Katsumi Sunamori – Implications of the Scenery (1)

Katsumi Sunamori – From the series “Unzen, Nagasaki” (1993-95). © Katsumi Sunamori Photography Office.

Katsumi Sunamori – From the series “Unzen, Nagasaki” (1993-95). © Katsumi Sunamori Photography Office.

On the morning of June 2, 2019, I arrived at Nagasaki Airport and headed south by car in the direction of the Shimabara Peninsula. It was the first time I had been to the Shimabara region. My destination was the Mount Unzen area facing the Ariake Sea. The area is known as the scene of a large-scale pyroclastic flow occurring at 4:08 pm on June 3, 1991, resulting in the deaths of 40 people with a further three missing but presumed dead, as well as extensive damage to housing. The volcanic activity at Mount Unzen-Fugen that triggered the large-scale pyroclastic flow began on November 17, 1990 following a precursory earthquake swarm in 1989 centered west of the Shimabara Peninsula in Tachibana Bay, where there is a magma chamber directly beneath the seabed. In May 1991, magma began gushing forth from the side of the mountain closest to Mount Fugen, with the first pyroclastic flow occurring on May 24. But even in Japan, one of the world’s leading volcanic zones, it is unusual for a single person to witness volcanic activity on such a scale in their entire lifetime, and it would be difficult to say that the terror of volcanoes has been properly communicated to people. Now we know that pyroclastic flows can easily reach speeds of 200 kilometers per hour, and that the internal temperature of pyroclastic surges (in which hot gas and volcanic ash flow together at high speed) can reach 1000 degrees. Moreover, at its furthest point, the pyroclastic flow at Mount Fugen travelled as far as 5.5 kilometers from the collapsed lava dome. Those who try to escape such a phenomenon after noticing it stand little hope of surviving.

The Mount Unzen-Fugen “fixed point.” Photo (and all hereafter): Noi Sawaragi.

The Mount Unzen-Fugen “fixed point.” Photo (and all hereafter): Noi Sawaragi.

Despite this, the theory that it is possible to survive pyroclastic flows by maintaining a low posture went unchallenged, and competitive reporting took precedence over life-preserving behavior, with the result that many of the victims swallowed up by the pyroclastic flow were journalists and other media representatives (16 of whom were caught up in the pyroclastic flow) covering the event. At the time, because it was where so many media representatives had set up cameras and so on, this most dramatic location was called the “fixed point” (or sometimes “head-on”), and today it is where a white pyramid stands identifying it as the place people go to to console the spirits of the dead, and where every year at 4:08 pm on June 3 a memorial service is held. In Shimabara, this same day is called the “day of prayer.” Offerings of flowers are made at Nitadanchi Daiichi Park, where there is a monument to the victims, flags are flown at half-mast and a minute’s silence observed at the sound of a siren. As well, in order to pass on memories of the disaster to following generations, a concert involving local high school students is held at Gamadasu Dome (the Mount Unzen Disaster Memorial Hall), which faces the Ariake Sea and overlooks Mount Unzen’s highest peak, Heisei Shinzan. One thousand candles bearing pictures drawn by local elementary school children are lit in a ceremony held outdoors at the same venue.

Remaining foundations of the Kitakamikoba Agricultural Training Institute, and memorial bell erected on the site.

Remaining foundations of the Kitakamikoba Agricultural Training Institute, and memorial bell erected on the site.

View of “prayer candles” to be lit at night outside the Gamadasu Dome in memory of the victims.

View of “prayer candles” to be lit at night outside the Gamadasu Dome in memory of the victims.

