Hu Fang is a fiction writer and co-founder of Vitamin Creative Space, Guangzhou, as well as The Pavilion/the shop, Beijing. What follows are his “Things Worth Remembering” for 2010, Every Day Except Christmas:

January: Miracles that slip through the cracks

I spoke with a sound artist and amateur musician who told me that when he enters a certain space, he is able to subconsciously feel that space, and anticipate what will occur there. He likes to play at table magic, the kind of tricks that even at an intimate distance can produce a sense of wonder (making miracles happen right before your eyes!). In the course of our conversation, I realized a sense of the miraculous can actually emerge from “interstices”: between different individual sets of expectations and the spaces between different bodies and different sensibilities, “miracles” always slip through the cracks.

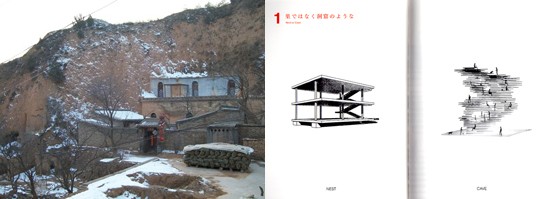

February: Nest or Cave

A Shanxi cave dwelling next to Primitive Future

A Shanxi cave dwelling next to Primitive FutureReceiving some photographs of cave dwellings that a friend of mine took on a visit home to Shanxi for Chinese New Year, I suddenly realized that a “cave dwelling” is no different from a “cave” as described by the Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto. For me, this is an architectural form that can reclaim the earth, a new architectural potential that can respond to the planet’s gravity and reconcile it with human processes of perception. Fujimoto has called exactly this new discovery of mine as “the discovery of primitiveness”

Through the comparison of the Corbusian “nest-like house” and what he considers to be even more archetypal, the “cave-like house,” Fujimoto imagines in his thesis “Nest or Cave” a schematic for a “Primitive Future.”

If the “nest-like house” is a functionally designed space in which people must adapt to and rely upon a predetermined functionality of space, then the function of space in a “cave-like house” can be explored and defined by that space’s inhabitants, who are stimulated to discover their own accidental uses for the space. The cave-like house becomes a form that precedes the nest-like house.

Is not the “cave dwelling” the “primitive future” of Chinese living?

Image credit: Left: photo Michael Eddy. Right: spread from Sou Fujimoto: Primitive Future (Inax, Tokyo, 2008).

March: Non-historical time

I suddenly recall the generosity of Romanian artist Ion Grigorescu’s angelic grandson. When we first met him in Bucharest, he was not yet 10-years-old. Leading us into the elderly artist’s dark and barren room, he fingered the bookshelf and said, “These are my grandfather’s books, but they aren’t related to historical time; they are about the seasonal time of spring, summer, fall.”

He told us he hoped to visit the Great Wall of China so that he could verify everything he had read about it in books, and he hoped that the trees in front of the house would mature quickly, because, “they do not belong only to me.”

April: If on a spring day you encountered a mist indoors

Olafur Eliasson

Olafur EliassonThis time, you entered the work’s interior, or, as concerns the artist Olafur Eliasson, it is because you entered it that this work finally came into being.

Upon entering the space, you are immediately immersed in mist, which makes you recall the feeling of passing through the smog of the city. Wrinkling your brows, you somewhat apprehensively sniffle, and as you move, attempt to eradicate your perceptual confusion while also attempting, through observing the movements of the people around you, to regain your orientation. This time in which you explore space through your own perceptions ultimately becomes a new horizon.

Perhaps returning to your memories of reality can enable you to revisit this site that you have already departed, just as Olafur previously has said: the distance it takes to enter and leave the exhibition is equally far.

Image credit: Installation view of Olafur Eliasson and Ma Yansong, “Feelings Are Fact,” at Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing, 2010, photo Hu Fang.

May: Life & Death in Venice

Ming Wong

Ming WongIn 1912 Thomas Mann published his novella Death in Venice; in 1971, that novella was adapted into a film of the same name by Luchino Visconti; and 29 years after that, the Singaporean artist Ming Wong made the three-channel video installation Life & Death in Venice (2010), based on Visconti’s film.

