Escape plan from repetitive theatrics:

“SPACE PLAN: Avant-Garde Art Collective in Tottori 1968-1977”

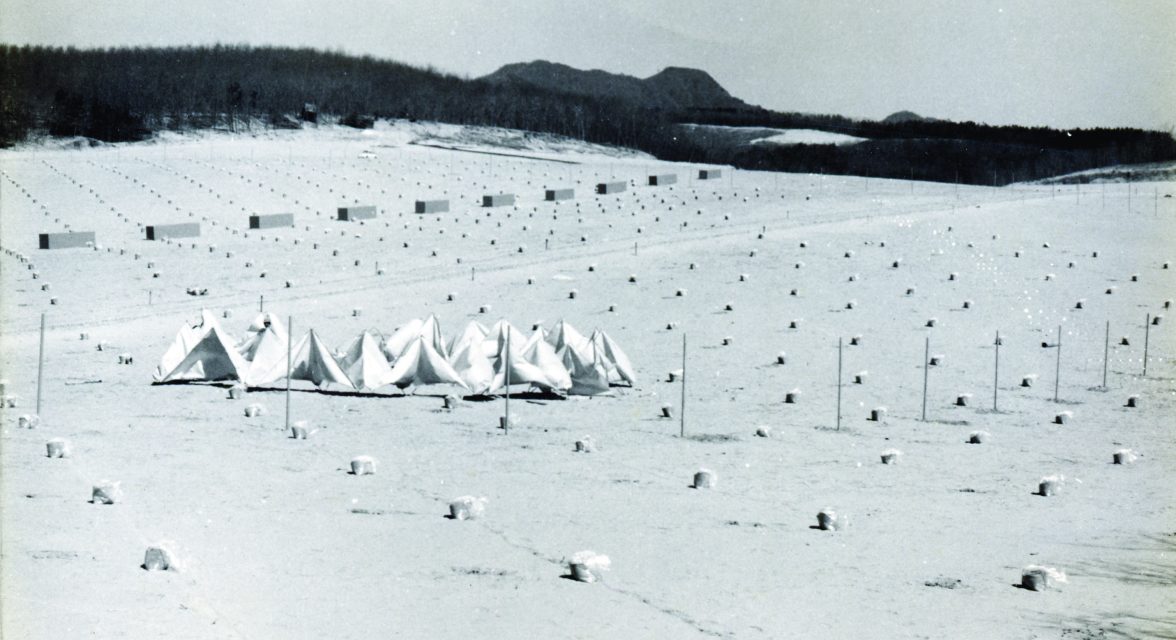

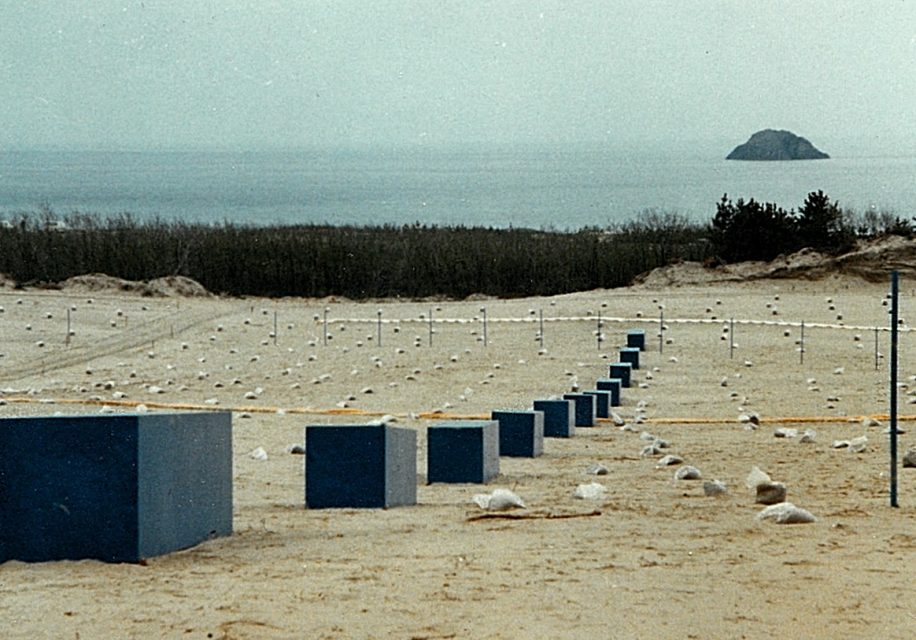

Installation view of Space Plan’s second exhibition, Tottori sand dunes, 1969.

