The Scene is Elsewhere: Tracking Ming Wong

By Adele Tan

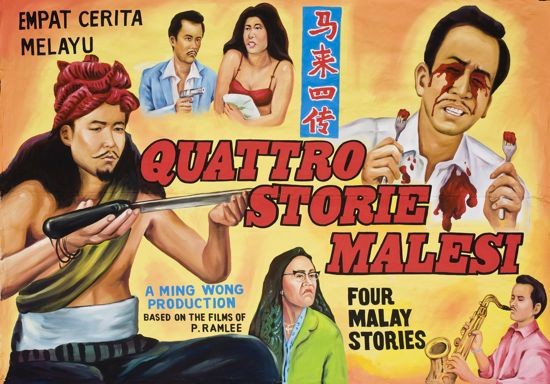

Cinema billboard designed by Ming Wong, painted by Neo Chon Teck (2009), variable dimensions, acrylic emulsion on canvas.

Cinema billboard designed by Ming Wong, painted by Neo Chon Teck (2009), variable dimensions, acrylic emulsion on canvas.All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages.– From William Shakespeare’s As You Like It, Act II, Scene VII

The above lines from William Shakespeare are an apt entry point for a discussion of Singaporean artist Ming Wong’s body of filmic work, which circulates around the vicissitudes of role-playing. In truth, in Wong’s work there is not so much a stage as there is a set, with the action that unfolds in the artist’s videos at times appearing to be maneuvers of set pieces. What this expresses is a kind of ecstatic obsession with rehearsed positionalities obtained through existing iconic films, a passion already observable in Wong’s early prints in which he etched surreptitious but melodramatic glimpses of life backstage. Yet Shakespeare’s lines also imply the passage of time, the inexorability of history and the transience of being. This sense of time does not merely relate to the nation or culture – a burden of representation that Wong seems to bear rather well – but also the evolution of an artistic life, the life of art and its artists. The deep space of art practice and the innumerable surface possibilities available cannot preclude that agonizing temporal decision of “what comes next?”

Wong’s career as an artist has been far from conventional. Once a shy science student from an elite junior college in Singapore, Wong spurned the well-worn path to a university degree for a fine art diploma from the Nanyang Art Academy. He did eventually earn a graduate degree but that was to be an MFA from the Slade School of Art in London. Straying and staying away has forged Wong’s own practice and his reception as an artist. In this sense it is ironic that when Wong was awarded a Special Mention at the 53rd Venice Biennale in 2009, in a particular category called “Expanding Worlds,” the jury commended him for “examining the history of Singapore’s multiethnic cultural identities via the demise of the country’s once flourishing film industry…and [using] innovative forms and techniques to reflect on the sense of shame and exclusion that accompanies the imposition of racial and sexual stereotypes.” Having spent many years in London and now a long-term resident of Berlin, Wong does not come first to mind as a likely “reclaimer” of Singapore’s heritage (although history is best recuperated from a distance). Yet the interpretive parameters set by the award and the national pavilion, as well as the international honor bestowed by the prize itself, conspire towards Wong becoming “reclaimed” by his nation-state. Wong thereby comes under the threat of being captured by the stereotyping gesture that he had striven to put under critical and ludic pressure. This is no parable of the prodigal son, but rather the story of an artist who could only be welcomed back into the flock once he had achieved a certain professional standing overseas, tellingly so when he was included in the exhibition “At Home Abroad” at the Singapore Art Museum in January 2009, around the time when his candidature for the Venice Biennale was decided.

It was also entirely commensurate that it was the arch post-colonial theorist Homi K Bhabha (as a Venice Biennale jury member) who articulated the reasons for awarding Wong a Special Mention. He had, perhaps all too predictably, found Wong’s work to be “both very clever in artistic terms and also very socially perceptive.” The theoretician – and his theory – find affinity with the art that has been spoken of as speaking to his theory. Bhabha’s book The Location of Culture has been indispensable in providing conceptual heft to the currency of mimicry, stereotypes, difference and identity within contemporary art strategies. Wong’s practice certainly takes off from this prepared ground, but in reading him solely through that context might we be prematurely surrendering him to neat, taxonomic categories? Can we dispense with the social frame and look at the “veneers of language and identity” not in terms of nation-building and cinematic history but as the very substance of art making and the making of the artist-self?

All: Installation view of “Life of Imitation” in the Singapore Pavilion at the 53rd Venice Biennale, 2009.

All: Installation view of “Life of Imitation” in the Singapore Pavilion at the 53rd Venice Biennale, 2009.There is of course Wong’s undeniable attempt to bring into focus what Singapore had lost and could have become through the use of film and cinema. Wong’s careful documentation of lost and abandoned cinemas is itself a political enterprise, exalting the cultural potential and heady multi-ethnic mix of the film industry’s glory days in the 1950s and ’60s, but at the same time excoriating the aesthetic and intellectual paucity of the present. On the face of it, Wong and the curator Tang Fu Kuen, who oversaw the Singapore Pavilion, have presented the audience with a mesmerizing trip down memory lane – which has now toured from Venice to the Singapore Art Museum (April 2010) – in the form of a movie theater replete with its characteristic vestiges: the installation includes large canvases advertising the exhibition created by the last surviving billboard painter in Singapore, a full-scale archival display of movie memorabilia from a dedicated but eccentric Singaporean collector of such ephemera, vintage cinema seats and a cinema-shaped peep box in which one can view footage of abandoned cinemas. A nod to a once-thriving Malay movie industry in Singapore too is provided by Wong’s Four Malay Stories, a four-channel black-and-white digital video installation that recreates key scenes from four iconic movies by the Malaysian director P Ramlee – Ibu Mertuaku (1962), Labu dan Labi (1962), Doktor Rushdi (1970) and Semerah Padi (1956) – with Wong as the only actor playing the combined 16 characters (1). While we are probably induced to proclaim the multi-talented entertainer as representing Singapore’s heritage, more difficult to embrace is his assimilation of the tragic, violent or insalubrious content of the films’ storylines. Like the character Kassim in Ibu Mertuaku who, in a fit of Oedipus-like rage, chooses to blind himself with a fork after learning the truth of the plot of love deception woven around him, this cultural and historical visage spun by Wong and Tang may not be palatably or safely consumed.

