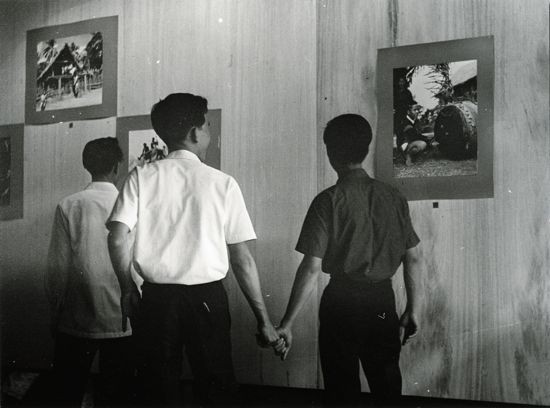

Cultural Boys, Saigon, 1962, from the installation “Good Life” at Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin, 2007. Courtesy Danh Vo and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin.

Cultural Boys, Saigon, 1962, from the installation “Good Life” at Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin, 2007. Courtesy Danh Vo and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin.(Cruising)

ART iT: Who do you stay with in Pacific Palisades?

DV: I stay with this American guy who spent many years working as an anthropologist in Vietnam, Joe Carrier. I come every year to visit him. He has been educating me in American history, his living experience. We have established a friendship.

ART iT: Joe Carrier is the figure who inspired several of your exhibitions using photographs of Vietnamese men from the war period. I wasn’t sure if he was real when I first read about the work.

DV: I don’t have the imagination to make something up like that, that’s why this has been a really interesting project for me to keep developing. It literally fell into my lap.

In 2006 I was in Los Angeles for a residency at Villa Aurora, which is located in Pacific Palisades. Residents there always give talks about their work, which the organization announces to the neighborhood. Joe lives nearby, so when he saw my name he came to check me out.

Had I come up with the idea to look for white men who had been to Vietnam during the war to cruise Vietnamese boys, it would have been impossible to find them because they’re disguised. As a matter of course it would be he who would approach me and not the reverse, because that was always the dynamic. I thought that was really interesting how the project’s beginning was following the “nature” of things.

ART iT: So you’ve never created fictional characters for your works?

DV: No. Which one should it be?

ART iT: I don’t know. The whole idea, the installation at Isabella Bortolozzi in Berlin with the crumpled business card and all of the artifacts – they add up to a history that is so real it becomes fictional.

DV: When Joe was cruising me at the residency, I was shocked because he’s already around 80-years-old and it was so clear that he was cruising me. Because Vietnamese phonetics has a soft “d,” my name is actually pronounced “Yan.” He pronounced my name correctly, and this made me curious – he is the first white person who has ever done that. I asked him how he knew the correct pronunciation and then he told me he had been in Vietnam from 1962 to 1973. Imagine, I was standing in front of this guy and could see he was cruising me, but at the same time he was talking about how he had essentially been in Vietnam during the whole war. Because he’s old he had to go home early, but he told me that if at any time during the residency I wanted to visit him I should drop by.

At 10am the next day I was there standing in front of Joe’s door. I was curious to learn more about him, and expected to end up with a kind of oral history. I visited him many times, and then one day he said that he wanted to go to Vietnam but is unable to travel alone and would need a companion. He was fishing for me to go with him, and I immediately agreed.

It was there in Vietnam, in Ho Chi Minh, when we saw men in the street still holding hands that he told me, “Danh, I’m as shocked today as the first time I saw it in 1962; I couldn’t help photographing it.” I asked, “Is this a joke, were you really there during the war taking paparazzi photos?” and he said yes. I asked whether he still had slides or negatives of the photos and he said that they were all there in his garage. He’s a magpie and has been living in the same house for 50 years, so what I’ve exhibited is only a fragment of what is actually there.

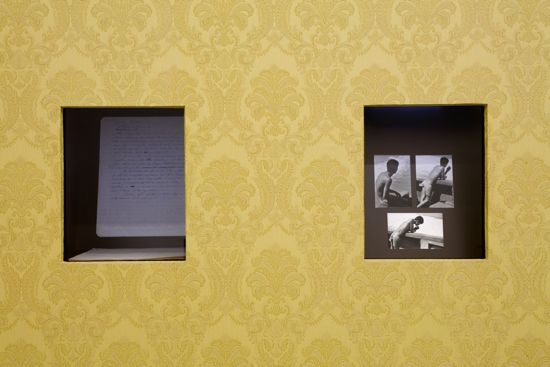

Both: Installation view of “Good Life” at Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin, 2007. Photo Nick Ash, courtesy Danh Vo and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin.

Both: Installation view of “Good Life” at Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin, 2007. Photo Nick Ash, courtesy Danh Vo and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin.ART iT: Would you say that across the different exhibitions you’ve deployed different interpretations of the material in a way that builds into one comprehensive work but also many different works at the same time?

DV: Yes, because as my relationship with Joe changes my perspective also changes. I don’t ever believe in the work as static. It’s important to return back to materials to understand them better. I don’t believe in art production as a statement. It’s a continuous research into the materials that you use.

ART iT: Is the relationship with Joe in any way different from working with your family? Perhaps there’s more of a surface relationship between child and parent because it’s harder to see around the edges, so to speak. When you learn about your parents it might come in flashes rather than the gradual process of getting to know a complete stranger.

DV: I’m not sure. I think that especially in my work with my father, I do get into him as a person. After using my father in many of my works, my perspective of him has changed. It’s also because the work is performative, in the sense that I have no idea where things will lead. It’s a way of understanding something better.

I never knew much about Vietnam and was never interested in the historical background. I guess in my parents’ case when they decided to leave everything behind they also mentally left things behind, and I was not raised with talking about the past. At a certain point, though, I grew interested in what happened and partly learned the history through my family. That was when I started to dig into it.

It’s my personality to sometimes cross other people’s boundaries. I did it once with my father and he asked me, “Danh, why do you want to dig up all this bad stuff?” The question still haunts me, and I wasn’t able to answer at the time. I still don’t have an answer. But I think that’s also good. It’s not because I’m seeking answers that I do this.

Danh Vo: A Five-Part Dossier on How Things Live