Installation view of Space Plan’s second exhibition, Tottori sand dunes, 1969.

Because last year, 2018, marked fifty years since 1968, there was a succession of publications and exhibitions looking back on the events of that year. That they ended up being more than mere anniversarial retrospection is none other than because when we think about the passage of time that covers the period around 1968, we feel a peculiar sense of the present hanging over it. The reason for this being the recurrence of the Tokyo Olympics. Despite various differences in the social background, there is no avoiding comparisons being made in various senses between the Tokyo Olympics held in 1964 and the Tokyo Olympics due to be held in 2020. To say nothing of the fact that last year was also when it was decided that the Osaka Expo will be held for a second time, which was the last thing anyone expected.

This recurrence – farcical to say the least – has provided us with a viewpoint concerning 1968, the eve of the previous Osaka Expo in 1970, according to which it is also possible to position the present as the eve of the next Osaka Expo, just around the corner in 2025. Helped by the fact that its very existence was almost completely unknown, the subject of the exhibition that I am about to discuss, “SPACE PLAN: Avant-Garde Art Collective in Tottori 1968-1977,” has the appearance of a completely unknown, new group that has come onto the scene just six years out from the 2025 Osaka Expo, despite it being an exhibition based mainly on records of past exhibitions. In thinking about Space Plan, I feel a strong need to not simply dig up the past but to connect it to the present, whose consequences are unknown given the uncertain nature of the times.

Installation views of “SPACE PLAN: Avant-Garde Art Collective in Tottori 1968-1977,” Bird’s Gallery Tottori, 2018. Photos Rintaro Unno (top), Hiroki Tsutsui (above).

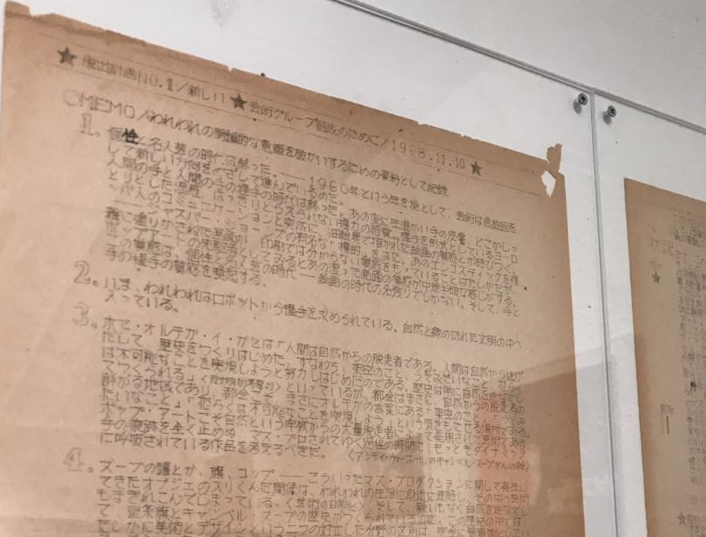

Installation views of “SPACE PLAN: Avant-Garde Art Collective in Tottori 1968-1977,” Bird’s Gallery Tottori, 2018. Photos Rintaro Unno (top), Hiroki Tsutsui (above). The manifesto “Escape Plan No. 1/For the Formation of a New Art Group” (November 10, 1968) displayed at the exhibition.

The manifesto “Escape Plan No. 1/For the Formation of a New Art Group” (November 10, 1968) displayed at the exhibition.

