SANCTUARY OF CONFRONTATION

By Natsuko Odate

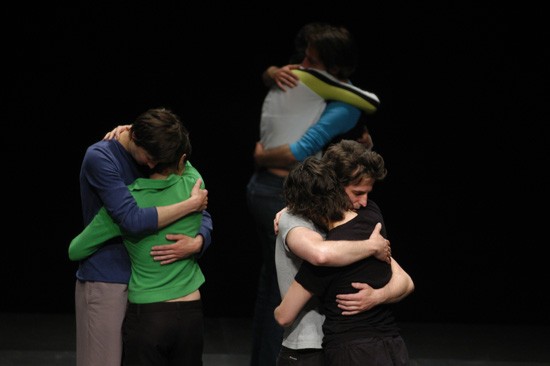

Theater Hora – Disabled Theater. Photo Michael Bause. All images: Courtesy Jérôme Bel.

In November 2011 Jérôme Bel came to Japan for a performance of The Show Must Go On, mounted at Saiatami Sainokuni Theater in conjunction with the annual interdisciplinary arts festival Festival/Tokyo. ART iT met with Bel at that time to learn about his plans for participating in documenta 13.

Interview:

ART iT: As a contemporary dance choreographer, you not only create performances for the stage but also participate in art exhibitions and collaborate with art institutions. In Japan, for example, you were included in the 2008 Yokohama Triennale. Is there any particular reason why you are so involved in the field of contemporary art?

JB: Recently I have been receiving more opportunities to work in the context of contemporary art, as with my presentation of The Show Must Go On (2001) at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and my participation earlier this year in the Tate Modern’s online project, “BMW Tate Live: Performance Room,” while at Yokohama I performed the piece Pichet Klunchun and Myself (2005).

Even with my participation in this year’s Documenta 13, I’m not exactly sure why I am invited to these events, so I myself find it surprising. It may simply be that contemporary dance is popular in contemporary art right now.

ART iT: I’m sure that is hardly the only reason. I think your approach to dance shares significant overlaps with how others consider contemporary art.

JB: Perhaps. My friend Tino Sehgal is known for creating performances for museum spaces, but I myself have no interest in such a project. I like the apparatus of the “theatre,” and have no interest at all in the apparatus of the “museum.” At a museum, the visitors come and go as they please, and the space is too bright. That is not the place for me. Strictly speaking this definition of the museum is certainly questionable, but at least it’s my personal understanding. As such I think of the museum primarily as a space for displaying documentation.

ART iT: So you maintain a clear distinction between museum and theatre?

JB: Yes. When I am in invited to participate in exhibitions, what I present are videos, specifically, recordings of my stage performances. It’s the same as when a museum displays the correspondences of an author: the display is not the work itself. For me the work exists only in the black box of the “theatre.”

Theater Hora – Disabled Theater. Photo Michael Bause.

ART iT: Is your project for Documenta conceived for a museum space, or for the theatre?

JB: Thanks to the efforts of the artistic director of Documenta 13, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, we have found a small theatre in Kassel for my use. It is a former cinema that was in fact designed by Paul Bode, brother of the founder of Documenta, Arnold Bode. It is a fantastic space, shaped like a cocoon. I will be premiering a new work there in that space.

ART iT: Can you provide specific details about the new piece?

JB: I will be working with professional actors who belong to Theater Hora, a Zürich-based company for actors with learning disabilities.

At this point I am still figuring out the details, but in the performance the roles of the group and of the individuals will be interchanged. In The Show Must Go On, the entire work was determined by the role of the group, or the community. It’s not that it was conceived in reaction per se, but my next work after that, Veronique Doisneau (2004), for the Paris Opera, isolated the role of the sujet in the ballet company. Some people who have seen the work think that I scripted everything for Veronique, but what she recounted on stage was entirely her own story, even though of course during production we were constantly working together.

The new piece will incorporate both those aspects. Where the actors usually work together as a group, they will be asked to step forward as individuals. There are among them those who cannot stand, or those who have trouble speaking, and I think these are important characteristics for the stage. But I am still not clear how it will all come together.

ART iT: Can you elaborate on the process that led you to pursue such a piece, and also on how you feel about presenting it in the context of Documenta, where so many artworks will be on display?

JB: On a trip to Kassel Carolyn took me to visit an abbey which was part of the Breitenau concentration camp during the war and is now a psychiatric clinic. She must have already had something in mind when she took me there, but in any case that experience will be connected to the new work.

I have no problem with these somewhat chance connections, but it would be disingenuous to say I had no hesitation about producing a project for an exhibition like Documenta. Tino Sehgal encouraged me to do it, and I agreed to participate on the condition that I could create a new project and that it would not be an installation but rather a performance piece.

During the three months that Documenta is on view, Kassel transforms into a culturally and intellectually extraordinary place. Held once every five years, the Documenta project itself is incredibly ambitious, and also non-commercial. But I believe that in bringing to such a context people with learning disabilities, who in a sense are not rational, it will be possible to raise questions about humanity itself, and how we define reason and culture. I have yet to decide the exact theme, but my piece will address the fundamentals of humanity and what it means to be human. I believe it will be a work of transparency, one that abounds with a childlike spirit.

