served as his assistant in his later years and since his death has independently put in order, maintained and studied the photos and other materials he left behind, I would like to consider this as well as offer my own criticism. What concerns me about Kama Tida above all is the title. According to an interview Kazura Sunamori conducted with the former chief editor at IPC, Yusuke Nakagawa, which is also mentioned in her essay, when Nakagawa “told Sunamori that if they used the title Kama Tida no one would understand what it meant, Sunamori refused to yield, saying that he would not accept another title.” So why was Sunamori so insistent about these words?

The first thing that comes to mind is that “Kama” denotes Kamagasaki. As for “Tida,” if I had not been told I would not know its meaning. This is an Okinawan word meaning “sun.” So it could be that “Kama Tida” means “the Kamagasaki sun.” Unfortunately we cannot verify that this is the actual meaning because the person concerned is dead, but for Sunamori, who from a young age lived alongside those at the bottom of the social scale and shared their suffering, it seems reasonable to conclude that the sun alone appeared to be a ray of hope that shone on everyone equally irrespective of their wealth or social status. For example, Kazura Sunamori’s essay includes the following memorable passage.

The first photo in Sunamori’s “Kamagasaki” shows two stray dogs mating on the street in the early morning. He regards those looking in from the outside, including himself, as “akin to stray dogs,” and uses this to symbolize the entrance to Kamagasaki. As the air that became numbingly cold overnight begins to warm slightly with the rising of the sun, the sun illuminates every nook and cranny and people’s lives begin again. (From Kazura Sunamori, “Shashinka Sunamori Katsumi ga mitsumeta Kamagasaki no taiyo” (The Kamagasaki sun that photographer Katsumi Sunamori gazed at), underling added, notes in parentheses omitted.)

From Katsumi Sunamori Kama Tida: Osaka Nishinari (1989)

From Katsumi Sunamori Kama Tida: Osaka Nishinari (1989)

Put simply, for Kamagasaki’s day laborers, many of who spend the night on the street, it is not artificial light but natural sunlight that signals the beginning of each day, which coincides with the beginning of the activity that sustains their lives. In other words, in our society, in which the virtue of civilization has become difficult to observe on a daily basis, Kamagasaki is one place where the fact that the sun is the source of life and the basis of living is utterly clear. In the example of the photo of the mating stray dogs mentioned above, both animals are bathed from behind in light from the rising sun, the breath they exhale into the still cold air is white and their silhouettes dark and the details unclear. It would seem that the hidden subject here is not so much the mating dogs but the sun behind them announcing the arrival of the new day. I say this because in an unpublished text, Sunamori wrote, “Kama is an abbreviation of Kamagasaki, and Tida a reference to the fact that a large number of people from Amami and Okinawa live in this part of Osaka. Through my lens, I wanted to at least provide them with some ‘sunlight.’ I wanted them to discover in some form or another a ray of hope.” (Quoted from “N-san e no tegami” (Letter to N-san) in the same essay by Kazura Sunamori referred to above, underlining added.)

We cannot know for sure whether in photographing Kamagasaki in color with the sun as the light source (as if photographing the southern islands flooded with color?), Sunamori had in mind the photobook Taiyo no enpitsu (The Pencil of the Sun) (Camera Mainichi, 1975), in which his predecessor the great photographer Shomei Tomatsu captured in bright light the southern islands from Okinawa to Southeast Asia. However, if he had seen Tomatsu’s Taiyo no enpitsu, which, based on a unitary continuity via the medium of the borderless ocean, captured the colorful world of the transterritorial region stretching from the islands of Okinawa to the islands of Southeast Asia, including the Philippines, a world that could not be fully grasped within the confines of the nation-state/territory of Japan, there is no doubt it would have had a strong impact on Sunamori. In fact, Sunamori had previously spoken of how the ocean that stretched out before him was a scene of hope, however faint, connecting his own place of residence and that of his lost father. Tomatsu captured this using the universal light of the “sun” as a “pencil” (the title derives from The Pencil of Nature by one of the inventors of photography, William Henry Fox Talbot) and extolled it loudly. Taiyo no enpitsu was also pioneering in that it depicted in the form of a series of color photographs the southern islands including Okinawa. Perhaps this was an important catalyst behind Sunamori’s decision to capture the life stirring in Kamagasaki with “the pencil of the sun” (Tomatsu), not as the kind of social indictment in which realism attained through the use of black and white photography prevailed, but using color photography to depict the streets on which lives with various histories intermingled and overflowed. Considering this, it is perhaps possible, albeit only slightly, to understand why Sunamori was so fixated on calling his own work “Kama Tida (The Kamagasaki Sun).”