It was in none other than 1968 that the seeds for Space Plan (founded by Kensaku Iwai, Takashi Taniguchi, Morito Fukushima, Takehiko Funai) were sown in the ground of Tottori. The manifesto unveiled that year, “Escape Plan No. 1/For the Formation of a New Art Group,” begins with the statement, “The age of individuality and virtuosity has ended,” a quote from Geijutsu no nichijoka (The Everydayness of Art) (1) by Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, formerly a member of Jikken Kobo (Experimental Workshop), who was then playing an important role in the arts program for the Osaka Expo as a driving force, and ends with the following passage, also quoted from the same text by Yamaguchi:

Art is also completely caught up within the continuous mutual changes in our environment and way of living. Amid these changes, art will no longer be bound by particular isms or particular styles. The age of isms ended with the age of abstract expressionism.

In this way, amid the mutual and continuous changes in our ways of living and environment, we will probably see the repetition of unlimited experimentation and emancipation with regard to sensations and materials. At the end of such unlimitedness, thought as completely meaningless action will likely remain in a pure form devoid of both language and emotions. This thought will be extremely light and, provided they are able to grasp it, anyone will be able to hold it in their hearts.

The emphasis in what is being said here itself has no meaning other than being one example showing how, as the Osaka Expo drew near and such tendencies as environmental art and intermedia as new (future) art forms not bound by existing conservative mediums and styles were promoted as de facto state policy, the influence of these forms reached as far as Tottori. Accordingly, if we look at it from this viewpoint alone, it is sufficient to understand the activities of Space Plan as the result of new tendencies such as minimal art that had been introduced to Japan via the US having been developed as one variation in one particular region. However, the intentions of those involved were not directed solely at practicing such new kinds of experimental art in a manner unrelated to their region “within the continuous mutual changes in our environment and way of living.” On the contrary, their manifesto continues as follows:

In hindsight, looking at the situation in Tottori, it is difficult to feel anything other than a sense of almost complete hopelessness. The authoritarianism of undersized regional painting circles, to say nothing of the collusion, the farces surrounding exhibitions that are repeated year after year. Are these our fate, processes that are unavoidable, because we live in the provinces? Perhaps we need to first thoroughly recognize and give up hope in this barren state of affairs and then bid farewell to everything that makes up this barrenness. Displaying gestures of half-hearted opposition will surely only result in us becoming birds of a feather, more tightly constricted by the fetters of antiquated ideas and the old powers. [emphasis added]

In other words, the reason why Space Plan chose new, experimental art methods was not so much because they backed the new possibilities they offered but because these methods were formulated as a “plan” to “escape” from the obstructive situation in Tottori without being shackled by the kinds of antagonistic methods that already existed (such as Group Kyushu or Neo-Dada?). And so, in order to break away from the art circle-like, ie, modern art-like, methods of presentation and authority to which they were hostile, they needed to thoroughly distance themselves from the emphasis on individual artists and artworks that lay at the heart of the values that underpinned them.

This is probably precisely why the methods of minimal art that emerge after all traces of individual expression have been bleached were summoned at the very beginning. And while the group format was chosen as the style of presentation, there were no central members and accordingly nothing resembling a clear set of principles. Similarly, as their stage for presentation, an emphasis seemed to be placed on anonymous-like “outdoor” locations (such as the Tottori sand dunes or Lake Koyama’s Ao Island). During this period, groups that practiced expression using the outdoors or the street were not unusual, but in this respect there was something about Space Plan that clearly set them apart from these other groups.

Installation view of Space Plan’s second exhibition, Tottori sand dunes, 1969.

Installation view of Space Plan’s second exhibition, Tottori sand dunes, 1969. Work for “Camera Report,” Iwado Coast, 1976.

Work for “Camera Report,” Iwado Coast, 1976.

