II.

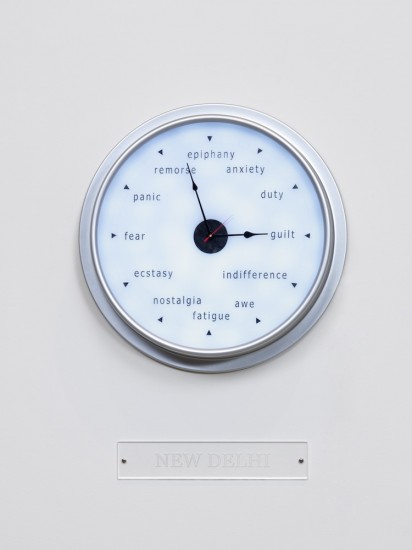

Escapement (2009), installation with 24 Clocks, three reverse clocks, four video screens, sound track. All images: Courtesy Raqs Media Collective.

Escapement (2009), installation with 24 Clocks, three reverse clocks, four video screens, sound track. All images: Courtesy Raqs Media Collective.ART iT: We were just talking about planetary consciousness and how people and ideas circulate around the world. Art today is more global than ever, but because of disparities in public funding, infrastructure and market volume, couldn’t we say that a large part of the discourse of contemporaneity still runs through the US and Europe, even if it is more dispersed or multi-centered than before?

SS: It is a mistake to assume that contemporaneity is a trans-Atlantic, Northern Europe and American Eastern Seaboard phenomenon. That is an illusion produced by the peculiar conditions of the 20th century. Previous historical epochs also had this illusion. Intellectuals, writers and artists in 12th- or 13th-century Baghdad and Basra must have thought they were at the center of the world then. Because of the social and cultural capital that rested on a certain kind of mercantile capital of the time, they fell prey to the illusion that people in northwestern Europe did not count as embodiments of global culture – because they simply were not. Certainly the Chinese civilization thought of itself as being central to everything – they called themselves the Middle Kingdom. So this is just another temporary phenomenon.

If we take the longer view, then we have the opportunity now to say that the reason why this time is different from all previous times is that it dissolves the claim to imperial superiority from any particular point of the globe. It would be a mistake to assume that this will be the so-called Asian century. That would be a recapitulation of the European era. This is a planetary century. From now on, we have to think in terms that are different from those that have been produced by local cultures and nation states.

Contemporary art is at the cusp of this problem because contemporary art speaks a sensory language that acts as if it does not need translation. In literature, people have to do the hard work of translating the text word by word from one language to another and publishing it as a book. With contemporary art, as long as the shipping works, you just move the artwork from one place to another, change the language of the wall label and write an essay about it. It’s assumed that the cultural glue is transparent. But actually, even where it appears as if it does not need mediation, art requires just as much translation as literature. When a European curator perceives a work of contemporary art from Africa or India, it appears to be just an object or image like any other. It does not seem to require anything else to be able to process it. So curators make two mistakes. One, they think that the object speaks a derivative language, a language invented in Europe. The second mistake is to think that the object can be understood, and if it cannot be understood, then the problem is not with oneself, the problem is with the object. Why does this happen? Because to this point the education of the curator and the critic and the museum director has not required people to enter into the idea that they might not actually know what they’re talking about. In most other disciplines, there is a tacit acceptance that one may not know the object of inquiry. But in art, because of the limitations of the discipline of art history, there is an assumption that one knows provenance, one knows style, one knows different markers so as to be able to create an immediate taxonomy of the object. In fact, something that looks exotic is easier to understand within this taxonomy than something that looks familiar. That’s where the enigma of contemporaneity lies, and the problem arises.

ART iT: Raqs Media Collective started off working in documentary film. What drew you to contemporary art?

SS: It was the hospitality of that moment when a progressive, utopian potential of the planetary seemed possible. The work we were doing did not have many takers in the world of film and video then, but we began persistently getting invitations from contemporary art exhibitions. The first two were in fact documenta and the Walker Art Center. And people assume documenta came first, but chronologically the invitation from the Walker came earlier, it just took a different time to unfold. In or around the year 2000 there were many different initiatives being produced all over the world, and especially in Asia. This was when Tokyo Wonder Site was established, for instance, and we were producing Sarai in New Delhi as a physical space, a discursive platform and a research program. It was also when the potential of the Internet as a means of communication among cultural actors was just being discovered. So there were a series of fortuitous as well as inevitable consequences that turned the attention of contemporary art toward people like us, as if we were pioneers, which we were not. We were just doing what was necessary for us to exist. I think a lot was read into us as harbingers of the future, but we were actually trying to consolidate our present, not lay claim to the future.

Escapement (2009), detail.

Escapement (2009), detail.ART iT: Does being in contemporary art also mean being in history, or working in history? Is that implicit in the name “contemporary art”?

