III. Built to Ride

Monica Bonvicini on quotation as critique and the breakdown of language.

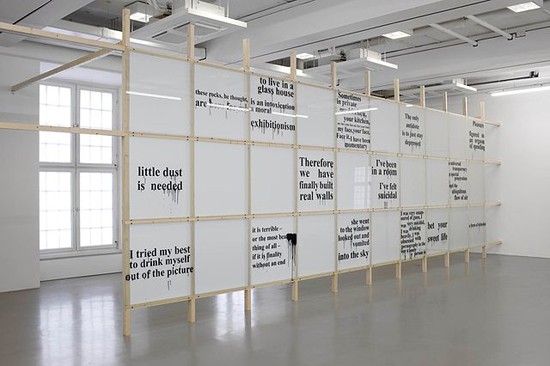

We Finally Built Walls (2010), wooden structure, 30 safety glass panels, black enamel color, 398 x 983 x 7.3 cm; photo Nils Klinger. All images: Courtesy Monica Bonvicini and Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin.

We Finally Built Walls (2010), wooden structure, 30 safety glass panels, black enamel color, 398 x 983 x 7.3 cm; photo Nils Klinger. All images: Courtesy Monica Bonvicini and Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin.ART iT: We were just talking about destruction, but another mechanism that frequently appears in your works is the use of quotations. For example, I Believe In the Skin… is literally a quotation of a statement by Le Corbusier, and you also make both formal and textual references to Modernism in other pieces. What does the mechanism of quotation mean for you?

MB: Over the course of making a work you throw many ideas into a crucible to produce one essential element, and in that process something stays or is even tattooed in your mind. I thought Le Corbusier’s statement, “I believe in the skin of things as in that of women,” was hilarious.

I like to read, I like to write, I like language, and sometimes language is more universal and easier to understand than the medium of sculpture. I have so many quotations that I write down here and there, and sometimes years later I like to put them together. It’s like your own little history.

Last year I made a work entitled We Finally Built Walls (2010), which compiles together quotations dealing with transparency, Modernism and architecture. I used glass panels from the ceiling of the Vienna Secession, which I had stored for almost 10 years, and painted quotations on them. I showed the work for the first time at the Fridericianum in Kassel. Secession was the first white cube in Europe, Fridericianum the first museum. When Rudi Fuchs curated the Documenta of 1982, he made the statement, “We finally built walls,” meaning that art – especially painting, because he was showing a lot of painting – needs real walls, since it’s real art. This way of talking about art is kind of funny and at the same time so transparent with regard to certain power games.

ART iT: There’s been a resurgence of artists revisiting Modernism and Modernist form. Some may have a stronger idea of what they’re doing and others may be less programmatic. Some may be responding to the aesthetic and others looking more at the context of the ideas. For you, is the quotation a form of critique?

MB: Well, I also love the Dadaists, and I’m coming a bit from that sensibility. I love the idea of Picabia listening loudly to the radio and keeping his studio door open because he wanted to be disturbed while working. I sympathize with that more than the painter sitting in complete seclusion.

It may be a little passé, but I want to be really precise about my works. Other artists might not want to describe or explain their works, claiming that it’s all experimentation. But I belong to a generation for whom, when we did the eight-hour critique class with Michael Asher, we couldn’t leave the room if we didn’t have a point and if it wasn’t discussed and slammed against the wall 15 times all over again.

Using quotations pins down exactly what you want to say, and establishes relationships to theories and philosophies that go beyond certain discourses. This is a form of critique that is to the point but not totally pornographic. I never put all my research on a table for everybody to see.

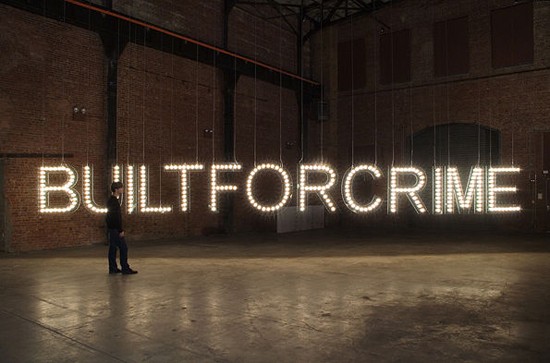

Top: DESIRE (2006), mirror polished stainless steel, aluminium structure, approx 230 x 1030 x 160 cm. Bottom: BUILT FOR CRIME (2006), broken safety glass, light bulbs, five dimmer packs, LanBox, airplane cables, approx 120 x 1235 cm, height from floor approx 150 cm.

Top: DESIRE (2006), mirror polished stainless steel, aluminium structure, approx 230 x 1030 x 160 cm. Bottom: BUILT FOR CRIME (2006), broken safety glass, light bulbs, five dimmer packs, LanBox, airplane cables, approx 120 x 1235 cm, height from floor approx 150 cm.ART iT: Do text pieces like DESIRE (2006) or BUILT FOR CRIME (2006) also have substantial research behind them?