In fact, the thing that surprised me first of all upon learning of the existence of Space Plan was its name. Space Plan – what a mediocre title. It gives barely any indication of what the group is about. Compared to the highly individual names of contemporaneous avant-garde groups in other regions, such as Group Genshoku (Tactile Hallucination Group) or Shudan Kumo (Spider Group), how boring it is. However, it, too, seems to have been chosen as a result of giving priority to Katsuhiro Yamaguchi’s above-quoted statement, “thought as completely meaningless action will probably remain in a pure form devoid of both language and emotions.” So there was a certain reason behind it and it also differentiated the group from the avant-garde in other regions. Because the matter at issue was that they needed first of all to “bid farewell” to the very heat associated with the projection of the ego (leadership) and groups (an organization is also a kind of group). In the same manifesto, Space Plan describes as follows the composition of their actual activities:

Accordingly, the group has no specific leader. The group’s members act using pure thought and fresh ideas as their catalysts. […] As well, in order to render the group’s activities diverse and broaden and deepen their possibilities to the fullest extent, we actively promote the participation of specialists in various fields (architecture, engineering, chemistry, music, etc).

The images/artworks and the “vision” that underpins them are cultivated through the constant repetition of a tabula rasa as individuals and a group . . . , thereby promoting the discovery of fresh “themes.”

Individuals/we shy away from becoming characterless, but we aim for artworks that are impersonal.

In the final sentence in particular, the distinguishing characteristics of this group are clearly revealed. One must avoid being characterless, but at the same time aim to be impersonal. What does this actually mean? Here I see the Tottori sand dunes as the non-place they chose as their stage under these circumstances. Sand dunes are by no means characterless. On the contrary, they are an extraordinary, peculiar place. But despite this, it is extremely difficult to specify exactly what sand dunes are. Because sand dunes are always changing moment by moment. In this sense, there is nothing as impersonal as sand dunes. As well, speaking theoretically, because they are made up of countless grains of sand, sand dunes have a pluralistic nature. In this sense, the term “sand dunes” is also the name of a group, as it were. Given this, there is nothing closer to the spirit of Space Plan.

And yet they did not use this in the naming of their group. They named it simply Space and Plan, incorporating this sand dune-like nature. The sand dune environment is harsh. It was inevitable that the artworks they installed there would be assimilated by the sand dunes in no time at all. However, even this was not a failure. Despite their peculiar nature, are not these very sand dunes – an impersonal, expressionless non-place that homogenizes everything – the actual space (or, to use the term they later adopted as their name, the “abnormal space”) where they ought to have carefully made plans and assimilated as a group? Remaining true to their own vision, they simply called this a “space plan.”

Group photo of Space Plan at their 13th exhibition, Tottori Civic Hall, 1977.

Group photo of Space Plan at their 13th exhibition, Tottori Civic Hall, 1977.

Despite their variegated, energetic and sustained activities, Space Plan remained largely unknown as an avant-garde art movement for half a century. Might not one of the major reasons behind their not being unearthed until 2018 be this very naming and this exhibition of a sand dune-like nature that is impersonal and mediocre but by no means characterless? If so, it would seem that this somewhat lengthy oblivion signifies that their aims were in fact partially achieved. And the fact that they have appeared before us on a new “eve” coinciding with the decision to hold a second Osaka Expo, almost as if a new group had debuted, can by no means be called a mere coincidence.

If there is something they have yet to realize it is perhaps the very regional circumstances surrounding Space Plan itself. Looking again at the above quotations, there is no noticeable inconsistency – not only with the situation in 1968, but even if we anticipate the situation in 2019. In which case, perhaps the observations that “we need to first thoroughly recognize and give up hope in this barren state of affairs and then bid farewell to everything that makes up this barrenness,” and that “[d]isplaying gestures of half-hearted opposition will surely only result in us becoming birds of a feather, more tightly constricted by the fetters of antiquated ideas and the old powers” also still hold true. In which case, now, with the Tokyo Olympics and the Osaka Expo about to recur in all their characterlessness, in response, surely we need to work out a new “plan” and devise a different “space” to see just how impersonal they can be.

“SPACE PLAN: Avant-Garde Art Collective in Tottori 1968-1977” was held at Bird’s Gallery Tottori, from December 7 through 19, 2018.

1. Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, “Geijutsu no nichijoka” (The Everydayness of Art), Bijutsu Techo, January 1968, pp. 79–87.