On June 3, the day after I arrived in Shimabara, I joined others in visiting the places where memorial ceremonies were being held at the “fixed point,” Nitadanchi Daiichi Park and Gamadasu Dome and observed a minute’s silence at the appointed time. In addition, at a location some 300 meters down the mountain from the “fixed point” which I had visited in advance, the foundations of the Kitakamikoba Agricultural Training Institute where members of the local fire brigade, many of whom became victims of the pyroclastic flow, were stationed at the time, as well as the remains of the fire trucks and police cars that were suddenly caught up in a pyroclastic surge and burned beyond recognition, are preserved. The remains of other structures that were damaged in the disaster can also be seen here and there within the same area, while the remains of several houses that were buried in the lahars that occurred frequently when the volcano was erupting have been moved to the Dosekiryu Hisai Kaoku Hozon Park, where eleven are on display (eight outdoors and three indoors). At the same time, a roadside rest area has also been established inside the park in an effort to combine tourism with education [previous examples of the retention of disaster-affected houses as “remnants” of disasters include the former village of Yamakoshi in Niigata Prefecture (now part of the city of Nagaoka), where houses hit by a landslide in the 2004 Chuetsu earthquake are preserved], serving as an example that should be referred to when considering the difficult question of whether disaster remains should be retained (ie, memories passed on) or not (ie, not prolonging trauma), something that is often the subject of debate in the case of the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami.

Dosekiryu Hisai Kaoku Hozon Park

Dosekiryu Hisai Kaoku Hozon Park

On the “day of prayer” only, the gates at the “fixed point,” which is normally treated as a hazardous location and off-limits to the public, are opened and anyone may enter. What becomes clear upon actually setting foot on this site is that the “fixed point” is one of only a handful of pieces of flat land in an area where slopes leading up to the hillside continue, making it perfect for setting up a camera, and also how, because it was just a few hundred meters back from the “frontline” where volcanologists from overseas were carrying out their own observations and video recordings, it was mistakenly judged to be safe. Based on this, the volcanologists that had arrived at the site, and in particular the French husband and wife team of Maurice and Katia Krafft, who were known for approaching erupting volcanoes to record and film seemingly without fear of losing their lives, were later criticized for not alerting the journalists of the danger. But Maurice was the kind of person who, in order to record the eruptions that were occurring intermittently at Stromboli, one of Italy’s most famous volcanoes, leaped into the crater when he judged the eruptions had subsided and luckily escaped just before (seven minutes) the next eruption. He was also the kind of “crazy” scientist who is reported to have said that when he died, “I want it to be at the edge of a volcano” as if it were his dream. Perhaps one could say the reporters should have communicated among themselves beforehand to establish what kind of researchers the pair were and examined matters surrounding this more carefully.

However, even this supposedly lucky husband and wife lost their lives, bespeaking how difficult it is to avoid danger at close range at the site of a volcanic eruption. I first heard about these volcanologists, who might more accurately be described as outsider artists, in connection with a visit to the Masao Mimatsu Memorial Hall at the foot of Showa Shinzan in Hokkaido. Mimatsu was an amateur volcanologist who left behind what is probably the only record of the eruption activity of Showa Shinzan during the war, as well as a large number of nihonga depicting this activity. He also had a considerable influence on the nihonga artist Tamako Kataoka, also known for her paintings of various volcanoes around Japan. It was at the Masao Mimatsu Memorial Hall that I learned that the Kraffts had also visited the area. I wrote about Kataoka and the Kraffts in a chapter in my book Autosaida ato nyumon (An introduction to outside art) (Gentosha, 2015), so I will refrain from going into further detail here, but it was my experience in Hokkaido that made me want to go to Mount Unzen, in which sense it was the initial trigger of this visit.

However, I was not able to realize this trip for a long time, and it was after learning by way of a coincidental encounter of the existence of a photographer who had continually photographed the Mount Unzen disaster area that I was eventually able to make up my mind to do it. Among photographs dealing with this area, those taken by journalists showing how things looked directly after the pyroclastic flow and documentary material maintained by public institutions exist in relatively large numbers, but I know of no other photographer who continually photographed the Shimabara disaster area. This disaster occurred before both the 1995 Great Hanshin earthquake and the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami at a time when photographs of disaster areas themselves were rare. Nowadays they are numerous, and in the case of the Tohoku disaster in particular, many famous photographers have visited the various stricken areas to take their own photographs. However, at the time of the Heisei eruptions at Mount Fugen, such a way of thinking itself was not yet widely appreciated, and it would be true to say there was a great deal of hesitancy around outsiders going out of their way to take photographs of disaster areas for the purposes of their own expression. Given this, why did this photographer go so far as to continue photographing the Mount Unzen area amid the maelstrom of the disaster when there was still a danger of pyroclastic flows and lahars? Among the journalists killed near the “fixed point” was a freelance photographer who was providing shocking photographs of the scene to some of the weekly pictorial magazines that were so popular at the time. The photographer I am writing about in this series of columns, Katsumi Sunamori, may very well have become another victim of this disaster.

