THE LORD OF CREATION AND DESTRUCTION

By Andrew Maerkle

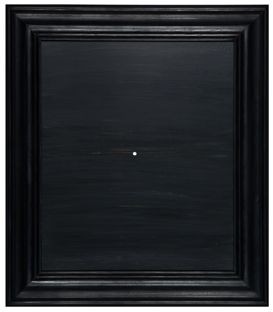

Both: Oh Shiva (The Lord of Creation and Destruction) (2009), double-sided acrylic on board in artist’s frame mounted on pedestal, 147.3 x 40 x 28 cm (37 x 32 x 4 cm and 110 x 40 x 28 cm). All images: Unless otherwise noted © Djordje Ozbolt, courtesy Herald St, London, and Taro Nasu, Tokyo.

ART iT: Your works reference an eclectic range of historical styles, from Old Masters to Indian miniature painting and Orientalist painting. Is there anything programmatic about the way you approach these references?

DO: Not consciously. My works generally reference loads of things but I think it all happens more on a subconscious level. I don’t really have any preconceived ideas about the paintings, even when the end result might give that impression. Sometimes I develop the ideas while I’m working, but usually I just put everything into the painting.

In that way my painting simply reflects my interests. I do follow what’s happening in contemporary painting, but I’m looking more closely at older stuff, combined with things that emerge from my living and working situation and whatever catches my attention in passing in the street.

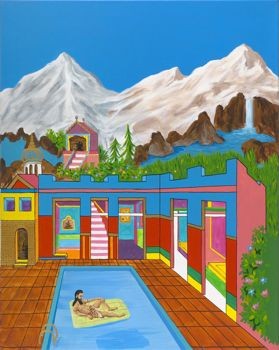

Also, I have almost an obsession with India. I go there all the time and live there and bought some land there. I literally like all things Indian. India pops out in many of my paintings. There’s no “Indian period” or whatever, but I am surprised to see how symbols and references emerge in so many of my works. From the beginning it has been a constant in my work, and somehow it takes precedence over other interests. In 2009 I had a show at Herald St Gallery in London with several rows of double-sided paintings installed standing on plinths. All the plinths were the same height except one that was taller than the rest, and in the end on the tall plinth I put a painting depicting the iconography surrounding depictions of Shiva, Oh Shiva (The Lord of Creation and Destruction) (2009). The show wasn’t about India or anything but that work was there and somehow elevated over all the others. For example there’s another painting, At Home (2006), with this colorful depiction of a guy with a beard relaxing in a swimming pool. That’s also inspired by India. The buildings in the background come from a postcard with a temple and some Indian gods that I reworked into a house structure. It’s a kind of wishful thinking. I would like to be that guy in the Himalayas living like that. I think it all comes from my Indian obsession.

ART iT: So you’re drawing from sources like existing paintings as well as things like postcards?

DO: Not necessarily referencing, but I find inspiration from all the things I look at. I guess in that sense there are stories or false narratives in the paintings. It’s not my intention to tell a story but somehow the story is there.

I usually don’t talk about the work. That was my early rule. I wasn’t interested in explaining anything. I’m still not keen to do that, because I don’t think it’s relevant. You can talk and talk. Maybe it’s nice to explain a few points to people that might help them to understand the context better, but in a way I think it’s all there, and there’s nothing that could be made better by explaining everything.

I’m quite prolific and I try not to think too much about my work. I intentionally try not to think. I just make things. It’s almost mechanical or subconscious work. I found that whenever I used to sit down and look at my works in progress, I’d start thinking too much and it wasn’t adding anything. It was just taking away because there are always questions, and it’s pointless because inevitably you get to the existentialist questions like, Why paint in the 21st century?

I did years and years of art education where you just talk and talk, endlessly discussing things. I don’t mind having passed through that process – it was quite nice – but at some point you realize it doesn’t help. That’s my personal opinion. I’m sure there are people who just love to talk about anything. But for me it’s pointless. Like anything else – living even – once you start questioning things, you get to the fundamental why.