SS: Yes. It would not be less implicit if we were in literature or philosophy, but I think we can make a claim to saying that contemporary art is also an invitation to revisit the possibility of a dialogue between different artistic practices. The individual artist and the specific art form are but one moment in the history of art. Before the 18th century, the individual artist did not exist in the way we recognize today, and neither did the specific art form. Art happened at the intersection of practices. I think we are returning or rather moving forward to a similar possibility at another stage, and to be there is to be in history at all times. If we are expressing the consciousness of our time in anticipation of the future, we are in history, no matter what we are doing.

ART iT: You often reference the relationship between Rabindranath Tagore and Okakura Tenshin. Their correspondence is a reminder that notions of contemporaneity were already in play a century ago. Another example is the Futurist Manifesto, which was published in a partial Japanese translation in the May 1909 edition of the literary magazine Subaru, just months after it appeared on the front page of Le Figaro. The translator, the novelist Ogai Mori, had a column compiling one-line news items from around the world called “Mukudori tsushin,” which could be loosely translated as the “Starling Bulletin,” but in contemporary terms suggests the idea of “Tweets from Abroad.” On the other hand, today translation can easily get bogged down in issues of copyright and licensing. The famous example here is Nicolas Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics, which still lacks a proper Japanese edition.

SS: I was delighted when I visited the Tokyo University of the Arts Toride Campus the other day. I had asked the students to bring in different sources of inquiry or problems and questions they had. There was a young Chinese student who showed a slide of a copy of a book of texts by Raqs in Chinese – but the pirated edition. So clearly things move quicker than we imagine them to be moving, and one reason for this is that people access them using networks that are not necessarily respectful of the barriers of intellectual property. Now, the student posed the question, “Why should I even read this?” which for me was even more interesting, because it was based I think on the underlying assumption that, if something is so easily available, then why even bother? There is actually something beautiful about a young Chinese artist at a Japanese art school downloading a pirated Chinese edition of the translated works of the Raqs Media Collective and asking why she should even read it. This means we have come a long way from expressions of curiosity about the other. This young artist takes that reality for granted. This is her environment, so she neither treats it as special nor as exotic. It’s banal. And the sheer banality of our presence in her consciousness is for me the greatest sign that we have moved forward.

So we celebrate the difficult relationship between Okakura and Tagore – it ended badly –because it represented a superhuman effort on the part of two individuals, towering colossi of their time, to actually connect with each other. But let us also recognize that this desire for connection is no longer a desire. It is now the reality. So when one very humid summer day in Calcutta, Okakura wrote, “Asia is one,” he knew Asia is not one. He was expressing a desire. But I don’t even have to say, “Asia is one.” We don’t even have to think of Asia and the world in numerical terms anymore – whether it is one or many. We just live the reality.

This applies to the Futurist Manifesto as well. Marinetti wrote it in the aftermath of a car accident in which he was so shocked by the velocity of the accident that he realized speed and time had irrevocably changed. He was able to access the future because of his accident: he was able to access another way of thinking about time. But the accident happened because the car was traveling at the remarkable speed of 25 miles per hour, which, in 1919, was unimaginably fast. So today when we think about how time is compressed because of the high speed at which we operate in the world, we should remember that we live our lives in the kind of slow motion that can only happen when you speed up the cranking rate of the camera. Now there is a peculiar reversal of ideas of distance and speed. What seems far away is near, what seems near is actually quite far, and all these reversals contribute to the dizziness of the contemporary moment.

Revolutionary Forces (The Three Tasters) (2010), rotating platforms, custom built surfaces, apparel, script, two DVDs, two DVD players, monitors, actors.

Revolutionary Forces (The Three Tasters) (2010), rotating platforms, custom built surfaces, apparel, script, two DVDs, two DVD players, monitors, actors.ART iT: What is your response to this dizziness? Are you trying to lay down anchoring points, or are you surfing it?

SS: The term we chose for our name, raqs, assumes a vortex, a rotation, a revolutionary form of being in movement and kinesis. We chose it because we also wanted to mark the idea that this kinesis or velocity was also in its own way a contemplative move, paradoxical as it may sound. People tend to think of contemplation as something that emerges from a slowing down or a stillness of the senses, whereas we are saying that the world we are living in today actually requires us – if we wish to be contemplative – to be in movement. For instance, anyone who has played the children’s game of twirling around would know that the moment of dizziness happens not when you are in motion but rather when you stop and the world continues to rotate because your senses are still processing it in that way. We are trying to find that moment of clarity. Well, maybe “clarity” is not the right word – my colleagues don’t like it, though I do. Let’s call it instead a moment of being “in sync” with the demands of a different rhythm, of an acceleration that has its own equilibrium: an equilibrium that is achieved through the torque of rotation.

ART iT: You’ve made a number of works about love, a theme that stands out from among the other topics you’ve addressed in your practice, but which is certainly relevant to thinking about desire and contemporaneity or, indeed, being “in sync.” Where did this particular strain of works come from?

SS: Oh, it’s because we’re getting older and sentimental in our middle age. But I think that one pays more attention to desire and its presence in the world and in life when there is a sense that there is a lack of it in the world – when there is an active absence of love in the world. I think love is a revolutionary engine.

Shuddhabrata Sengupta: Within Me Latitude Widens