Before I continue, however, I need to explain in a little more detail about the so-called Heisei eruptions, the volcanic activity at Mount Unzen the first signs of which appeared in 1989. This eruption activity during the Heisei era can broadly be divided into two periods. Specifically, it can be divided into two periods of large-scale lava emission accompanied by the formation of a lava dome (in the local area, it is still said that the term “lava dome” was coined because the shape of the feature resembled Tokyo Dome, which had only just opened in 1988 and was a topic of conversation), with the eruption activity overall lasting for as long as four and a half year until the cessation of the emission of lava was at last confirmed in February 1995 (an announcement proclaiming the end of the eruption activity was made in June 1996). Because the large-scale pyroclastic flow of June 3, 1991 coinciding with the first of these two periods that cost so many lives was covered so dramatically in the media, people mistakenly believe that there was just a single large-scale disaster, but in fact during the second period in June 1993 there was also a large-scale pyroclastic flow that killed one person. Also during this period, whenever it rained, volcanic ash that had accumulated on the mountain turned into lahars that descended without warning, following the Mizunashi River and repeatedly assailing houses and other buildings along its course.

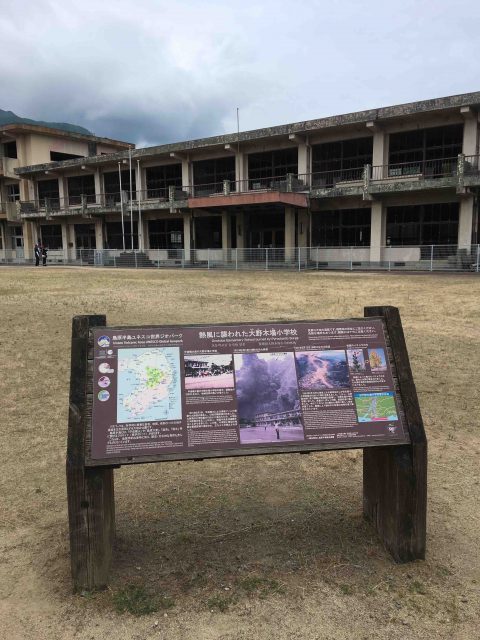

So the Heisei eruptions were a complex, large-scale natural disaster extending over a long period of time and also rare in historical terms. The person who showed us around during my visit, Shigeo Hasegawa, lost two fellow firefighters in this disaster and was forced to live away from home as a refugee for six years. Large earthquakes and tsunami do not strike the same location for years on end, in which sense volcanic eruption disasters are quite different. Astonishingly, there were 9432 pyroclastic flows during the period in question and as many as 2511 buildings damaged, and while the lava dome given the name Heisei Shinzan (a natural monument standing 1483 meters tall), which ultimately overtook Mount Fugen to become the highest peak of the Mount Unzen volcanic group, is currently in a stable condition, there is still the risk of a large-scale collapse due to earthquakes or torrential rain. If this were to happen, an amount of rock large enough to fill Japan’s largest baseball dome, PayPay Dome, around 53 times over (one hundred million cubic meters) would hurtle down the mountain at a maximum speed of around 70 kilometers per hour, reaching the Ariake Sea in just seven minutes. The surrounding area is still designated a “hazard area” in which entry is tightly restricted, as is the area around the above-mentioned “fixed point,” and monitoring by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport is continuing. The base for this monitoring is the Onokoba Mudslide Prevention Mirai Museum, where the ruins of the former Onokoba Elementary School, which suffered major damage in a pyroclastic flow, are also preserved and open to the public (though the interior is not) as a reminder of the disaster.

Preserved ruins of the former Onokoba Elementary School, which suffered major damage in a pyroclastic flow.

Preserved ruins of the former Onokoba Elementary School, which suffered major damage in a pyroclastic flow.

