REFLECTIONS – THE SPACE-TIME OF MEMORY

By Natsuko Odate and Akira Rachi

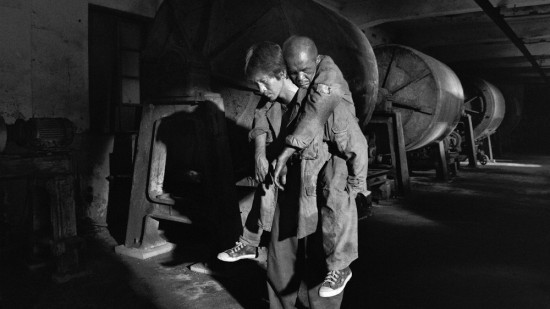

Empire’s Borders II – Western Enterprises, Inc. (2010), still. All images: Unless otherwise noted, courtesy Chen Chieh-jen.

Empire’s Borders II – Western Enterprises, Inc. (2010), still. All images: Unless otherwise noted, courtesy Chen Chieh-jen.One of Taiwan’s leading artists, Chen Chieh-jen is known for his multimedia installations and videos. He has exhibited widely across the world, including in the Taiwanese Pavilion at the 53rd Venice Biennale (2009). Recent solo exhibitions include MUDAM (2013), Taipei Fine Arts Museum (2010) and REDCAT, Los Angeles (2010). In Japan, his work was included in the 3rd Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale (2005).

Chen recently returned to Japan for the opening of the group exhibition “discordant harmony” at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, as well as to prepare a new lecture-performance in Tokyo commissioned by the independent arts organization Arts Commons. ART iT met with him in Hiroshima to discuss his work.

“discordant harmony” opened in Hiroshima on December 19 of last year and continues through March 6. Chen’s lecture-performance Realm of Reverberations (2016) was commissioned as part of Arts Commons’s Lecture Performance Series. It was presented at Shibaura House, Tokyo, for three nights from February 16-18.

Interview:

ART iT: As I was looking at the archival photographs in the work that you are showing in the “Discordant Harmony” exhibition at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, Empire’s Borders II – Western Enterprises, Inc. (2010), for some reason I started to think about the current situation in Okinawa. Even though I understand the overall work is about your history and that of your family, as well as the history of Taiwan, when I saw the documentary footage of the US military and Taiwan’s past in the video element of the work, I had the strange experience of recalling Okinawa and having tears well up in my eyes. You previously described how finding some documents and objects left behind by your father after he died was the impetus for making this work, but on the other hand the work also has a highly political aspect. How did the work develop from that starting point?

CCJ: I forget who it was, but sometime around 1970 there was a feminist who said, “The personal is the political.” There was a period when I stepped away from making works, but around the time I turned 36 I felt I had passed a certain point and started to make works again. Since then, I have come to believe that no matter how complex the problem may be, I can resolve it if I think about it seriously on my own. Doing so makes it possible to reconnect to the world from all kinds of perspectives. The act of creation relates to people, and it relates to the world, and it relates to society. It’s that simple.

ART iT: You call it simple, but on the other hand duration is another important element in your works. Maybe it’s not quite flânerie, but it’s like your thoughts are building up as you wander around and make detours without a clear objective. I have the sense that viewers virtually experience this as they watch the work. In other words, instead of reaching a conclusion, the bodily experience of slowly proceeding along a course of intellectual digressions is incorporated into the length of the work.

CCJ: I’ll give you an example. My work Factory (2003) deals with a garment factory and the women who work there, but in fact it also relates to my older sister’s life. My sister always worked at factories. As you know, these factories came to China and Southeast Asia from the US and Europe. The factories can move, but the workers are not allowed free movement. They are made to suffer under things like capitalism and imperialism. These issues are already widely known, but the really difficult problem is how these oppressed workers can raise their voices and speak about this situation. So in the case of Factory, I first met with the women and spent a year following their activities. I didn’t bring a camera or even an audio recorder. I just spoke and interacted with the women in a friendly way. And then, when all these images came floating into my head, I finally started to think about the work. The actual shooting time was no more than five days. The time I spent on filming was nothing compared to the total time I spent with the women.

So you asked about the starting point of the work, but the fact is that even I’m not sure what it is. It could be a memory from 20 years ago when my sister was working in a factory, or it could be a memory from when I myself was in the factory. The production and the project simply started without any clear starting point.

Both: Empire’s Borders II – Western Enterprises, Inc. (2010), still.

