RESTRUCTURED HISTORIES

By Akira Rachi

Bell Peppers (2012), C-print, painted frame, 29.2 x 36.8 x 3.8 cm. All images: Unless otherwise noted, courtesy Elad Lassry and Rat Hole Gallery, Tokyo.

Interview:

ART iT: You are best known for your photographs, but actually have a diverse practice that spans films, sculptural objects and performance. Seeing your exhibition here at Rat Hole Gallery, what struck me is that in your works the frame acts like a container into which any kind of image can be placed. Can you explain more about the relationship between image and frame in your work, as well as how you select the images that you use?

EL: I began the process of questioning the relationship between image and frame in school. I would create image archives, collecting images from different sources and genres – images made for commercial purposes, like headshots and publicity shots; images from instructional books and text books; images from manuals and so on. Then, in considering all of these images, I would start by locating the aspects that I found to be problematic or questionable. Sometimes, when I found a particularly haunted image, I would use it as I had found it. But when an image didn’t exactly fit my questions, and instead revoked the questions I wanted to emphasize, I would respond by making a picture of my own.

What I noticed is that I was responding with my own archive, making my own pictures in response to archives that had entered into circulation and been affirmed or recognized by other institutions or authorities. And the frame became a way to articulate this condition of making new pictures that are the ghosts of hundreds of other pictures. I wanted my pictures to have the quality of the readymade or something that already exists in the world. There had to be a duality to them: they are singular and exist in the frame, but at the same time, the frame is also a host for a picture that can change.

ART iT: What led you to start using this kind of frame?

EL: I was not interested in photography so much as I was in pictures. It was a troubling position for me, because I was surrounding myself with pictures, but my rationale for this diverged from what Modernist notions of photography find to be curious about pictures. As such, in displaying my pictures, I was tempted to respond with something that would evoke a shelf, although I didn’t want to resort to such an easy solution.

At the same time, I found the color frames to be problematic. They were almost embarrassing, and still are. They are potentially ugly or overdone, too chunky, too suggestive of mass production or of toys, but I was interested in using that to challenge the photo. I wanted to make the photo carry the frame and still find an existence. The frame became a sculpture and an object, as well as a trap and obstacle for myself.

The first time I made the pictures I thought of the frame as a way to negate them from the status of photography. As opposed to it unequivocally being the subject, the C-print would become a façade for the box; the frame would claim a presence equal to that of the image. In the work there is a resetting of ideas: why is this a frame and this a photo?

Left: Collie (Brown) (2012), foil on offset prints on paper, painted frames, painted metal poles, ceramic beads, ribbons; three framed works, each 27.3 x 19.7 x 3.8 cm; installation 53.3 x 95.9 x 35.6 cm. Right: Bouquet (2012), charcoal drawing, walnut frame, 36.8 x 29.2 x 3.8 cm. Bottom: Installation view, Rat Hole Gallery, Tokyo, 2012.

ART iT: I understand the problematic aspects of using colored frames, but in making the works you also use specially colored backdrops. I get the feeling that something is compressed in that color which responds to the subject of the photograph.

EL: The seamless background is interesting because it has such a multiple history. On the one hand, it now has connotations of consumerism, commercial photography, advertising and so on. On the other, it recalls early experiments in photography and portraiture. So in the work there is a back-and-forth between several economies and institutions, and the different ways photography is used in the world.

Also, through the histories that are addressed in the work, I’m exploring what kind of engagement is possible with pictures now and what kind of experiences we can have with them. You have the eye and the brain. The eye sees the object in front of it, while the brain interprets that image based on a set of knowledge: the human eye only needs a few dots for the brain to recognize a face. And this leads to the question of how much of what we see has been compromised or adjusted by our minds. The connection between the mind and eye offers a really curious space for resetting.

ART iT: I think this also affects the exhibition space. Actually, when I entered the gallery and surveyed the space, I was confused as to where I should focus first.

EL: That’s good to hear. In the show I included recent works in which I have started challenging the medium by skipping photography altogether. My previous works attempted to dismantle the built-in quality that comes with the picture and now I am questioning whether this dismantling can be applied to something like a charcoal drawing, which comes with a different set of histories and problems. Collie (Brown), for example, also plays with the idea of using analog means to reflect the cyber-like, imaginary space the photo occupies.

I think what I try to do in the work is to talk about contemporary concerns, but claim them through analog methods. This points to the problem with a picture that cannot be explained by one condition – it cannot be because of digitization or because of authorship. It points to the philosophical questions around photography and how from its inception the picture has offered a haunted space.

Moving between these multiple problems allows the viewer to reset, re-experience and revisit the action of looking without escaping into knowable, already processed problems. It’s almost like a set of obstacles that the viewer has to navigate. The designated space that is marked by a ribbon net extending from the wall in Collie (Brown) was a way for me to playfully suggest the 3D-like property that a picture can take, and of course in this case it happens to be that of a collie dog – the cinematic dog, Lassie – which comes with its own history of being in TV shows and movies. I’m trying to open up this portrait and ask, within the legacy of Lassie and within the decorative space that I create for these images, could it still be considered a portrait of a dog?

Both: Installation view, David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, 2012. Courtesy Elad Lassry and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

ART iT: Even in your still images, especially the double-exposed images and diptychs, there are some moving elements, which remind me of Muybridge’s motion studies. Were you interested in the relationship between still and moving images from the start?