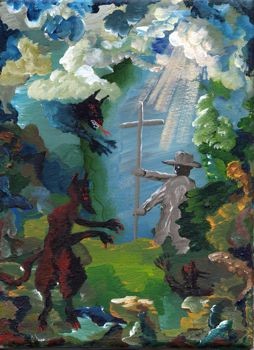

Left: At Home (2006), acrylic on canvas, 100 x 80 cm. Right: The Defender (2004), acrylic on canvas, 24 x 18 cm.

ART iT: Then, why do you paint in the 21st century?

DO: I enjoy painting. It’s the most banal answer, but I really do like painting. I’ve tried other mediums, but this one I really like. I don’t think it’s a cliché when people say they started drawing when they were kids. You have that affinity from an early age, and in my case I just followed that feeling. I never considered that in this age painting is not the way to do it and that I have to go out and buy a digital camera and a computer or whatever.

I think the most important thing with painting for me is literally the physical process of making the painting. That’s the most exciting part for me, and once one work is finished I immediately move on to the next. It’s like I’m trying to paint an eternal painting that never ends. I’m addicted to painting. I’m always looking forward to the next painting, not the previous ones. It’s like a constant movement. And with the installation of my exhibitions I always do it quickly as well.

ART iT: Do you think at all about where you fit in a contemporary landscape of painting or a historical tradition of painting?

DO: I don’t know. I’ve thought about it from time to time, but I think it’s pointless. Is it important? How does that work? The whole hierarchy in arts or any kind of order is for me pointless. The history is important in terms of seeing what happened when, but otherwise nothing is black and white. It’s always a subjective view. Once you get into the art world and see how it all happens and the machinery and the business side – then you begin to see all these elements that can be puzzling for an artist as a student or a young man with romantic ideas about what art can be. So I don’t really think about that.

ART iT: Where did the obsession with India start?

DO: It started when I was really young, I was a bit of a hippy. Many of the friends of my older brother used to go to India: just hop on a bus and then five days later they would be in Afghanistan and then on to India. I think everyone has something which, even though he can’t really explain why, has some kind of connection to him and stays with him. It literally never changed for me from the first time I encountered the idea of India. I was a young man and I just wanted to leave home and go and live in India, without really even knowing where to go or what I would do. It was this kind of mythical place. The longest I stayed at one stretch was a year-and-a-half. I liked everything, the culture and religion, going trekking and walking the mountains, and I was also painting there.

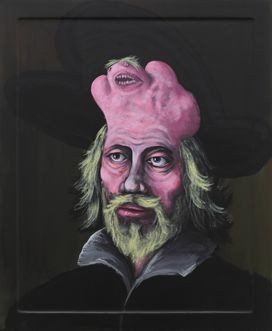

Left: Just the Two of Us (2009), acrylic on icon board, 60 x 49.5 cm. Right: Madonna di Tutti Frutti (2009), acrylic on icon board, 59.8 x 49.4 cm.

ART iT: But does the icon board format that you use also come from India, or is it from Orthodox Christianity?

DO: The icon board is from Orthodox Christianity, which is the tradition I was raised with in Serbia. We were not religious, but that’s the religion that is dominant in Serbia and Russia and Greece. I don’t think anybody has ever used the icon boards for anything else because they are exclusively made for religious paintings, which are usually portraits of saints or depictions of episodes like Saint George killing the dragon. So I thought that by using them I would be somehow lowering this religious custom while at the same time elevating contemporary subject matter to a religious level – you could look at it either way.

I quite like the object in itself. It’s quite chunky. They’ve been making it the same way since the Middle Ages, from the same wood. I first thought of using it because I was back home on a visit to Serbia and wasn’t happy with the readymade canvas they had there. When I saw the icon board I thought that it’s much nicer as a surface and an object, and now I paint almost exclusively on wood panel.

I still use the icon boards sometimes. I recently did a series of saints. The obvious one was Andy Warhol. I put him in the kind of landscape they would use to depict the saints. Then I did Trotsky, with the ice-pick sticking out of his head. They used to depict saints in their martyrdom, with their heads cut off or something, so I was just playing with that on the icon board as I was painting. I wasn’t trying to be clever but that’s just what happened. There’s no hierarchy, it’s just a painting.