Both: Empire’s Borders II – Western Enterprises, Inc. (2010), still.ART iT: All kinds of elements related to the past, present and future emerge as the camera wanders among the objects that appear in Empire’s Borders II – Western Enterprises, Inc. How do you see the connections between these elements?

CCJ: It all comes from personal experience. For example, the “you” speaking to me right now is not just your present self. Maybe your five-year-old self, and your 10-year-old self, and even your future self – different selves from different moments – are all speaking together. I think it’s possible to see the past, present and future in the work, but it also depends on your personal experience. It’s not some difficult philosophical concept, or even a challenging problem in the first place. I imagine that many people have had similar experiences.

ART iT: But the nature of time and space in this work is different from the normal sense of time and space – in a way that is a bit uncanny. With all these similar scenes that keep repeating, or the insertions of documentary footage, it’s impossible to get a grasp of the overall temporal or spatial framework of the work, and you start to get confused about where you stand.

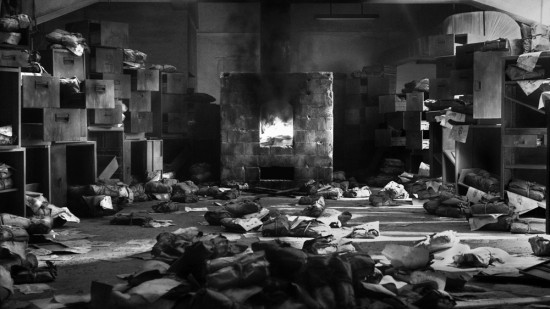

CCJ: That’s my intention. In the work there are repeated scenes of something burning in a stove. That place is a place that cannot be found by the people who appear in the work. Only the viewers can see it. [Although this time in Hiroshima it is being presented as a single-channel work,] the original installation had three screens. Two of the screens were placed behind the main central screen, almost as if they were hiding, and they showed the scenes of all these documents being burned in the stove. The people in the work keep wandering around the main screen and might never find the place where the documents are being burned, whereas all the viewer had to do is walk around the main screen to see the footage of the documents being burned one after the other.

There is another scene where the workers hold in their hands pieces of paper with numbers scrawled on them. The numbers represent the number of days they have been unemployed, but all these details that emerge in the work are left unresolved. The viewers see and recognize certain things in the work, but there are actually many things they overlook. That is, there is always a remove between the viewer and the work. Most people will read the introductory text at the start of the work and think it’s about the history of the CIA in Taiwan, but all the viewers see are the people walking around some building. Even if you were to trace that image, it has nothing to say about the history of the CIA in Taiwan.

At the end of the work all the people gather in a big room, and at first it seems as though they are unable to leave the building, but at the same time there is nothing informing the viewers about what this building might be. The last scene shows the smoke emerging from the stove, which looks a bit like a hole, but also looks like a mirror. Seeing this scene, viewers might wonder about just what was burning in the stove, or about how long it will take for the smoke to finally clear. And it is at that moment that viewers will start to think about their own situations. So the work begins with an issue that everybody knows, but as they keep watching it, viewers will start to think about their own situations.

ART iT: In fact, the relations between people and numbers appear not only in this work, but also in your work set in the sanatorium. Are you interested in the way that numbers can make individuals anonymous? Currently the Japanese government is trying to introduce a new “My Number” system that would assign all citizens and residents numbers for the aggregation and management of their personal information, so I am thinking here of the aspects of anonymization and control in the relations between people and numbers.

CCJ: Well, I guess there’s no way to escape numbers. For example, I have a Taiwanese identity card, which has a chip embedded in the back with all kinds of numbers inside it. So exactly to what extent are we represented by numbers? This kind of control extends all the way to biopolitics. And maybe art is something that can resist that. There’s a process leading to biopolitics, and art exists as a place for diverging from that process.

Taking a critical stand against biopolitics is one of the political roles of art. The political potential of art can be found there and not in talking about political issues. Normally we speak critically about issues relating to the CIA, but you could also say that speaking critically is the only thing we can do in such situations. It’s the same when we talk about the people oppressed by capitalism. So it’s almost like walking around “Western Enterprises” is the same thing as the way we walk about in our actual lives under the control of power.

Returning to the last scene with the smoke, no one knows where that smoke will go. Since the scene lasts for a while, maybe viewers will want to distance themselves from the image of the smoke and start thinking about something else, just as you said you thought about Okinawa. That moment – which is the moment something political emerges – is art. So art is not about making artworks as such, it’s about making those moments when art is created.

Above: Empire’s Borders II – Western Enterprises, Inc. (2010), still. Below: Realm of Reverberations (2014), still.

