The Legacy of Objects

By Andrew Maerkle

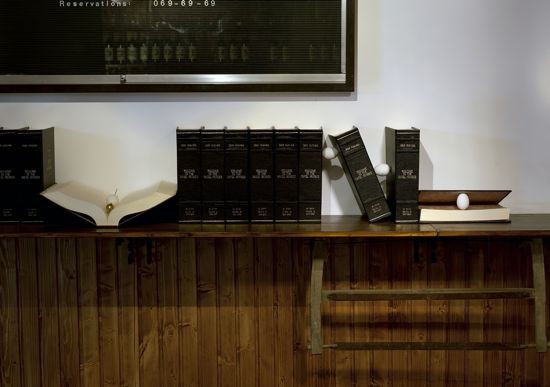

Installation view of Welcome to the Hotel Munber (2010) at the 3rd Singapore Biennale, 2011, mixed media, dimensions variable. All images: Unless otherwise noted, courtesy Neue Alte Brücke, Frankfurt, and TARO NASU, Tokyo.

Interview:

ART iT: Many of your works subtly combine mechanisms of both eroticism and archaeology in an investigation of how objects talk. The installation and performance you have in the Singapore Biennale, Welcome to the Hotel Munber (2008- ), goes even further in its premise that the central figure of the work is an amateur erotic writer. To begin with, could you discuss your approach to erotics?

SF: Erotic art is rarely taken seriously. I thought it would be comical to try making erotic art that goes into deep psychological and social issues the way that the works of the Surrealists or Bataille did in the past.

My use of eroticism is also in a sense about dealing with gay identity, and the lack of choices that gay men have to talk about their sexuality. For example, I wanted to understand whether it’s possible to fuse the discourse of gay identity with the idea of family, in contrast to the prevailing theme of gay erotica that tends to celebrate the creation of a new, all-male family in exclusion to preexisting familial relationships. And of course the idea of reproduction is central to the performance: What is the legacy of a homosexual child? If he’s not going to have children, can he still carry the family forward?

On the other hand, my work is not really about eroticism at all. Eroticism is a foil for holding the attention of the audience and keeping people interested in the rest of the material. If I have eroticism as an overriding lead-in, I’m free to talk about anything, such as a specific moment in Spanish history that has been largely forgotten by the broader international public – almost nobody has a personal relationship to it any more. So it’s a way to help the audience get into that material.

Finally, there’s also the idea of conflict, which is very much drawn from Bataille: the idea that eroticism is something that will always be in conflict. Bataille talks about it in terms of a primitive man’s gesture of creation, which will never be resolved with civilized society. This idea of conflict drives the whole story.

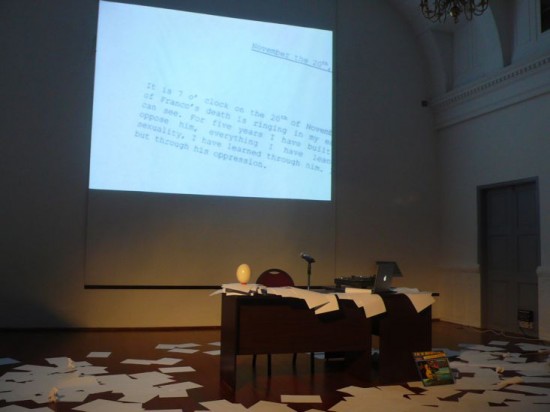

Top: Detail of Welcome to the Hotel Munber (2010) as installed at the 3rd Singapore Biennale, 2011. Bottom: Installation view and detail of Desk Job (2009) in the Nordic Pavilion of the 53rd Venice Biennale, 2009, mixed media, dimensions variable. Photo Anders Suneberg,

ART iT: Is Bataille’s Story of the Eye one of the texts that you draw from? One could find parallels, for example, between the use of the ostrich egg as a prop in your performance and the connection between eyes, eggs and sexuality in Bataille’s story.

SF: Yes, Story of the Eye is one of the texts by Bataille that has influenced me, as well as some of his more academic essays. It’s difficult to determine what erotic writing should be, because the quality’s not always there. That’s why with this performance I chose to start with the subtext that it was written for these cheesy gay magazines, in order to keep the pitch on a low level from the beginning. That way the audience doesn’t have any expectations of high literature, or even erotic literature for that matter.

