The Techne of Schadenfreude

By Andrew Maerkle

Since their first collaboration in 1979, Peter Fischli and David Weiss have consistently challenged the preconditions of art as a system of historically determined conventions. From utilizing materials like sausages and clay to carving exacting replicas of everyday objects from hobbyist’s polyurethane foam, they have reveled in inverting the oppositional values upon which art relies to produce its own uniqueness from the rest of the material world. Paradoxically, in collapsing art’s dialectical relationship with reality, they are able to show art for what it is: a discursive field that exists in a state of constantly reproducing itself. In doing so, the artists invite individual viewers to add their own opinions to that discourse, regardless of expertise or experience.

The pair recently visited Japan for the opening of their first solo exhibition at a Japanese institution, “Peter Fischli David Weiss,” organized by the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa. ART iT met with Fischli and Weiss in Kanazawa to discuss their practice in greater detail and how their works, often characterized by anachronistically labor-intensive production techniques, have changed with the rise of digital technology, as well as the possibility they raise of creating “transparent” art.

I. Gentlemen don’t work with their hands

Fischli and Weiss on the schadenfreude of copying in the age of mechanical reproduction.

Installation view of “Peter Fischli David Weiss” at 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, with clay sculptures from Suddenly this Overview (1981/2006) in foreground and C-print photographs from the series “Airports” (1987- ) in background. Photo Osamu Watanabe. All images: © Peter Fischli/David Weiss, courtesy the artists; Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zürich; Sprüth Magers Berlin/ London; Matthew Marks Gallery, New York.

Installation view of “Peter Fischli David Weiss” at 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, with clay sculptures from Suddenly this Overview (1981/2006) in foreground and C-print photographs from the series “Airports” (1987- ) in background. Photo Osamu Watanabe. All images: © Peter Fischli/David Weiss, courtesy the artists; Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zürich; Sprüth Magers Berlin/ London; Matthew Marks Gallery, New York.ART iT: Your works strike me as having an interesting relationship to both language and technology, in the sense that a recurring theme in your practice is the idea of mimesis, or the imitation of reality. You are often able to combine very abstract concepts with concrete results, as in the clay sculptures in Suddenly this Overview (1981/2006), which are incredibly manual but through their titles also seem to play with the gaps between language and representation in a way that anticipates the performative aspects of digital code. How self-consciously do you yourselves think about these issues when undertaking new projects?

DW: Certainly the clay figures are very narrative. We started with the concept that we wanted to make both important and unimportant events in the history of the world, but if you were to simply look at the figures without referencing the titles, you might not understand exactly what’s going on. If you see two people sleeping in bed, without the title it’s just two people sleeping. But then the title [Herr and Frau Einstein shortly after the conception of their son, the genius Albert] changes things and gives it another significance.

When we started we had all these small stories we were making but after five or six weeks we ended up with things like bread, because we had had enough of stories and wanted to make single objects where the title was exactly what the work depicted, without any metaphoric or symbolic meaning.

There are two other groups of works in which language plays a role, the photo series “Equilibres” (1984/85), for which we built structures and then interpreted them through the titles, and then the multimedia piece Untitled (Questions) (2003), which is of course a language-based piece.

PF: Also, when you work with someone else language is a very important tool. Talking is the beginning of every work we do. Maybe up to half the time we are in the studio is spent discussing ideas before we get around to making works.

In addition to the works David mentioned, “Sausage Photographs” (1979) includes one piece depicting a carpet shop [At the Carpet Shop] where almost none of the materials are altered – they are just sausages – and only through the title does the image become something else. Because “Sausage Photographs” was the first work that we made together, I think it is the beginning of this kind of strategy or interest.

And then the second work we made together was the movie The Least Resistance (1980-81), and there we were interested in the dialogues. So “Sausage Photographs” and dialogues plus talking in the studio, all these things are where it starts – the whole interest in language – and it’s clear that we are conscious about it or use it as a tool.

But we are also a little bit afraid, especially in the case of Suddenly this Overview, that it ends up being only about language. We don’t want to rely on it as an overall system.

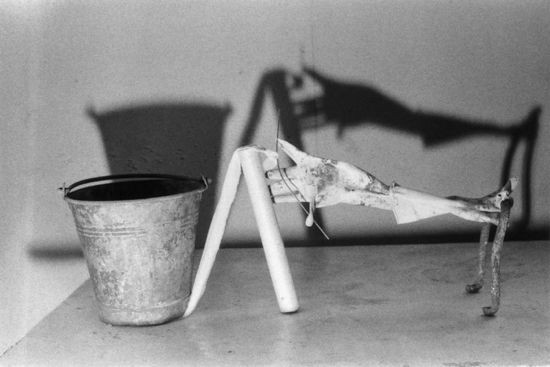

Above: From Suddenly this Overview (1981), “Herr and Frau Einstein shortly after the conception of their son, the genius Albert,” unfired clay. Below: Melancholy, Longing, Strategy (from “Equilibres”) (1984/85), photograph.

