OUT OF INFINITY

By ART iT

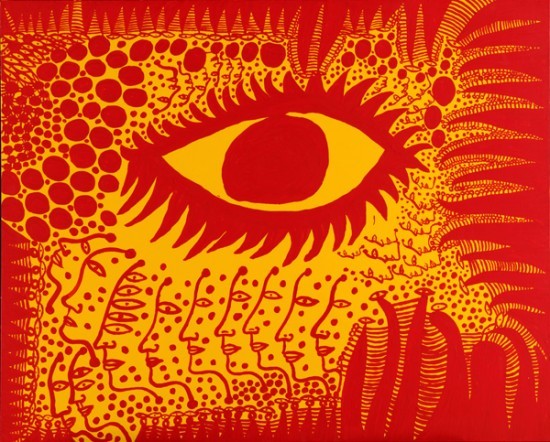

Once the Abominable War is Over, Happiness Fills our Hearts (2010), acrylic on canvas, 194 x 194 cm. All images: © Yayoi Kusama, courtesy Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo, and Yayoi Kusama Studio, Inc.

Once the Abominable War is Over, Happiness Fills our Hearts (2010), acrylic on canvas, 194 x 194 cm. All images: © Yayoi Kusama, courtesy Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo, and Yayoi Kusama Studio, Inc.ART iT: The extent of your recent activities is extremely impressive. Internationally your exhibition that began in 2010 at the Pompidou in Paris has toured to the Reina Sofia in Madrid and the Tate Modern in London, and just opened at the Whitney Museum in New York. And within Japan your exhibition that opened earlier this year at the National Museum of Art, Osaka, is now touring to multiple venues. At the same time, you have collaborated with Louis Vuitton on a new collection, and the show windows at the brand’s boutiques feature your imprint. As your works continue to proliferate across the globe, I can imagine you are extremely busy.

YK: Yes, I am incredibly busy. Even so, every day from around 10 or 11 in the morning to 6 or 7 at night, I am right here painting.

ART iT: You have said that you constantly see hallucinations and images in your head, but beyond that, from the moment you wake up do you also have an idea about what colors and materials you will use for the day’s painting?

YK: In the morning I first sit here in my studio, and although I have some sense of what kind of picture I would like to paint, once I actually start painting my hand moves faster than my head. I work my way all around the canvas as I paint.

When I am painting I am completely absorbed. It’s only after I’ve put on the finishing touches that I can see what I’ve been doing. That is the first time that I am able to objectively look at the work. In the beginning I have no vision for how the finished work will look. If you want to know more about my process, you almost have to ask my hand.

Yayoi Kusama at work in her studio, 2009.

Yayoi Kusama at work in her studio, 2009.ART iT: You gave a poetry reading at the opening of your exhibition in Osaka. As with painting, when you compose poems and write novels do the images simply spring forth?

YK: Recently I’ve been so busy I haven’t had time to work on things like poetry. However, the titles of my new works have become longer.

ART iT: Do you always title the works after they have been completed, or do you also have something in mind before you have started painting?

YK: Both cases exist for me. When I am painting I am so focused that I completely lose myself in the work. Without once even thinking about what kind of picture I would like to make, my hand moves first and my head follows behind. Once I have finished the painting, then I think, “Ah, so this is what I was up to!”

ART iT: Do you ever reflect upon your previous works?

YK: If I had such luxury of time, I would spend it all making new works. What you see here are all new works. I’ve already made close to 200 pieces in this series. After around 100 works I switched to a metallic ground. A number of pieces were included in the “Infinity of Infinity of Infinity” exhibition in Osaka.

ART iT: Will there be opportunities to see these latest works in the near future?

YK: The exhibition in Osaka toured to the Museum of Modern Art, Saitama, and is now at the Matsumoto City Museum of Art. Toward the end of the year it will continue to the Niigata City Art Museum. In Matsumoto, I added a number of these new works to the display. Next year I will have exhibitions touring in South America and Asia in which I plan to include the new works.

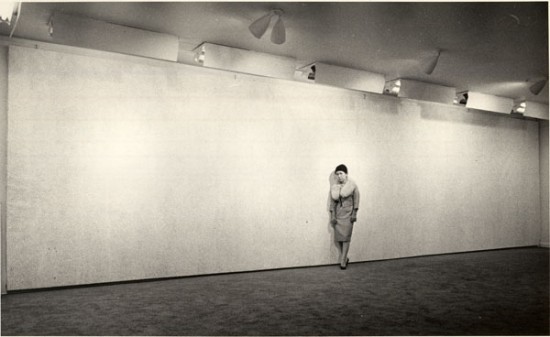

Yayoi Kusama at Stephen Radich Gallery in New York, 1961.