ART iT: Why did you start making works to be installed on plinths?

DO: The plinths were also a chance thing. I usually find it difficult to take a day off work because I think it’s a waste of time with the brushes, but occasionally I do. I used to share a studio with Matthew Darbyshire, and we would just hop on a motorbike and go out see shows together, whatever was on, and one day I stumbled upon a painting by Dürer at the National Gallery, which was a double-sided work that was installed on a plinth. I saw it and immediately thought I have to make paintings like this.

So the idea came and then I was trying to work on what I’m going to paint on each side of the work so that each would have a connection. Sometimes it was almost like a call and response relationship and sometimes it was more obscure. Once it was all done what I really liked was walking through the gallery and seeing them all for one side and then turning around and seeing a completely different exhibition.

Installation view, Herald St, London, 2009.

ART iT: How was it responding to yourself?

DO: It was a different experience. I didn’t know what to think and then as I said earlier I decided not to think. The show itself received a weird response. People didn’t know how to look at the works: there was the whole issue of putting a painting on a plinth and the doublesided-ness that people couldn’t seem to work out. In hindsight I find it was probably more interesting than any other show I’ve done. But it was nothing new. It’s not like I invented fire, and I even clearly stated that I was inspired not only by Dürer himself but also by the presentation of his piece that happened to be done by the National Gallery installers.

ART iT: Aside from using the icon board, have you ever referenced Serbia or your background there in your works?

DO: Not really, because it never inspired me. I did in a negative way. I made a painting of a tree with 20 people hanging its branches, and called the work something like “Spring Cleaning,” referencing the ethnic cleansing that took place during the wars in Yugoslavia. But I was always interested more in eclectic things and traveled a lot even as a kid, so there was no hierarchy for me between different cultures. I don’t think Serbia influenced me so much as general popular culture at that time, and we got more or less everything. It was all there, so there was no distinction between American music and Russian films in that sense.

Another intentional thing was not to be too political. At one point I really disliked this fashion of political artists or artists dealing with strong social issues or trying to comment on things from gender to whatever – you think, Please, not another one. Certainly there are artists dealing with that in a way that I find really appealing and interesting, but there are so many who are dealing with it in a limiting way. Certainly identity obviously reflects in anybody’s work, but to me it’s mostly irrelevant. Now I no longer feel passionately for or against anything. I just observe things that I think could be interesting, even if they don’t always come out as interesting as I would hope.

ART iT: You mentioned education. First you studied architecture and then did close to 10 years of art education. Was there a drastic change in your approach to art between the beginning and now?

DO: In a way, yes. You go through the process whereby for various reasons you try different things because you’re influenced by someone, or you’re insecure as a student and you want to come up with something clever instead of just painting flowers. There are many students who out of pure insecurity stick to something they think is clever or cool, or cooler or cleverer than something else. You need experience and maturity to free yourself. But, that said, there are many older artists whose work was much better when they were younger, and again in that case maybe you find people sticking to one thing because of insecurity.

You learn through the context of art school that maybe you don’t need an art school. But there were interesting points, and of course you get a studio in the middle of London – the Royal Academy was brilliant – and there were nice teachers to talk with, and simply through talking with them – not necessarily because of anything specific they say, but rather through the whole process of talking – you get something sorted out.

Both: Oh Shiva (The Lord of Creation and Destruction) (2009).

ART iT: In that sense rather than mapping out ideas in your studio and then coming up with something that works and then producing it for the public, there’s no real barrier between what you’re doing in the studio and what the public sees?

DO: Yes. Out of however many hundreds of paintings I’ve made over the years, there are maybe no more than five that I have destroyed or never shown. I think everything should come out. I like these oddities that even I’m not sure how to evaluate. But that’s the dilemma about hierarchy and why is something good or better than the next. My philosophy is that no one can tell me what’s right or wrong.

Djordje Ozbolt: The Lord of Creation and Destruction