ART iT: Setting aside the idea of erotic content, do you approach the installation component of the work through a consideration of the erotics of space? In the way that you conceive of the erotic narrative content as a “lead-in” to other material, do you think about the relations between objects as a mechanism for getting people to engage with the work?

SF: Absolutely. This was a major concern with my installation for the Nordic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2009, Desk Job, which I developed at the same time as the performance for Hotel Munber and is in some ways an offshoot of the performance, dealing again with the figure of the erotic writer who writes about his life. Because I couldn’t be there in Venice to perform for the entire six months of the exhibition, I had to find a way to translate into a sculptural situation the sense that the audience of Hotel Munber experiences of constantly trying to piece together what is true and what not, and trying to piece together the story and understand what it really is. All the material is unverifiable – the whole lot – so you’re really left to your own devices, which emerges from a classical theatrical idea of allowing the audience to ultimately decide what actually happened.

With things like Desk Job and the installation component of Hotel Munber – which is a different part of the same work – my question was, how can people get something out of looking at the installation? It’s enough for me that they can go in and say, “OK, Franco, Spain in the 1970s – I know something about that.” If you don’t have those basic references, that then there’s no beginning, so you have to have a certain level of knowledge. But if you have those references, then you can sort of understand that it’s about my parents, you see my father in the bar with the young child, and then there’s a few things that are obviously erotic, or pornographic, really. What was interesting after the first time I showed it was that people started to think that everything in the installation was erotic – the castanets, the baskets, the dripping candles – and they started to understand that they are implicit in the reception of the work because it’s all coming from within their own heads. I’ve just given them a few tasters, and the rest is in their imagination.

I like to put the emphasis back on the audience’s own psychology, because of course with work like this you could easily tell someone the story, you could guide them through it by the hand, but that wouldn’t leave them space to add their own experiences to the interpretation or reconsider their own families or what their own histories are in relation to their parents’ histories. So the responses varied widely from interest in approaches to reconstructing history to identifying with this idea in the performance that one can maintain a relationship even with an estranged parent. The responses varied widely from the personal to the political.

ART iT: The work also seems to sensitively touch upon the sexual tensions that occur between parent and child, both in terms of how the child affects the parent’s sexuality as well as how the parent models the child’s sexuality.

SF: Yes. It’s interesting that despite how homoerotic it is, few people define it as a gay work. They completely understand it as a work about sexuality in general, and that this is just one instance of the battle between homosexuals and Franco, which could equally unfold in a heterosexual context or in any other kind of social institution.

ART iT: Do you have any concerns that it could be labeled as a gay work?

SF: I’d like the work to be as universally appreciated as possible. I hope people could enter it without thinking that it’s part of a closed society. The main character, my father, is a straight guy who’s been turned into a gay guy, so you could choose to identify with him, or you could identify with my mother, who’s silently in the background of the whole thing, and imagine what it’s like for her to have a son who’s talking about this situation. There are a number of options.

In the process of making a work like this with so many different references, it was important to play the shock factor of those readings against the more analytical, literal descriptions that come afterwards. I certainly think it’s important to be vocal about homosexuality, especially in places like Singapore and other parts of the world where it’s not as freely spoken, and which are not that different to Franco’s Spain in that sense.

There’s a definite political undertone, but it’s always worked out through fiction and a shared metaphorical space rather than an unequivocal documentary-type situation.

Top: Installation view of Phallusies (An Arabian Mystery) (2010) at Manifesta 8, Murcia, 2010, mixed media, dimensions variable. Bottom: Installation view of Frozen (2010), commissioned by the Frieze Art Fair Cartier Award, 2010, mixed media, dimensions variable. Photo David Grandorge.

ART iT: In tandem with the erotic elements in your works are the archaeological situations you create, whereby the discrete components seem to communicate a broader narrative, but simultaneously retain the right to refuse communication – they are, after all, just objects. What led you to begin working in that way?