Above: Empire’s Borders II – Western Enterprises, Inc. (2010), still. Below: Realm of Reverberations (2014), still.ART iT: How about Realm of Reverberations (2014)? This work relates the stories of the different people who appear in each of its segments, and I feel that compared to Empire’s Borders II – Western Enterprises, Inc., it focuses more on the people.

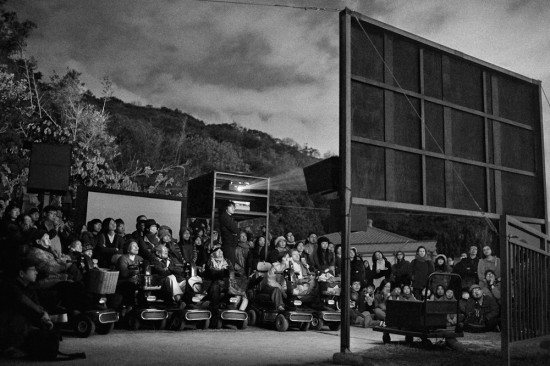

CCJ: The first time I showed the work, I did an outdoor screening at the place where we did the filming, Losheng Sanatorium. Even as the audience watched one video, the soundtracks to the other three videos were also playing. Each of the four segments is of different length, so the sounds that could be heard with each segment were constantly changing. So here, too, the moment of art is produced not by the artist but by the audience. And each member of the audience probably experiences a different moment of art. And of course there are also probably people who don’t feel that moment at all.

What is important is that the viewer herself should enter a state of deep thought, and follow her own imagination. That way, the viewer’s thoughts take on a form that is not anticipated by the artist, which I think is how it should be. For example, Realm of Reverberations deals with people suffering from leprosy, and that’s where the story begins, but after seeing all four segments, there may be some other associations that have nothing to do with leprosy that arise in the viewer’s mind.

What does it mean to create? There are four points here which all have the same pronunciation but different meanings. First you have the kiten (origin, starting point), and then the split in the road of kiten (a branch point), the mathematics of the kiten (singularity, singular point), and the vanishing or exploding kiten (initial singularity). For example, in WesternEnterprises there’s a highly restricted off-limits space, which contains the history of the past, the links between different histories, the histories of different classes, the history of contemporary workers. You could call it a “real documentary.” But in fact the viewer knows that all of this has been fabricated. All these histories have been compressed into a single divergent point, which I think viewers can sense when they see the final scene with the smoking stove. Maybe you could call it the moment of explosion. And then you go back to the beginning and repeat. That’s my work.

ART iT: Is it possible to think of what’s happening here as being related to communal memory, or collective memory? Like, instead of every single memory being individuated, all the memories are in a sense one thing. It might be hard to actually depict the collective memory that emerges among a gathering of people from different contexts, but it’s certainly possible for it to exist.

CCJ: Yes. Although in fact collective memory here does not mean that everybody has the same memories. We are all different, but we have similar memories that have points of intersection. There is no need for the viewer to know all about the histories and contexts that appear in the work. When viewers watch the work, if they have some kind of similar experience then they can connect with the work. The work is meant to confuse the viewer in the first place. It starts with a simple beginning, and then it gets progressively confusing. There are multiple points of divergence in the work, so it’s impossible to have the same experience of it.

Realm of Reverberations (2014).

Realm of Reverberations (2014).ART iT: In that sense, there are other characters in Empire’s Borders II – Western Enterprises, Inc. aside from the person who seems to represent yourself, but in the lecture-performance you will present in Tokyo in February (produced by Arts Commons), you will be speaking in your own words. Have you ever played yourself before?

CCJ: So far I have never played myself in my video works, although there was a time when I did make performances. The venue this time, Shibaura House, is a special building that is almost entirely made of glass surfaces, so it inspired me for this lecture-performance, as opposed to performance. I plan for it to have a sense of floating. The work I will perform there also starts with the story of the leprosy sanatorium, and then all these other stories will enter into it, including the problems young people in Japan have with temporary work agencies. I think in the end I myself will just be one part of the lecture-performance. Of course I will also talk about leprosy, but as all these other stories about exclusion, about bio-politics, about temporary labor enter in, I think there will be a moment where the viewers start to think about these issues in relation to their own experiences in Tokyo. So the lecture-performance is not just about Taiwan’s past, or the history between Taiwan and Japan. I am looking forward to having the viewers experience their own artistic moments for themselves.

(Cooperation: Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art)

Both: Installation view in “discordant harmony,” Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, 2015. Photo ART iT.

Chen Chieh-jen: Reflections – The Space-Time of Memory