There is another history that considerably expands the scope of our interpretation when discussing Sunamori as a photographer. From around the time that Sunamori first made a name for himself as a photographer with his Kamagasaki series, in quick succession major publishing companies launched weekly pictorial magazines that took the nation by storm with gossip and scandalous photos that made no distinction between public and private affairs. In fact, Sunamori himself produced “results” on numerous occasions as a photographer providing photos to the likes of Kodansha’s FRIDAY and Kobunsha’s FLASH. Even amid the increasingly scandalous nature of these weekly pictorial magazines, there was one series of photos taken as an incident unfolded that had an especially dramatic impact. Kazuo Nagano, chairman of Toyota Shoji, which had swindled tens of thousands of victims out of more than 200 billion yen, had shut himself in his apartment after being besieged by journalists and news photographers, when two men broke a window and entered from a passageway and proceeded to stab him to death in public. It was only recently that I learned that the mostly widely circulated photos of this incident were in fact taken by Sunamori. How on earth could the photographer who compared the Kamagasaki sun to the light that offered hope for living (ie, the pencil of the sun) and the photographer as intruder who unmercifully exposed the hidden aspects of society and pursued scandal and gossip coexist within Sunamori?

A photo taken by Sunamori of the scene of the stabbing to death of the chairman of Toyota Shoji (1985). In front of a group of reporters who had besieged the chairman’s home, two men broke a window and entered the apartment. Amid the turmoil, Sunamori climbed the stairs of a neighboring building and photographed the events that followed. His photo of the two men exciting the apartment through the window appeared in the July 5, 1985 edition of FRIDAY.

A photo taken by Sunamori of the scene of the stabbing to death of the chairman of Toyota Shoji (1985). In front of a group of reporters who had besieged the chairman’s home, two men broke a window and entered the apartment. Amid the turmoil, Sunamori climbed the stairs of a neighboring building and photographed the events that followed. His photo of the two men exciting the apartment through the window appeared in the July 5, 1985 edition of FRIDAY.

Sunamori then ran back to the apartment building where the incident took place and photographed through the window the room where the chairman died. This photo was published in the above-mentioned magazine, shocking the world at large. The film he used at the time included shots like the above, giving an indication of Sunamori’s movements as events unfolded quickly at the scene. “I didn’t use the finder. I just clicked the shutter again and again.” (Katsumi Sunamori, Sukyandaru wa osuki? (Do you like scandals?), Mainichi Newspapers, 1999)

Sunamori then ran back to the apartment building where the incident took place and photographed through the window the room where the chairman died. This photo was published in the above-mentioned magazine, shocking the world at large. The film he used at the time included shots like the above, giving an indication of Sunamori’s movements as events unfolded quickly at the scene. “I didn’t use the finder. I just clicked the shutter again and again.” (Katsumi Sunamori, Sukyandaru wa osuki? (Do you like scandals?), Mainichi Newspapers, 1999)

In thinking about this event, it would seem that the emotional turmoil Sunamori experienced around the time he gave up boxing foreshadowed it. It is probably certain that in order to accept as a boxer the harsh reality of achieving results by punching his opponents and damaging their bodies, Sunamori, who as a child hated arguing and was kind to everyone, needed to adopt both “another personality,” which he got by using his father’s name as his ring name, and a practical approach to “fighting” as a means of being reunited with his father. However, if this were the whole story, then boxing was a means of achieving a result, and could not possibly be a goal deeply rooted in his self.

