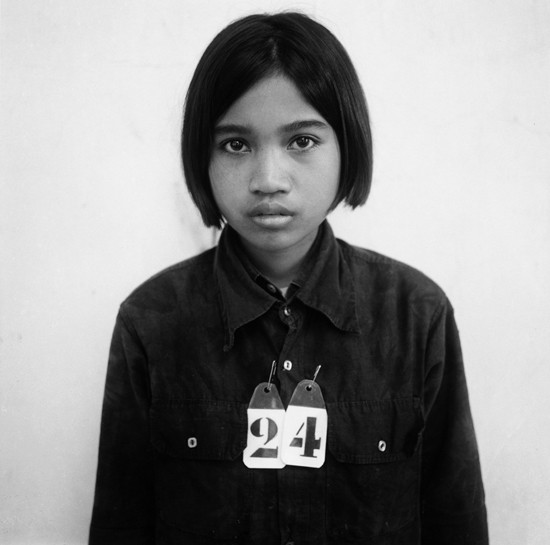

Unidentified Prisoner, Tuol Sleng Prison, Phnom Penh, Cambodia (c. 1975-79), photograph. ⓒ The Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocide, Cambodia/Doug Niven

(New York) As Asia gears up for its periodic convergence of large-scale international art festivals in cities across the region this September, the 2010 Gwangju Biennale got a jump on the competition when this year’s artistic director, Massimiliano Gioni, unveiled his preliminary artist list at a press conference at the New Museum in New York on April 20.

Gioni, who is also a curator at the New Museum, has chosen as his theme “10,000 Lives,” referencing an eponymous 30-volume epic poem by the Korean author Ko Un. Ko was active in the 1970s and ’80s Korean democracy movement and jailed four times over that two-decade period. He came up with the idea for his epic poem, which comprises lyrical portraits of every living and historical person that has influenced him, when jailed in 1980 following the Gwangju Uprising in which citizens clashed against forces representing the country’s then military dictatorship.

Noting that this year is the 30th anniversary of the uprising, an event that was the inspiration for the Biennale’s founding in 1995, Gioni told ART iT that he sought to connect current trends in contemporary art with the local history of Gwangju. “The title of Ko Un’s book serves as a metaphor and inspiration for an exhibition that looks at both the lives of people as told by the images they leave behind and the lives of images themselves,” he said. “We live in a world so over-populated by images that images have taken on life of their own, to the point that it is time to ask ourselves, what do images want?”

Like its namesake, Gioni’s exhibition will be sprawling in scope. The more than 100 artists and artist groups confirmed for participation represent a time span from 1901 to the present and an eclectic selection of both era-defining art stars, relative unknowns and art world outsiders. Unconventional juxtapositions include Gustav Metzger, who originated the concept of Auto-Destructive Art, with Jeff Koons, whose saccharine pop sculptures have come to epitomize the excesses of the recent contemporary art market boom. The flamboyant James Lee Byars, who once staged his own death in a gold-covered tomb, will share space with the irreverent Maurizio Cattelan, known, among other works, for a lifelike mise-en-scène of the Pope crushed by a fallen meteor. Other notable names include Fischli & Weiss, Roni Horn, Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy, Bruce Nauman, Tino Sehgal, Cindy Sherman, Sturtevant and Andy Warhol.

Yet, such established artists are potentially a mere sideline to another current in the show that looks beyond the contemporary art canon. Also included will be Canadian collector Ydessa Hendeles’ Teddy Bear Project (2001-03) archive of images of people with teddy bears, as well as black-and-white mug shot photographs of prisoners at Cambodia’s Tuol Sleng Prison taken before their executions by the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime in the late 1970s. A masterwork of Chinese Socialist Realism, the life-size sculptural tableau Rent Collection Courtyard will be making its international debut at Gwangju. Made by students and faculty at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute in 1965-78, the work depicts peasants resisting a tyrannical landlord, and was famously recreated by Cai Guo-Qiang for the 1999 Venice Biennale, earning the artist a Golden Lion. Also of note, original prints by the commercial photographer Hanyong Kim will be displayed stripped of their advertising copy, providing an uncanny window into the sensibilities and aspirations of late 20th-century Korean society.

The selection of artists from Japan also breaks with convention, avoiding names common to the biennale circuit. The selection includes the post-war multimedia group Jikken Kobo, active from 1951-57 and rarely if ever seen in international exhibitions, as well as the mixed-media artists Tetsumi Kudo and Shinro Ohtake, who emerged in the 1960s and 1980s, respectively.

Gioni explained to ART iT that he was looking for artworks that could expand the theme in unexpected directions. “The theme can guide the research, but then the art has to take over or complicate the theme, reveal its complexity and richness,” he said. “Art should never be reduced to a simple illustration of a theory.”

Gioni went on to compare “10,000 Lives” to a complex visual atlas or taxonomy. Then he reconsidered the analogy. “Actually I think the best way to describe it is probably as a sort of gigantic family album – one that cannot avoid being dysfunctional, of course.”