I am writing on and on as if I had already known these things, but until I actually went there myself I knew nothing at all about the precarious situation the region is still in today, as we transition from the Heisei to the Reiwa era, more than thirty years after Heisei Shinzan (the lava dome) at Mount Unzen erupted. As well, my knowledge was so lacking that I firmly believed that the first time a tract of land imposingly titled a “hazard area” that could not easily be entered by anyone made an appearance on our shores was when TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant suffered a severe accident at the time of the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami and disseminated vast amounts of radioactive material. Neither did I know that, because they were in hazard areas that no one could enter, the restoration of the areas covered as far as the eye can see in ejecta from the volcano and rendered uninhabitable as residential neighborhoods by raising embankments with a maximum height of six meters and maintaining debris barriers was done using independently developed unmanned construction technologies. Similarly, I was unaware that these areas were later inspected by officials from the Sanriku region and other parts of Tohoku as they sought to recover and rebuild following the earthquake and tsunami, serving as pioneering examples of work that was actually carried out in a disaster area. When I looked at it this way, I thought I finally understood that the great volcanic disaster at Mount Unzen symbolized the Heisei era that followed, which was in many ways an age of disasters, coming before all the others and thereby serving as an omen warning us in advance of the frequent occurrence of natural disasters up till the present.

In fact, as indicated by the fact that the first signs of the eruption activity at Mount Unzen appeared in 1989, the first year of the Heisei era, in contrast to the late Showa era, the Heisei era was one in which natural disasters were conspicuously frequent. Given the scale of the damage, my memories of the massive earthquake that struck in the west of the country in January 1995 are still strong, and while the disasters that occurred before that tend to pale in comparison, after the eruption activity at Mount Unzen that began in 1989 and the large-scale pyroclastic flow that occurred at the same location in 1991, there was the earthquake off the southwest coast of Hokkaido in July 1993, which was extremely large for a quake in the Sea of Japan and left 202 people dead and 28 missing and triggered a massive tsunami that struck the coastal areas of Okushiri Island near the quake’s epicenter, destroying villages and killing 168 people, the equivalent of four percent of the island’s population. As well, the same year, due to the record lack of sunshine during the summer, the rice-growing areas of the Tohoku region were hit by a poor harvest of historic proportions, halting the supply of Japanese-grown rice to eastern Japan in particular and requiring rice to be hastily imported from overseas to cope with the shortage, giving rise to a disaster that would probably have developed into the equivalent of the “great famines” of the Edo period.

It was around this time that Sunamori traveled to the disaster area at Mount Unzen for the first time to take photographs. Moreover, in August 1995, when he unveiled the results of his efforts at Shimabara by way of a solo exhibition, the country was still in a tumult following the Great Hanshin earthquake in January that year and the unprecedented event just two months later in which the chemical weapon sarin was released on the Tokyo subway early in the morning, resulting in the deaths of many people. Sunamori’s exhibition was titled “Mokushi no machi” (Town of Revelation) and was held at the Ginza Nikon Salon in Tokyo from August 29 to September 4 before travelling to Kansai where it was held at the Osaka Nikon Salon in Osaka from November 2 to 14. It included a total of 103 works presented as 457 x 560mm prints, but given they were on display in Tokyo for just a week, it is uncertain how many people actually got to see Sunamori’s photos.

But it was in May 1993, nearly two years after the large-scale pyroclastic flow, that Sunamori travelled to Shimabara to take photographs for Ashita, a magazine that covers issues related to local government. Mount Unzen had started actively emitting lava for the second time in February that year, and the city of Shimabara was once being tormented by pyroclastic flows and lahars. However, the scenes Sunamori witnessed at the disaster site made an impression on him, and he returned again and again in a personal capacity outside of work and continued taking photographs. In other words, he could have made public the results of his work earlier than his solo show in 1995, which was a full two years after this. So why was the presentation of his work delayed until this historically rare “bad year”? Of course, one can imagine how difficult the task of photographing in Shimabara must have been. At the same time, however, it is perhaps not unthinkable that the terrible disaster in the Kansai region hastened the presentation of his photographs of the Mount Unzen disaster site. There is also the possibility that, seeing as it was in February 1995 that it was confirmed that Mount Unzen was no longer emitting lava, it was after ascertaining this that arrangements for exhibiting the photographs were put in place. There was no precedent for someone presenting in public under their own name photographs of a disaster site, so perhaps consideration was given to the feelings of those directly affected. Ironically, however, the halt in the emission of lava in February came the month after the Great Hanshin earthquake. It is not difficult to imagine that in the back of Sunamori’s mind, his sense of relief that the volcanic activity at Shimabara had ceased and the disaster that had just occurred in the Kansai region became entangled.