Yayoi Kusama at Stephen Radich Gallery in New York, 1961.ART iT: When did you first start to think about painting and the kind of messages it could communicate?

YK: From my childhood I grew up constantly thinking about such matters. At around the age of 10 I wanted to become a painter, but my family and others around me would not hear of it. Even so I managed to gain acceptance from my family, and left for a year to study painting in Kyoto. Following a return to Nagano I then developed a strong desire to go to the US.

I left for the US in 1957. At the time there were almost no people traveling there. On my flight, aside from myself it seemed as though there were no other passengers except for two GIs and a war bride.

I first arrived in Seattle and had a solo show there at Zoe Dusanne Gallery, after which I continued on to New York.

ART iT: It is remarkable that from leaving for the US through to the present, your vision for art has not wavered at all. When you arrived in New York Pop Art had yet to emerge and Action Painting was the main trend. It was in this atmosphere that in 1959 you held your first solo show in New York at Brata Gallery. I understand that Donald Judd came to see the show and bought a work.

YK: Yes. At the time Brata Gallery was located in downtown New York. Donald came to see my show and was really taken with my work. He wrote an article about me for Art News. It was from that connection that we began our exchanges. Donald and I shared a strong sympathy in our ideas about the future direction of art. When I first got to know him, he was still studying at Columbia University, under Meyer Schapiro. He was also writing on art for a number of magazines in addition to making his own paintings. He would show me his paintings and ask for my opinion, and then we would have heated discussions about art. He was a truly upstanding person. At I time when I was economically struggling, he bought a large work from me. We were both poor – I remember he had to pay me in several installments. In order to become a painter, he was looking for a large studio, and ended up moving into the space above me. The next space over from me was Eva Hesse’s studio. She had just divorced so she was a frequent visitor to my studio.

Because we were so poor at the time, both Donald and I would skip breakfast and eat only lunch. Because he had no materials for his sculptures, at night Donald would go looking around for things he could grab from roadside construction sites. Dan Flavin and I would accompany him on these trips to keep watch. Whenever we saw a policeman coming we would let Donald know, and then we would all act as if nothing were happening. Once the policeman left we would take up the work again. Dan and Donald were extremely close friends.

Then when Donald died his children established the Judd Foundation in Marfa, Texas, and the work that he bought from me sold at action for over five million US dollars. The result surprised even me, but in that sense it reflects Donald’s prescience.

Similarly, Frank Stella was another frequent visitor to my studio, and he bought the work Yellow Infinity Net (1960), which was later acquired by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

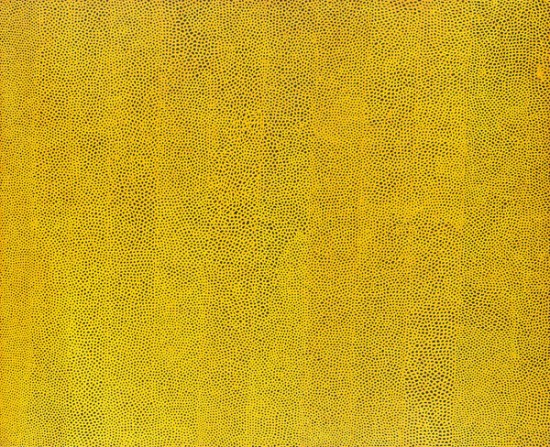

Top: Yellow Infinity Net (1960). oil on canvas, 240 x 294.6 cm, collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; purchased from Frank Stella. Photo John Bak. Bottom: Narcissus Garden (1966), installation view at the 33rd Venice Biennale.

Top: Yellow Infinity Net (1960). oil on canvas, 240 x 294.6 cm, collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; purchased from Frank Stella. Photo John Bak. Bottom: Narcissus Garden (1966), installation view at the 33rd Venice Biennale.ART iT: I also heard that when you were in Italy you were close with Lucio Fontana.

YK: In 1966 when I was invited to participate in the 33rd Venice Biennale I made an extended stay in Milan to prepare my work, and Lucio helped host me during that time.

The work I exhibited at the Biennale was Narcissus Garden. Lucio helped me to make the work and leant me the use of his studio. Moreover, when I was looking for a place to buy the mirror balls for the work, he told me where to go and gave me the money for the balls.

ART iT: From Action Painting to Minimal and Conceptual Art, Pop Art and Photorealism, you have personally lived through some of the major shifts in contemporary painting. What do you think about them?