What is interesting is that from a certain point Sunamori came to regard boxing as a kind of self-expression. According to Kazura Sunamori, one of the pieces of writing left behind by her father, “Gusobana” (Flowers for the afterlife) (unpublished, date of writing unknown), includes the following statement.

If all one does is watch it, boxing is a thrilling physical battle. However, inside the minds of boxers this is not the case. They confront each other using advanced techniques they have practiced. The key is the extent to which they can drive their own blows into their opponent, who attacks with fangs bared, while avoiding their opponent’s punches. This is a skill, which if refined becomes a form of “beauty” that flowers in the ring. It remains imprinted in the minds of fans as a beautiful form of “expression.” Perhaps the reason I, someone who had no experience at all of fighting, was able to enter the world of boxing without any reservations was because I was under the illusion that if I trained hard enough I could do so. “Beauty” was possible, “expression” was possible. (From the same essay by Kazura Sunamori referred to above, underlining added.)

If we take the terms “beauty” and “expression” that Sunamori uses in the context of boxing as a martial art and apply them to photography as the pursuit of scandals, we can easily see Sunamori as a photographer who, using the weekly pictorial magazines as his stage, did not seek the kind of “destruction of the privacy” of his subjects that was criticized by the public by chasing scoops, but tried to capture scenes that would long remain in viewers’ memories by using brilliant photographic techniques (in fact, I still retain a vivid impression of the scene of the stabbing to death of the Toyota Shoji chairman), a photographer who pursued not gossip but beauty and expression. In fact, Sunamori approached the scene in question with speed and precise judgment, and this along with his superior skills as an intruder call to mind the unique traits of a professional boxer. The following is another quote from a Kazura Sunamori essay that touches on Sunamori’s photographs of a different incident (the robbery and rape of a female university student by a serving teacher).

Sunamori entered the police station without permission and waited for the moment when his target returned to the Suma police station after being committed for trial and felt relaxed after escaping the press outside, photographing him as they encountered each other. Exposed to the camera flash from a short distance, the detective raises his right arm in an effort to shield the suspect. Exhausted after being questioned, the suspect’s hands, which are cuffed and tied to a cord around his waist, are frozen in a halfway position in a manner that appears almost casual. It is the kind of situation in which one would normally want to conceal one’s face, but unfortunately the cord is not long enough. His eyes are blank and cast downward. The photo appears to have been taken suddenly, the oblique angle and blurring of the background adding to the sense of speed and giving rise to an ambience suggestive of a photo taken on the spur of the moment. (Kazura Sunamori, “Unzen/Fugendake saigai shashin kara yomitoku Sunamori Katsumi no riarizumu” (Katsumi Sunamori’s realism as interpreted based on his photographs of the Mount Unzen/Mount Fugen disaster), paragraphing omitted, underlining added)

It would not be strange at all to interpret this as depicting a boxer in the ring judging the situation in an instant and repeatedly directing punches at an opponent’s vital parts in order to cause decisive damage, while being barely able to stand just before a knockdown. In fact, Sunamori’s physical training and honing of his skills as a boxer were probably useful in enabling him to demonstrate his abilities as a fighter (ie, photographer) able to rush to the scene, thread his way through the tangle of information and accurately arrive at the core of the matter and slip through the multiple layers of defenses in order to obtain the decisive image. And at the same time Sunamori likely saw in this his own kind of “beauty” and “expression” as a photographer. “‘Beauty’ was possible, ‘expression’ was possible,” even while pursuing gossip.