In the end, just like the volcanic activity at Mount Unzen, Sunamori’s “Mokushi no machi” gradually faded from people’s memories. In fact, neither was “Mokushi no machi” turned into a photobook. As for Sunamori himself, he is known firstly as the photographer who won the Domon Ken Award for his only full-scale photobook, Okinawa Amami Manila, which saw him wander between Okinawa, the Amami Islands and the Philippines while questioning his own identity. He is also the photographer responsible for Okinawan Shout, which depicted the contradictions of the island of military bases through the people who live there, and Kama Tida: Osaka Nishinari, which saw him live for an extended period in Kamagasaki in Osaka in order to capture the area on film. Of course, this in itself is not wrong. However, Sunamori later developed cancer and died in 2009 at the age of just 57. Which means we can no longer ask him the real reason why he was so concerned about the Mount Unzen disaster area. Neither did he leave anything behind in writing concerning this. And so this series of columns is an attempt to reconsider from a critical perspective the significance of this based on my encounter with Sunamori, whom I came to know about almost by chance. (To be continued)

Bibliography

Endo, Shusaku. Silence (Chinmoku. 1966.) Trans. William Johnston. Peter Owen, 1969.

(The below all in Japanese)

Koho: Shimabara Unzen-Fugendake funka saigai tokushugo. City of Shimabara, 1992.

“Mizu to midori yutakana furusato no fukko o mezashite 2001-nen jigyo gaiyo.” Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transportation and Tourism; Unzen Restoration Work Office, 2001.

Oshima Hiroshi. “Photobook review: Sunamori Katsumi Tadayou shima tomaru mizu (Creo).” Network Museum and Magazine Project. April 15, 1998.

Shiraishi, Ichiro. Shimabara taihen. 1985. Bunshun Bunko, 2007.

Sunamori, Katsumi. Kama Tida: Osaka Nishinari. IPC, 1989.

Sunamori, Katsumi. Okinawan Shout. Chikuma Shobo, 1992.

Sunamori, Katsumi. Tadayou shima tomaru mizu. Creo, 1995.

Sunamori, Katsumi. Okinawa kibun. Futabasha, 1998.

Sunamori, Katsumi Scandal wa osuki? Mainichi Newspapers, 1999.

Sunamori, Katsumi. Okinawa Stories. Sony Magazines, 2006.

Mainichi Graph Special Edition: Unzen/Fugendake Zenkiroku. Mainichi Newspapers, 1992.

Sunamori, Kazura. “Unzen-Fugendake saigaishashin kara yomitoku Sunamori Katsumi no realism.” Self-published, 2019.

Sunamori, Kazura. “Shashinka Sunamori Katsumi ga mitsumeta Kamagasaki no taiyo.” Self-published, 2020.

The Catastrophe in Shimabara. Ministry of Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transportation and Tourism; Kyushu Regional Development Bureau; Unzen Restoration Office, 2003.

Note: Katsumi Sunamori’s writings, including the titles, have been extensively revised and rewritten between their initial publication as books and reprinting in paperback editions. This is one of the characteristics of Sunamori’s writing (he apparently he kept copies of his writings, including unpublished texts, at hand, and continued to revise them right up until his death). A writing style rarely seen in photographers, it provides important insight into the man Katsumi Sunamori.

The exhibition “Katsumi Sunamori – Implications of the Scenery” (guest curator: Noi Sawaragi) is on view through August 30, 2020 at the Maruki Gallery for the Hiroshima Panels in Higashi-Matsuyama, Saitama.