YK: There are even people who say that I was the one who sparked off Pop Art. Photorealism came after that. There were a number of schools, but almost everybody gave it up after two or three years. I really believe that once you start something, if you do not stake your entire life on it than it’s just a hollow exercise. In that sense I believe art is a weapon for raising the capacity of humanity. Those who are unwaveringly dedicated to putting their all into the canvas and to working at it every day are the real paragons. You can tell that they make good works.

ART iT: As a female artist, you have maintained a pioneering sensitivity to social issues throughout your works to the present, but early in your career it seems like there were misunderstandings about what you were doing. Do you feel that the age has finally caught up with you?

YK: It’s true. I won’t name any names but certainly there have been cases where other artists have taken my ideas to make their works. In particular this happens with my works from when I was younger. Of course I am always one step ahead of them. Even so, it’s taken quite a while for my works to be understood. Everything around me is moving too slow. If I were to adjust what I’m doing to that speed, I would have to live another 400 years!

ARTiT: Aside from your touring exhibitions, what other projects do you currently have underway?

YK: Currently I am having a new building constructed not far from this studio. We just held the groundbreaking ceremony, and the building is scheduled to be completed around October of next year. The current studio will be used exclusively for making works, while the new building will house storage and archive facilities, although I’m undecided at this point whether to open it to the public.

ARTiT: If you did open it to the public, you could theoretically have a space to show your works exactly as you envision them.

YK: To build a museum and preserve my works for later generations who would continuously come to view them is certainly something I have thought about. The more works I make the more I plan to place there.

Joy Feel when Love has Blossomed (2009), acrylic on canvas, 194 x 194 cm.

Joy Feel when Love has Blossomed (2009), acrylic on canvas, 194 x 194 cm.ARTiT: As one of the most senior artists in Japan, is there anything in particular you wish to pass on to the current generation of young artists here?

YK: Young people all say that they want to become painters or want to become sculptors, and the most important thing is that they hold on to that spirit without any trepidation. Even those who have shining debuts might give up after two or three years, either because they end up in a different field from art or they simply stop producing. When I see such people I think that if only they had held on to their convictions to make the paintings of sculptures that they envisioned, if only they had been willing to pursue it even until death, then they could have made even better work.

I like Henri Rousseau and Edward Munch, because they are artists who stand up to the flow of time that is history. From youth they were fatally committed to painting, and that is why even though they are dead they still have followings.

When you look at compendiums of their works, you can tell that they were completely dedicated to painting. But you look at the portfolios of other artists and you can tell that they gave up somewhere. To pursue a single thing to the very end, to the extremes of your capability, is a battle. However much talent you may or may not have, if you truly commit yourself to making art, then even if your works are no good, the deep-felt conviction they manifest can still move others.

I have never once thought of giving up my art. I cannot even imagine a life without art.

I believe that the world will continue to undergo extreme changes, but even then, as I age I plan to continue making works that can touch people’s hearts and present images that are overflowing with vitality. That is why even though I try to objectively think about whether I am the best artist I can be, I have to continue making works – I have to keep painting like this, painting from morning to night.

ART iT: In your book Infinity Net: The Autobiography of Yayoi Kusama (2002), you write about how as you approach death you feel a crazed passion for making art, because you can sense that you are working under a deadline. Do you feel that the works that you want to make are still springing forth for you, and that you are able to continue painting into the foreseeable future?

YK: Yes. While I am alive I plan to make as many works as possible to leave behind for posterity.

Because I am no longer young, I have to paint as much as I can, so that after I die as many people as possible can experience the messages, the life approach and ideas about any number of events that are reflected in my works. Given the little time that remains, I have cut back the time I spend eating and sleeping, and am solely focused on painting. I have a strong desire to address and communicate with not only people who are interested in art, but with all people. Considering the course of history, there will surely be more artists who emerge in the future, but what I myself hope to do as an artist is to make the best works possible, works that can transcend things like war and terrorism and help bring about a life of peace. That is why I am so committed to painting. Then after I die, if people reflect on who I was and the works that I made, that would validate my living.

I believe that I have not yet reached the real starting point. Everyday I spend painting I think that I want to become an even better artist than I am now. Even after I die there will be people who are cheered to see my works. For an artist one of the greatest joys is to think that there are people who will admire one’s works, and ensure that they are preserved.

In this era of war and terrorism, and at a time of many crises, artists must understand the urgency for making good works. If we can make works that encourage compassionate living, then we can make clear the social necessity of art, and the art world will continue to flourish.

Yayoi Kusama: Out of Inifinity