Above: From Suddenly this Overview (1981), “Herr and Frau Einstein shortly after the conception of their son, the genius Albert,” unfired clay. Below: Melancholy, Longing, Strategy (from “Equilibres”) (1984/85), photograph.ART iT: With the clay sculptures is there a difference in the relationship between idea and representation in creating an image of an anecdote as opposed to an image of an object, like a brick?

PF: With the brick we were interested in doing something that talks about the use of clay. In Suddenly this Overview there are actually two such sculptures. One is the brick and the other is the crib with baby Jesus, because everyone in Swiss elementary school has to make this scene in clay; it is the classic non-art clay sculpture.

ART iT: What happens when you use other materials? For example, what led you from clay to working with polyurethane foam?

DW: Basically it was a step towards making bigger things because clay is limited, it’s heavy, it shrinks, it cracks, so it’s technically difficult to use in making big things.

PF: And both clay and foam are cheap materials that you can easily buy. You can use the foam for constructions, it’s easy to handle. And it comes also out of the hobby market, people need it for making model airplanes or they use it in the film industry for set production, or they use it in restaurants for decorations. It’s the contrary of bronze and marble.

DW: Plus you can work very fast, and in the beginning that was very important.

Installation view of Untitled (2000/10) at 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, 2010. Carved and painted polyurethane objects. Photo Osamu Watanabe.

Installation view of Untitled (2000/10) at 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, 2010. Carved and painted polyurethane objects. Photo Osamu Watanabe.ART iT: Exactly. You often produce works in large groups. In its original version Suddenly this Overview comprised around 200 individual sculptures, while your installations of carved polyurethane objects painstakingly recreate the clutter of the everyday environment, down to the coffee stain on a used spoon. What drives you to make all this “stuff”?

DW: Depending on how precisely you paint it, it takes around three hours to make a rendering of a plastic bowl from polyurethane, and that consumption of time is a kind of schadenfreude: it’s the pleasure you derive from knowing you could simply go out and buy a plastic bowl for two or three francs if you wanted. It’s actually possible to use the fake bowl several times before it breaks, but there’s this aspect of taking an object out of use through imitation, like the sculptures of tools that you could never actually put to use. These works exist purely for the sake of representing a table or a chair or a packet of cigarettes, and in that sense they are illusions, in that what you see is in fact not there.

PF: Because we did not initially plan to collaborate for so many years together, we had to find a system for working together without getting on each other’s nerves, or at least not too much. I think we found a good model for working together from doing the clay figures for Suddenly this Overview.

We began by talking and then found a direction. From that moment on, we acted like single entities: David was doing his own sculptures and I was doing my own sculptures. Otherwise we would have started to argue about how to make a sculpture correctly, and then even if we only needed to make three clay figures to represent our idea, we would never have been able to agree on how to go about it.

By making many figures each on our own, we found the space to accommodate both our ideas. He comes up with ideas and I come up with ideas, and if he wants to do it his way then fine. I might not like it, but it’s ok.

Both: Detail of Untitled (2000/10) as installed at 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, 2010. Carved and painted polyurethane objects. Photo Osamu Watanabe.

Both: Detail of Untitled (2000/10) as installed at 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, 2010. Carved and painted polyurethane objects. Photo Osamu Watanabe.ART iT: David mentioned schadenfreude. The polyurethane objects remind me of a project Joseph Beuys did where he signed all kinds of common products, like a spade or a garden hoe. His idea of signing products in an attempt to short-circuit the capitalist economy seems to be driven by a similar kind of romantic perversity.

PF: I think there is actually a big difference between our carved objects and Beuys’ signing. The signing is more like this touching effect. We often use the expression “as if” to discuss our works. It is “as if” a carved object is an ashtray, “as if” it is a tire or whatever, but the objects themselves are not there. A chair is made for sitting, but you cannot sit on our chairs; they would immediately break.

So what does that mean? It means only the aspect of looking at the chair remains for the viewer, and the object is removed from its slavery to be used as a chair. People always reference the idea of the Readymade here, but our works are in a way the complete opposite of the Readymade – we have to make them, we have to make them ready!

DW: Plus the selection of what we can carve and what we want to carve is quite limited to the things we know. We had the idea of replicating objects lying around in the studio but we did not want to fake complicated things. We felt uncomfortable with things in cases where we didn’t understand how they function. A radio is already on the edge of something that we could reproduce: I don’t really know how it functions inside.

