Dan Cameron Compares Two Currents in the History of Performance Art

Two concurrent exhibitions in the New York area – Marina Abramović’s “The Artist is Present” at the Museum of Modern Art and Carolee Schneemann’s “Within and Beyond the Premises” at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art at State University of NY at New Paltz – raise some unsettling points about the way that museums contribute to a seriously lopsided understanding of the evolution of performance as a visual art medium. This comparison between the two exhibitions is not intended to pass as a critical judgment of either artist’s individual achievements, nor does it specifically analyze the curatorial efforts underlying either exhibition. Instead, my subject has to do with the power of consensus to determine museum policy, and, secondarily, an absence of institutional commitment to recognizing the historical significance of artists during their lifetimes.

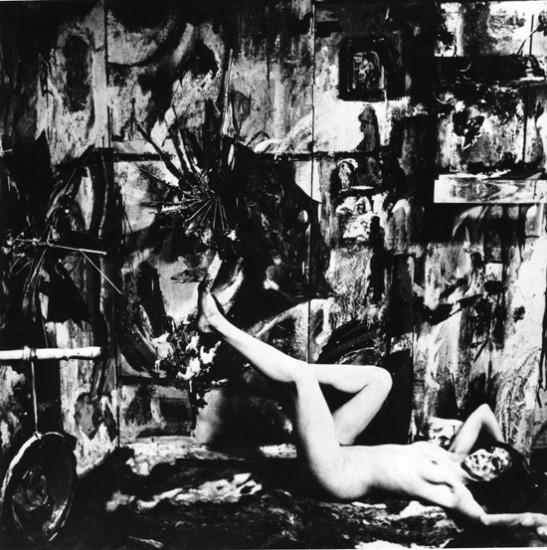

Carolee Schneemann – Eye Body – 36 Transformative Actions (1963) Action for camera. Photo by Erro. Courtesy the artist.

Carolee Schneemann – Eye Body – 36 Transformative Actions (1963) Action for camera. Photo by Erro. Courtesy the artist.A preliminary note should take into account the relative histories of the two artists in question. Carolee Schneemann, who was born in Philadelphia and is now in her mid-70s, is arguably the first artist in the world to have developed a sustained body of work using her own body as both subject and material. By 1963 she had created a series of photographs, entitled Eye Body, which document a performance created in her studio, and out of which a broad swatch of contemporary art based on photographic self-portraiture has developed. By 1965, she had created her best-known work, Meat Joy, first performed in Paris at the American Center and then in New York at the legendary Judson Dance Theater, and by the time performance art became an acknowledged discipline in the mid-1970s, she had developed a decade’s worth of activity, including Up To and Including Her Limits (1973-76) and Interior Scroll (1975), which became benchmarks for subsequent feminist-based art practice.

Marina Abramović – Installation view of the performance The Artist Is Present at The Museum of Modern Art, 2010. Photo by Scott Rudd, © 2010 Marina Abramović. Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Marina Abramović – Installation view of the performance The Artist Is Present at The Museum of Modern Art, 2010. Photo by Scott Rudd, © 2010 Marina Abramović. Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New YorkThe career of Marina Abramović, who is about 10 years younger than Schneemann, began at just about the time the latter’s presence was fading from the cutting edge of avant-garde practice. Abramović, who is from Belgrade, created performances while still an art student, although her first internationally recognized body of work was made in collaboration with her longtime companion, the German artist Ulay, centering on activities that the pair developed and performed together through the 1980s. By the mid-1990s Abramović, now working by herself, began producing works that international art curators could more easily incorporate within large-scale exhibitions, in part because her artistic evolution tended naturally toward deploying institutional structures as a means of framing her practice. Not incidentally, rather than adopt a patchwork approach to ideas taken from dance, Happenings, Fluxus and John Cage – as Schneemann can be argued to have done – Abramović invented a language and practice that is specifically adapted to the museum as public sphere and sensualist town hall of experiences and ideas. This can be considered her signal achievement.