In his work, Ming Wong simultaneously plays the film’s two main characters, the elderly artist Aschenbach and the beautiful youth Tadzio. Ming Wong’s video retains the essential plot of Visconti’s film: in surreptitiously gazing at the youth, Aschenbach flounders in his own dangerous and hopeless search for beauty; the youth’s gesture of raising his finger to the sky becomes the death knell that rings for Achenbach’s life. In Ming Wong’s video installation, time and space once again become indeterminate elements that both call into question and also provoke viewers themselves to enter the endless cycle of desire and separation.

Image credit: Installation view of Ming Wong, “Life and Death in Venice,” 2010, photo Hu Fang.

June: Chairless

This “chair” is actually something like a cummerbund. When it is wrapped around the user’s legs and back, it becomes a chair that is both a chair and yet not. One’s own legs become the chair legs, one’s own back the chair back. From the chair’s diagram one can clearly see how the body itself can be transformed into a chair: it is an application of the philosophy of Zhuangzi.

Commissioned by Vitra, the Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena’s Chairless is the design that has made the deepest impression on me this year.

Image credit: Photo Hu Fang.

July: The most beautiful school

School and home

School and homeAnything but a dream, my trip to northeast China in July provided me the chance to see the most beautiful school ever. Perhaps few people are even aware how much growing up here benefits from the gifts of nature. And how would anybody report on this situation anyways?

It is said that the area around the school will soon be developed, but aside from development, what else is there for us to do?

Looking at Taiwanese architect Wang Ta-hung’s 1953 design for his home on Taipei’s Jianguo South Road, in which the bedroom’s open roundel casually and naturally delivers us into a tranquil atmosphere, even though the whole residence follows an overall Miesian scheme, it smoothly integrates the language of Western contemporary space with the atmosphere of Chinese traditional space.

Through their struggles with the clash between East and West, Wang’s generation of architects found a unique spatial language in which their inner boundaries were revealed in every detail. Now, living in the so-called “global age,” that clash has become even more complex, and listening to the voice of nature (not necessarily limited to the world beyond the human realm, as humanity itself is an element of nature) has become incomparably difficult even as it has gained incomparable importance. Ultimately, the structure of real space is related to the paths of our own choosing.

Wang’s roundel disappeared along with the demolition of his building and remains to us only as an image. I hope this school, too, will not be limited to appearing only in my photo album or in my dreams.

Image credit: Left: photo Hu Fang; Right: spread from Ming-Song Shyu & Chun-Hsiung Wang, Rustic & Poetic – An Emerging Generation of Architecture in Postwar Taiwan (Muma Wenhua, Taipei, 2008).

August: This day

Pak Sheung Chuen

Pak Sheung ChuenIt seemed like the start of yet another ordinary day. What if this were the first day of man, or its last?

On August 23, those hostages sitting in that tour bus for almost an entire day with that frustrated policeman (1) – their day, in which they were victimized by the mistakes of others, a day of relations produced by systemic corruption (isn’t it amazing everyday is not like this?), is impossible to imagine. The approach of that moment when they announced their farewells…actually, just as I write these lines, in some corner of the world this kind of parting is taking place.

Because of the world’s ruthlessness, and its immense size, individuals have almost no means of resistance. What does it mean to be aware of “this day”?

What kind of hopes should we have for this day, or should we just give up?

This reminds me of the artist Pak Sheung Chuen’s plan for the Going Home Projects, implemented during the 2010 Taipei Biennial. Pak superimposed his own time upon that of others to create a day of mutual encounters and acquaintances with other people, almost eliciting potentiality from the impossible: as long as there are you, others and unexpected pleasures, this day can become an eternally beautiful memory.

Image credit: Pak Sheung Chuen – installation view of Going Home Projects (2010), Taipei Fine Arts Museum, 2010.

September: The silent cinema

Related to the movie of the empty theater; the movie of the projection that has gradually faded until you can only see darkness; the movie of your friends getting up from their seats and prompting other people out of theirs; the movie in which the only thing that appears are those two words, “The End”: it is only later that you suddenly see the movie of the vegetable market downstairs, the movie of the sidewalks, the movie of the home or the movie of your loved one right beside you.

Image credit: Both photo Hu Fang.