PF: So instead of a radio we preferred to carve tape cassettes. Almost everybody of a certain age has had the experience of having to open a cassette and rewind the tape.

You could also talk about the carved objects in terms of classical still lifes, where you make a composition with objects and these objects tell a story. If we wanted to create the situation where viewers see these tools and food and think that there may be workers using the installation room, and maybe these workers listen to music while they are working, then we would include a cassette piece in the installation to establish this idea that the music is there.

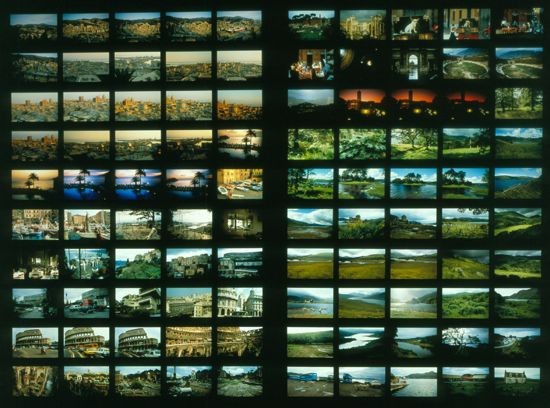

Detail of Visible World (1986-2001), set of 15 light tables with 3000 photographic slides, 83 x 2805 x 69 cm.

Detail of Visible World (1986-2001), set of 15 light tables with 3000 photographic slides, 83 x 2805 x 69 cm.ART iT: What you say about “as if” and the nature of objects brings me to your later photographic series like “Airports” (1987- ) and Visible World (1986-2001) that deal with large volumes of images. The rise of the Internet and its concurrent proliferation of digital photography has produced a crisis for the identity of images, where we are now all asking, what makes an image unique or significant? What is your relation to the images that you use in these works?

PF: I had a discussion recently with a photographer in Zürich. He said to me that his profession is in a way obsolete now because all the images we can possibly have already exist, and you just grab what you want from a databank. It no longer makes any sense to go to Zermatt and take your own photo of the Matterhorn.

Even when we made Visible World we had already reached a point where all these images had already been made, but I think the fact that we did something that makes absolutely no sense is now the important part of the work. We decided that even if the images have already been made, we would go to these locations and make our own images, and we did.

It’s almost like the more useless the action of taking photographs becomes, the more the work increases in significance. You can’t get away from personal experience.

DW: When you go to the Pyramids and you’re standing there, you already know them exactly, because you’ve already seen them from most of the angles possible.

When we started Visible World we were already on the edge of this phenomenon, because there were already image banks that released these catalogs of their holdings, which we collected and even made into artist books.

PF: We made books out of the catalogs and already had an interest in these image banks, but then if you look at our own photographs you will see they are a little bit off. The image bank photos are super professional and idealized, they go to a point that we maybe didn’t really go to. So when you compare our photos of the Matterhorn with the image bank Matterhorn, the differences are in some way similar to those between our carved objects and the real objects: they are not 100 percent there.

At the Carpet Shop (from “Sausage Photographs”) (1979), color photograph, 24 x 36 cm.

At the Carpet Shop (from “Sausage Photographs”) (1979), color photograph, 24 x 36 cm.ART iT: You have said previously that projects such as Suddenly this Overview and “Sausage Photographs” were inspired by a desire to work with materials that would ordinarily not be approved in the art context –

PF: Yes. Especially in the early 1980s making art with something like clay was even more of a complete taboo – it was arts and crafts – although today since artists are going back to ceramics it becomes part of the language. I think it was the writer Walter Grasskamp who first used the term “disgusting techniques” to describe this phenomenon of artists working with taboo material – Rosemarie Trockel and her knitting, for example – and this search for different materials.

ART iT: – then is Visible World your “disgusting technique” work for the digital age? At a time when artists are pushing themselves to make the most unique images possible or to in some way resist the proliferation of images, it seems like embracing the ubiquity or banality of images could be considered an artistic taboo.

DW: No, no – we didn’t know what was coming. We tried to take pictures that were completely impersonal, that were very common and belong to the collective knowledge of famous places and landscapes, so that way people could recognize them immediately.

PF: When we showed the work previously, we always had people asking us where we went to make all these photographs and so on. Now, people ask us, “Where did you find all these images, which databank?” It’s the first time that this issue has come up.

DW: “How long did you have to spend on the Internet until you found these images?” We could do it for sure, but it would be a completely different work.

Part II. Roman Holiday

Fischli and Weiss address the transparency of the visible world.