SF: Having studied architecture before entering art school, I never believed in the essentialized image of the artist – an image that still persists in many ways. When I was making sculptures in art school, I was always more excited about talking about them and the connections between them and things that weren’t visible, and trying to convince people that there is a connection, and finding that space between object and the spoken work or text I was quoting. I always enjoy seeing that shift that occurs in a person’s mind when they imagine a certain book that was written in 1850 and then look at a broken egg and make a connection between the two. I thought this could be a beautiful, potent form for me to use.

Also, I’d been trained in architecture school to talk about my ideas through constantly having to do presentations of models and sketches and having to convince juries that I could make this building that’s going to change the world and be sustainable and bring people together and tick all the boxes of “zero carbon emissions,” and so on. Yet actually what you’re talking about is a lump of cardboard. I found it philosophically comical that so much work happens in rhetoric and dialogue and that objects themselves don’t really matter, and of course this extends to advertising as well: no matter the product, they all receive this massive storytelling treatment.

There’s a kind of lack of respect on the one hand for objects in themselves, but on the other hand through the texts one can understand the power of objects or sculptures. So my sculptural installations are almost like theatre sets, and I work similarly to a film or production designer who is constantly asking, “Does the Coca-Cola in the frame tell a story or not?” That’s exactly how I think. I think about it in psychological terms that are almost didactic, because all the components are telling a story, and because that story is so complex, if I didn’t give those immediate signals the audience wouldn’t be able to get further with it.

ART iT: But in art coding and exclusion can also be productive. Not everything has to communicate equally to everybody, in contrast to the advertising or architecture approach.

SF: Certainly. There are always things I add to the installations or performances that are tangential or make no sense, or there’s wasted imagery, such as a few slides that come up during the Hotel Munber performance that briefly take the audience somewhere else or make an association with something that I said before or will say later but is not explained. I like throwing in a wild card here and there.

Also, the emotional element has been a point of discussion in particular with this performance. I’m aware it’s a very brain stimulating performance. If you like to read or like literature and fantasy, then you’ll like this performance because you get this very clear fiction-analysis-fiction-analysis, poetic-analytic structure the whole way through. Then at the end when things break down and I start to become emotional, you aren’t sure how deeply affected I am, and whether I’m now becoming my father, and whether my father’s crying because he realizes he’s becoming Franco. This is a moment that you can’t define in any emotional category. You’re left with this shocking end that is unplaceable and upsets the things that have gone before.

It was important not to preach to the audience. People were really angry that I added this cheesy, emotional thing at the end, but that’s exactly why I did it, because it needed something that could throw viewers into doubt as well, such that everybody has to respond differently and in their own personal way. That’s why I describe myself as a closet expressionist. Expression is a bit of a dirty word, just as eroticism has been a dirty word. Why is that? Why have we lost that? Perhaps it’s because we tend to want to preserve and institutionalize everything – and where do you put emotion in a museum?

View of stage for the performance version of Welcome to the Hotel Munber at the Singapore Biennale, 2011. Photo ART iT.

ART iT: As an artist do you feel tension, then, between making performances and installations? Do you feel an emotional tension between acting something out versus leaving it in a space?

SF: I use tension as a technical device, pairing things that will spark off other things. With a performance, the tension between analysis and fiction is simply a device to ensure that it’s dynamic and that it doesn’t become one long talk. The fiction is necessary because it puts people in a metaphorical state. It takes it away from me, such that suddenly we all access a shared sphere where we’re all imagining the narrative and none of us are physically part of it, and it keeps the narrative from looking like a kind of therapeutic self-analysis session. When you’re dealing with autobiographical material, or supposedly autobiographical material, or the form of autobiography, then of course you’re always skirting these traps of being pinned down into certain positions, but I use it to break open identity and enable associations to form the audience response. People always want to psychologize an artwork and add their own emotional rationale to it, and that’s the power that I’m harnessing. I’m trying to slip between the tag on the wall explaining where I was born and what the work is in order to find that subconscious place where you can manipulate the audience to think what you want to tell them.

A special solo presentation of work by Simon Fujiwara is on view Feb 25-26 in the stand of Taro Nasu at G-Tokyo 2012. He is also the subject of a solo exhibition at Tate St Ives, on view through May 7.

Simon Fujiwara: The Legacy of Objects