Ultimately, however, Sunamori rejected boxing, being unable to regard without question the mutual damaging of bodies as “beauty” or “expression,” but just as he indicated when he later concluded that he was “under the illusion that if I trained hard enough I could do so,” he instead devoted himself to becoming a scandalous gossip photographer, being similarly unable to abandon the idea “‘beauty’ was possible, ‘expression’ was possible” there. In other words, precisely because of this, it seems that after taking these shocking photos, Sunamori needed to present the Kamagasaki series once again, this time not as “Osaka Ruten” but as “Kama Tida,” which is to say not as aimless drifting but as a ray of hope. And so, from the time of the publication of Kama Tida, Sunamori began taking photographs as artworks purely for himself.

From Katsumi Sunamori Okinawa Amami Manila (1995) View of Naze Bay.

From Katsumi Sunamori Okinawa Amami Manila (1995) View of Naze Bay.

The crowning achievements of this endeavor later came to fruition as the photobook Okinawa Amami Manila (CREO, 1995). With this work, for which he won both the 15th Domon Ken Award and the 46th Photography Society of Japan Newcomer’s Award, Sunamori, while remaining torn between his three ancestral homes of the island of Okinawa, Amami Oshima and Manila, discovered a means of creating an image of the islands across which his parents and family were scattered by distancing himself and looking back once again from the past and at the same time making a connection. In 1993, Sunamori held an exhibition with the same title at the Ginza Nikon Salon and Osaka Nikon Salon that become the model for this.

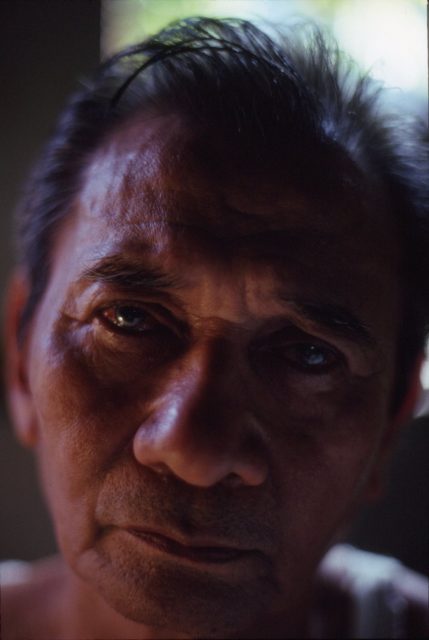

From Katsumi Sunamori Okinawa Amami Manila (1995) Sunamori’s father, upon their meeting in Manila.

From Katsumi Sunamori Okinawa Amami Manila (1995) Sunamori’s father, upon their meeting in Manila.

Hidden within Okinawa Amami Manila is the dramatic story of how Sunamori once received a letter from someone identifying herself as his younger sister, as a result of which Sunamori traveled to Manila and ended up meeting his real father. In this sense, it incorporates one of the most decisive scenes in his entire life in which the dream that had spurred him on while he “drifted” from boxing to photography is finally realized. In reality, however, his father, whom he had secretly been hoping would return from across the sea with the fortune he had made, was completely different. Despite this, this photobook, which occupies a crucial position as the finest work Sunamori ever produced, is an important factor in establishing in a story-like fashion the image of Katsumi Sunamori the photographer, who was tormented by the vicissitudes of fortune. At the same time, the “Mokushi no machi” series of photos that he was amassing around the same time while visiting the scene of the Mount Fugen disaster include works that are far removed from this image, and partly because they were made public in the “bad year” of 1995, they were never presented as a photobook and were gradually forgotten. However, I sense that it is within this very “Mokushi no machi” series that the impulse that formed the rudiment of Sunamori’s behavior throughout his life is hidden, still waiting to be deciphered. (To be continued)

The exhibition “Katsumi Sunamori – Implications of the Scenery” (guest curator: Noi Sawaragi) is on view through August 30, 2020 at the Maruki Gallery for the Hiroshima Panels in Higashi-Matsuyama, Saitama.