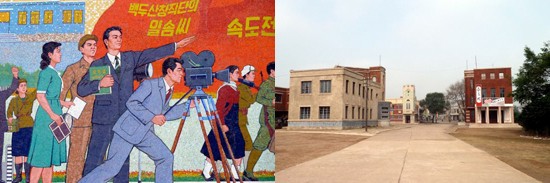

October: Film studio

On a visit to the Pyongyang Film Studios (the location site of the Korean Art Film Studios), you can feel the same energy as Shenzhen’s Window of the World theme park: the studio bears the captivation that people feel towards their own capabilities and the grand devotion they have towards re-sculpting reality.

The origins of the film studio and the production of feature films are related. Feature films always represent a certain perspective – and consciousness – based on a particular protagonist experiencing encounters in a particular environment, while the film studio filters out the chaos of reality and produces an environment that can better serve the films’ themes.

Perhaps fundamentally we live out different kinds of features; sometimes one plays the lead role, while at others one is thankful not to have top billing.

Some say that life in North Korea resembles a kind of performance, as though a certain unified power directs the people’s every action. From another perspective, others sentimentally say: here can be found the purity of spirit and the conviction that has already been lost in Chinese society.

Perhaps this contradiction can obtain its resolution in the film studio: accordingly, you can live the life you want to lead.

Image credit: Both photo Hu Fang.

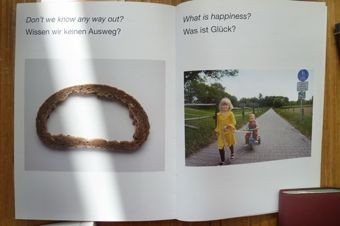

November: What is happiness?

Interview

InterviewHans-Peter Feldmann should be happy, since this year he was awarded the 8th Biennial Hugo Boss Prize.

There was fierce competition for the prize, with nominated artists aside from Feldmann including Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Cao Fei, Natascha Sadr Haghighian, Roman Ondák and Walid Raad. Considering Feldmann is approaching 70-years-old, if you say that the intense concentration and force of influence of his decades-long “inquisition” hardly requires validation from a prize, the award nevertheless gave everybody an opportunity to once again appreciate his works and thoughts, and became a joyous event to be shared by all.

Feldmann’s numerous projects often take form through printed matter. He transforms public images collected from daily life into a medium for examining the relations between humanity and the manifold events of the world. Through “montage”-style arrangements, these images are reformatted into a discourse on the spaces in which we live. In the book he made with Hans-Ulrich Obrist, Interview (Walther König, 2010), Feldmann used images to respond to all of Obrist’s questions, including “What is happiness?”

Image credit: Photo Hu Fang.

December: Every Day Except Christmas

After the last group of people leaves the shopping center, you’d think it would be possible to see the center in a “state of rest,” but already on the street outside a line of trucks – preparing to unload their cargo – are waiting for the workers who will direct their entry to finish their cigarettes and chatting. This lively atmosphere is enough to turn midnight into daybreak, when the center’s stomach will wait again for the stroke of midnight.

We usually assume that based on the order of time a city follows a kind of diurnal rhythm, hardly realizing that throughout all 24 hours of every day the city is home to activities that exceed our imagination.

Dziga Vertov’s Kino-Eye (1924) once drew our sight into the space of the city, presenting scenes from our daily lives and, behind those scenes, the ceaseless transformations of everything. Accordingly, Kino-Eye became a means for us to sculpt the myths of contemporary life. Looking at the films of the UK’s Free Cinema, from O Dreamland (1953) to Every Day Except Christmas (1957), one wonders what kind of scene – after several decades and viewed from across the expanse of time – our own conditions of contemporary life will present. Our clothes, gestures, diet, occupations, pastimes and pleasures allow us see how the machinery of society enters into and shapes the individual, day-in and day-out, and how individuals, revolving in response to a daily order abundant with rules, have worn down time.

In its observation of the world, Kino-Eye in fact unexpectedly attained a consciousness of super-human time.

Image credit: Left: photo Hu Fang; Right: still from Lindsay Anderson’s Every Day Except Christmas (1957), black-and-white, 37 min.

Things Worth Remembering 2010