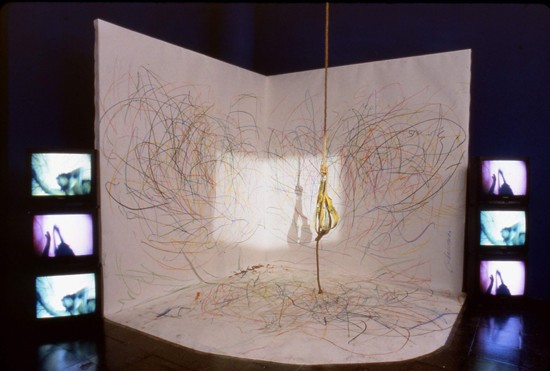

Carolee Schneemann – Up To And Including Her Limits (1973-76) Installation with crayon on paper, rope, harness, 2-channel video on six monitors, Super 8 film projection. Courtesy the artist.

Carolee Schneemann – Up To And Including Her Limits (1973-76) Installation with crayon on paper, rope, harness, 2-channel video on six monitors, Super 8 film projection. Courtesy the artist.Several biographical characteristics link the artwork of Schneemann and Abramović in other ways, including both artists’ reliance on their striking physical appearances, especially as this has been a factor in the public display of female nudity, and a deep engagement with male collaborators. Schneemann’s early partners (in life and art) include the composer James Tenney and the sculptor Anthony McCall, while Abramović has tended more toward high-profile platonic partnerships with powerful curators like Jan Hoet and Klaus Biesenbach. In Schneemann’s case, vast swaths of her messy oeuvre are tangled up with her romantic involvements with others – either her men or her cats – and as a result it should not be surprising that the only major tome to date on her work, Up To and Including Her Limits (1996), was self-published. Perhaps also unsurprisingly, virtually no important works by Schneemann can be found in the collections of any major US art museums, and her last survey exhibition, which I organized, took place in 1996 at the New Museum in New York. By contrast, Abramović’s current survey comes only a few years in the wake of an equally successful performance event at the Guggenheim, 2005’s “Seven Easy Pieces,” and for her, the passionate commitment of a handful of curators has resulted in her being positioned front and center of an artistic pantheon in which some of the essential artistic questions of our time are those that she herself was the first to pose.

Marina Abramović – Nude with Skeleton (2002-05) Black-and-white photograph, 125 x 145 cm. © 2010 Marina Abramović, Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Marina Abramović – Nude with Skeleton (2002-05) Black-and-white photograph, 125 x 145 cm. © 2010 Marina Abramović, Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.It is at this point that I feel the need to break with conventional wisdom in my field. Instead of treating Abramović as if her practice evolved independently of already-existing tendencies in body and performance art, wouldn’t a better contribution to art history be to articulate her role within a larger historic trajectory of performance, and specifically body art, especially if that genre happens to include a number of major practitioners whose art is still unfolding before our eyes? I’m singling out Schneemann not simply because she is older and an obvious pioneer of certain principles that Abramović and others have employed to greater acclaim, but for a deeper reason: I consider the underestimation of Schneemann’s work to be one of the most egregious art-crimes of our era. I find it incomprehensible that an artist whose influence is so broad and far-reaching should continue to struggle for visibility, at the same time that a vast critical sphere seems to have opened up for those who have adapted her ideas for a dramatically different time and place.

Having established this imbalance in explaining why the artist who was one of the inventors of the medium in which both work has been relegated to a nearly invisible retrospective at a relatively small university gallery in upstate New York, while her successor’s exhibition fills the fabled halls of the most prestigious modern art museum in the world, attracting extraordinary media attention, I would suggest that now the real work should begin. Instead of passively accepting a telling of recent art history in which Abramović’s accomplishments appear sui generis, my proposal is to undertake a more comprehensive history of performance art – especially feminist-based performance art – in which the most prominent actors are acknowledged for their contributions. Perhaps we are still somewhat in the thralls of the excitement, aesthetic and otherwise that was first generated a few decades ago, when female artists determined that removing their clothes was one way to throw off the straightjacket of a male-dominated art history. But that happened in the 1960s, not the 1970s or ’80s, and if we are to ever do justice to the critical and philosophical ramifications of this still-unfolding development in the art of our time, we could start by giving credit where credit is due.