MB: Desire is such an easy word, but, again, if you read about pornography or fetishism in relation to economy, then you see it in a certain way. I made DESIRE for a solo show in Los Angeles that took place in a shopping mall. I put the sculpture on top of the building, which was full of the logos of the various shops inside. I wanted to add something to this mess of words, names and graphics. Since I had made the letters so big, the piece was very visible and physical, but at the same time almost transparent, because on sunny days it would disappear into the sunny, blue Californian sky that was reflected in it. DESIRE is also a work about the fetishism of art, and who is desiring art. If you’re a collector, a museum director or an artist, it makes a difference in terms of what you need and want from art.

BUILT FOR CRIME I made for the Liverpool Biennial in 2006. It was sited close to the Tate and the International Slavery Museum. This was not necessarily why I chose the phrase, but I was conscious of that context. I did a later installation of the same work at the SculptureCenter in Queens in New York. From the yard outside the gallery you could see the Citibank building and the phrase took on new significance. “Built for crime” doesn’t even grammatically make sense, and with the sequenced lights the work is blinding and irritating to look at, so you have to wait before you can make out the complete phrase.

When I was living in Los Angeles I was fascinated by TV commercials for pick-up trucks: you see these trucks going through the Arizona desert pulling 10 cows, set to stirring music, half hidden in the dust they produce. To me this emphasis on toughness and protection reminded me of some commercials for the US Army, though they are much more clean. The phrase I used was inspired by a commercial by Ford saying something like, “Built to Ride.”

ART iT: Can you talk more about your interest in language? Is it the structure of language you’re interested in, or the poetry?

MB: Essentially I’m interested in language because it is the vehicle that makes complex communication possible, yet it also causes so many misunderstandings or even catastrophes – for example, the Berlin Wall came down because somebody said something the wrong way. Years ago I also read a lot about writing and reading disorders. I like these deviations, like how some people respond only visually to a printed page, but don’t fully comprehend the meaning of punctuation.

I love poetry as well, when it’s possible to say much with few words. I only speak three languages – all of them poorly – but I like all of them because they each have their own strange character and way of thinking.

ART iT: You mentioned Bruce Nauman. Is his use of language something you think about in relation to your own work?

MB: One of the best works is this cube you enter, and inside Nauman is screaming, “Get out of my mind, get out of this room!” (1968). How can you top that? It’s so perfect and beautiful. I’ve worked with sound, but not so much with the voice. I love Baldessari, and Mike Kelley’s drawings with the sentences. I love William Burroughs’ cut-up writings. I always love to read song lyrics. My final paper in high school was on the lyrics of Neil Young.

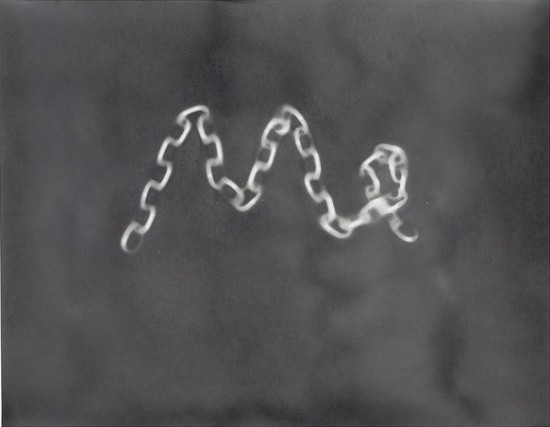

Me (2009), black spray paint on paper, framed 67.5 x 84 cm. Photo Thomas Bruns.

Me (2009), black spray paint on paper, framed 67.5 x 84 cm. Photo Thomas Bruns.ART iT: Lyrics can be quite nonsensical too, sometimes.

MB: Yes, if you don’t know the song. When I listen to songs in English, I often miss the lyrics, and then get disappointed when I look them up.

There’s a work I started years ago and never finished that relates to this. People think that when you’re really depressed, you would make dark drawings with black and red colors. On the contrary, if you’re so depressed that you need to be institutionalized, then you would paint white on white so that nobody can see anything. For this project, I used white ink on tracing paper to write down lyrics from love songs. At the time I was listening to classics by people like Billie Holiday, Nina Simone and Sarah Vaughan, and I would write down what I understood of the songs, which was an impossible task because I could never write fast enough to keep up, and I would also misunderstand the lyrics, especially since my English was not so good then.

I ended up with a collection of incomplete love songs. I’ve never shown these works, even though I was making them from 1995 until about five or six years ago. I only did songs that were really personal to me. I’m not sure why I stopped, but maybe as you age all these ideas about love and drama become less affecting.

This doesn’t mean I would never show the work. Sometimes you need some distance. Till now I’ve been very rigid, thinking that it’s bullshit to say that your life is your art. I was always totally against that. I never want to see anything that is overly personal. However, in recent years I’ve been rethinking my stance because I’m always working and have no personal life to speak of, and also because maybe there is some truth to the idea, and it’s just impossible for an artist to separate life and art.

Return to top

Monica Bonvicini: Erect As Sin