EL: Yes, absolutely. I was interested in exploring them and working with them at the same time. I think of the pictures becoming films and the films becoming pictures. Obviously, film is a series of pictures, and when you consider the space in between each frame, you also have to account for an afterimage. This is the space in film where the mind compensates, and I think this effect also happens when you look at a series of photos. You shift between two photos to create a third photo. Sometimes a photo of a man and a photo of a dog can become a photo of a man and a dog and vice versa.

ART iT: This structure is also apparent in films like Zebra and Woman (2007).

EL: Yes. Even the films raise questions on the history of portraiture sitting and an awareness of the apparatus, like when the cameras used to have long exposures and people really had to sit still for their portraits to be taken. So the portraits always vacillate between the idea of the headshot – ubiquitous, meaningless commercial pictures – and these potential portraits. There is always the possibility that it does capture something, yet at the same time, it’s never clear to what extent that possibility exists. There’s a suggestion of, say, a resurrection of the picture, the picture reclaiming a space that we don’t know; but it’s an exploration, not a strategy.

ART iT: The movement of the camera in your films is also compelling in the way that it makes viewers aware of the existence of the frame.

EL: It comes from an awareness of Structuralist film and the moment of working with film outside of the cinematic structure, whereby the viewer doesn’t have a predetermined condition for how to watch the film. Viewers can walk around and choose their own experiences. Also, because the films are on a loop, viewers can enter and exit at will and choose the beginning and end. The film is really treated as a picture, and of course it’s a projection, but in a way I’m also treating the pictures as projections, in that they echo multiple histories and shift within their frames. That’s the kind of movement that happens. Even when it’s just one image, they almost channel more than they can handle. Maybe they’ve been through too much.

ART iT: In your exhibition at David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles in 2012, you incorporated a wave-like obstruction running across the exhibition space that alternately obscured and revealed the line of photographs on the wall behind it. This also seems to emphasize the connection between serial photography and moving images.

EL: Yes. I was interested in the idea that the installation could become a motion picture. With the performance I do now, I’m looking at what part of the apparatus can be eliminated while trying to create an experience that feels mediated – as if it’s been through a lens-based apparatus – even though it hasn’t. Similarly, with the exhibition at David Kordansky Gallery, if you walked through it, you would become conscious of how the conditions of mediation look and could then hopefully retrieve them.

Both: Untitled (Ghost) (2011), 35mm color film, silent, 18 min. Courtesy Elad Lassry and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles.

ART iT: Returning to the topic of film, you use dance in films like Untitled (Ghost) (2011). Can you explain your interest in choreography?

EL: My interest in choreography has to do with the human subject as a form, with dance being this occasion where a troupe – a collective – essentially make a picture with their bodies and, in doing so, abandon themselves as individual subjects.

In all of the films with dancers, there is a back-and-forth between the dancer reclaiming herself as a subject and a break to sequences of portraits. A lot of the tension with dance happens for me in this duality. On the one hand, the body serves the making of a picture, while on the other it is a human subject and its representation has both a force and history that distracts from the picture.

There’s also a cultural aspect that comes with it, which is a very challenging thing to dismantle. It’s a challenge to take dance and ask it to be considered as a purely formal image that’s divorced from its connotations, whether it’s the history of ballet or the socio-economical context and so on. So there is an attempt in these pieces to aggravate these histories, extract that picture and recondition it.

ART iT: But it seems that more than simply being conscious of history, you also try to challenge and expand it.

EL: Yes. I think history is an education, but in terms of the possibilities of experience, it’s also a trap, so there is ambivalence in terms of my relationship to history. I believe in histories that are multiple and not linear. They are there and they are relevant, but I think of them with a sense of rhythm that can shift around: restructured histories.

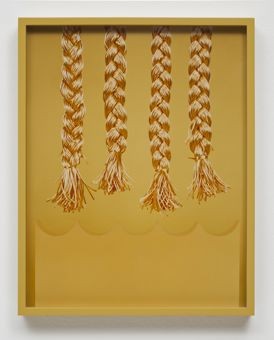

Left: Four Braids (Yellow) (2012), C-print, painted frame, 36.8 x 29.2 x 3.8 cm. Right: Plinth (Blue Liquid) (2012), silver gelatin print on C-print, painted frame, 36.8 x 29.2 x 3.8 cm. Bottom: Untitled (LF Green Bed) (2012), beech wood, paint, 71.1 x 91.4 x 51.8 cm.

ART iT: Previously you have said that you want to avoid doing simple appropriation.

EL: What I meant is that, when I use appropriation, I’m not overwhelmed by the act of appropriating. The focus is not so much on authorship. I’m more interested in the presence of the image itself and what it means once it’s in the space. I think the act of appropriation can overwhelm some works, preventing them from being considered in terms of what happens after appropriation.

ART iT: It’s similar to the way you reactivate specific images or pictures from those already in circulation.

EL: Exactly – by making them singular again. Many times, a picture that has been in circulation will become a unique piece through the addition of a stamped foil or a silkscreen. The picture reclaims itself as singular, even though it’s an image that’s been circulating.

ART iT: Given this process of returning images to singularity from circulation, how do the different images in your archive relate to each other?

EL: In my case, there is the option that the photographs don’t relate to each other at all. If they do, it’s probably through a thread of vocabularies and art historical canons that have already been established – for example, typologies – the sense that there is a “type” photograph. There are several threads that suggest the potential for a standard, the potential for something that has been accepted and has some kind of collective agreement upon it. But it’s a dormant faculty that creates this impossible typology. I think the connection is mostly cultural and relies on a series of accepted visual ideas within culture.

Elad Lassry: Restructured Histories