A survey of Wong’s more recent offerings, however, does suggest that he is shifting gears from cultural interrogation to introspection. No longer immersed in a national cinema, Wong’s fascination with the medium sees him exploiting film as a vehicle to carry forth an inquisition of his own self, first as the emblematic cultural outsider and then as a mid-career artist who is searching for the next breakthrough in his practice. Wong’s love of cinema seems less mortgaged to his country but rather more in service of his own needs. His well-worn tropes and devices become the means by which he locates not culture but himself in an indeterminate or inchoate matrix of time and space. All of his characters and their speeches require dispersal and condensation in one way or another: the lines from P Ramlee are repeated, translated and juxtaposed; the Caucasian actress playing both Maggie Cheung’s and Tony Leung’s characters from the Wong Kar-Wai film In the Mood for Love struggles with the script’s Cantonese diction, as displayed in various degrees of improvement across Wong’s three-screen installation In Love for the Mood; and in Life of Imitation the black mother and her daughter who passes as white in Douglas Sirk’s film Imitation of Life are reinterpreted by three male actors of different ethnicities who cross-dress for the two female parts and who seamlessly swap roles throughout the video. Two facing projections of this remake are then doubled by their reflections in mirrors placed beside the projections. But for whom does Wong intend these dispersals, reversals and misrecognitions?

Installation view of Life & Death in Venice / Leben und Tod in Venedig / Vita e Morte a Venezia (2010) at Galerie Invaliden1, Berlin.

Installation view of Life & Death in Venice / Leben und Tod in Venedig / Vita e Morte a Venezia (2010) at Galerie Invaliden1, Berlin.These diegetic breakdowns have been summarily accounted for as being motivated by Wong’s outsider status, his racial otherness in Berlin and the dispossession of his cultural memory in Singapore. Yet Wong’s maneuvers have also increasingly looked towards art and aesthetics. In Life & Death in Venice, Wong takes apart Luchino Visconti’s film (and Thomas Mann’s novella) by playing both the aging protagonist G Aschenbach and the beautiful youth Tadzio, imitating Aschenbach’s twitches and funny walk and Tadzio’s insouciance as depicted in the film. Wong used the opportunity presented by his exhibition at the Venice Biennale to shoot at the original locations of the Visconti film, such as the Grand Hotel des Bains and the Lido Beach, and incorporated various art pieces at the biennale into his mise en scène. Wong’s presentation of his work on two suspended facing screens (a third screen shows Wong sight-reading Gustav Mahler’s Adagietto, the soundtrack of Visconti’s movie) in which the Aschenbach and Tadzio characters both stroll the city independent of each other emphasizes the seeking, furtive gaze of Aschenbach. His eyes supposedly track the portentous beauty that lies ahead but which was also time past. He is thus also a symbol of decay and futility, becoming the very thing that he had loathed: the old fop in the background who exaggerated his countenance to appear youthful. The only way however for desire to be kept alive is through the separation of Aschenbach and Tadzio, so that they will never be self-identical. The only certainty present within Wong’s work is the act of Aschenbach’s and Tadzio’s walking, and it is left unclear whether they are walking away from or towards each other.

Installation view of Devo partire. Domani / I must go. Tomorrow (2010) at PAN Palazzo delle Arti Napoli.

Installation view of Devo partire. Domani / I must go. Tomorrow (2010) at PAN Palazzo delle Arti Napoli.Perhaps this is why Devo Partire. Domani / I must go. Tomorrow came soon after Life and Death in Venice. Announced as the “Next Change” at Wong’s Singapore Art Museum exhibition, there is no mistaking what Devo Partire. Domani potentially comments on. A remake in Naples of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema (1968), in which a stranger suddenly appears in the lives of a bourgeois Italian family and proceeds to subvert its foundations by engaging in sexual relations with all the family members and then mysteriously disappearing, this work once again features Wong playing all the characters himself, both the transformer and the transformed. To be perpetually departing means that one is always already entering another time and place, which is what the characters all eventually do, spurred by the unforeseeable violence of daily passions and trauma, and captured by the decrepitude of Neapolitan industry and the long shadow of Vesuvius. For someone like Wong who has lived peripatetically, he of all people must know that the price of art is that measure of inauthenticity, a life of imitation that stands as a bulwark against identity. Only then can the artist refuse the status of cliché and defer that endgame of artistic death. Therefore, we might possibly never need ask: “Just who is Ming Wong?”

Ming Wong‘s solo exhibition “Life of Imitation” is currently on view at the Singapore Art Museum through August 22. Wong is participating in the upcoming 8th Gwangju Biennale, “10,000 Lives,” at multiple venues in Gwangju from September 3 to November 7, and his solo exhibition, “Gruppenbild,” opens at the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein on September 28, continuing through November 5.

Adele Tan completed her PhD in art history at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London and is currently a curatorial fellow at the National Art Gallery, Singapore. She was previously assistant editor at the British journal Third Text.

All images courtesy the artist.