ART iT: Can you clarify how you use the word transparency?

JB: I am opposed to the idea of control or manipulation. A theatre can be a site of control, but I myself prefer not to use it that way. Rather than hiding certain elements, my approach is to reveal everything.

Performance view of Veronique Doisneau. Photo Anna Van Kooij.

ART iT: Returning to my earlier question, Documenta is hardly your first contemporary art exhibition. When you participated in the Biennale de Lyon in 2007, you adapted The Show Must Go On into a kind of musical archive. How was that experience for you?

JB: To be frank, Lyon was a disappointment. It was there that I understood clearly my lack of interest in the museum. At the time The Show Must Go On was scheduled to be performed at the opera in Lyon coinciding with the Biennale, so I agreed to participate. In the mornings I was working at the museum, and then in the afternoons I went to the opera to work with the dancers, but working by myself at the museum was extremely tortuous, whereas in the afternoons everything would go smoothly and I was so pleased to be working with my team. That’s how I came to understand that I do not care for making installations and that I am not suited to the museum. On a deeper, unconscious level, I have a strong desire for the theatre, and cannot exist anywhere else. All my desires develop from that one desire.

I like working in groups and with communities, whereas the work of an artist is solitary. Sometimes I too like to be alone, but I dislike working by myself, even though there are people who call me an artist. Recently there has been an increased convergence of the fields of art, theatre, performance and dance. But even so my domain is within the world of contemporary dance. That is where I am rooted. I was raised on contemporary dance and people like Pina Bausch, Merce Cunningham, Trisha Brown and Yvonne Rainer. And beyond contemporary dance I was of course also influenced by Nijinsky. So it feels right for me to be a choreographer. Even when I am invited to participate in art exhibitions, I always think of myself as a choreographer.

ART iT: In that case what do you think of Tino Sehgal’s projects? In both his solo exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in New York (2010), and in works like Kiss (2002), he creates a kind of spectacle for the museum space, one that is conscious of the space itself. You say you have no interest in the museum, but can you articulate why you must work in the theatre?

JB: Tino is a very close friend, and I have the utmost regard for what he does. All his projects are wonderful and perfectly suited for the museum. But for me, why theatre? It is because there is time there. It’s not that I think time does not exist in the museum, but if visitors think a work is boring, they can walk away whenever they want. In a museum the viewer has complete discretion – and that is certainly one of the values of art and of exhibitions

But for myself I need some kind of enforced time. It is important for me to work within an apparatus that has been precisely determined in time, and where everyone can share the same time. You could say that in such a place it is not only the dancers, but the audience members as well, who form a kind of community.

In art the viewers are not generous with their time – and there is also the mystification of art. In the theatre, however, one can experience the passing of time in silence and tranquility. More than the time of viewing a work, I am rather drawn to the reality of having to pass a given amount of time in a determined space, as when – for example – flying to some place on an airplane. Personally the theatre is the place where I feel my self, as a viewer, to be protected.

ART iT: Yet even as you uphold the tradition of the theatre your works themselves are entirely avant-garde or, indeed, definitively contemporary dance. In other words, you pour yourself into creating a kind of dance that has never before existed. So it is surprising that you do not attack the system of the theatre itself.

JB: It’s true. I think I am influenced in that regard by Roland Barthes. I want to position myself within the tradition of contemporary dance. No matter how artistic or avant-garde the movements may be, it is all relative to the existing tradition. I still have faith in tradition and historical events. Rather than rejecting tradition, what I am doing is shifting it.

I also have a great love of Italian theatres. They are like red wombs edged in gold trim. The theatre functions as a space of security that has almost motherly qualities. At the very least it shields those inside from the outside world. And it is in such a space that fiction appears. Everyone knows that what happens there is not reality, which is precisely why I connect it with security. However terrible it may be, because we know it is not reality we can endure it.

I often say that I would be willing to kill in order to realize a scene that I am pursuing. This reflects the strength of my desire for my works in the theatre. In a museum, if something isn’t working, I try a few times to fix it but at some point I can easily let go. This never happens in the theatre. In the theatre I am constantly striving to create new things. Then, fortunately, I get more offers to do new works, and I can delegate responsibility for the old works to my assistants. People say with regard to old works that one should always monitor them, and take full responsibility in ensuring that they are performed as closely as possible to the original, but I do not live in the past. I live in the present. Naturally, I have a stronger interest in making new works.

Of course, a decade since it was first performed, I am still discovering new things in The Show Must Go On – new discoveries about my works, about my life, about theatre and about society. If not, there would be no sense in performing the old works.

Performance view of The Show Must Go On. Photo Mussacchio Laniello.

ART iT: How important is it for you to allow for new interpretations of your works?

JB: If people maintain an interest in my works such that 30 or 50 years from now they are still being performed, then obviously I would have to think up some kind of sustainable format for them. But I am simply not so interested in “preservation.” Everything disappears, so I think it’s fine to leave that process to nature. I still do not have an answer for it. For example, with classic ballet we try desperately to maintain the original form, but it has nothing at all to do with current social situations, and the stories are complete fantasies. Yet ballet is also part of history. I have no interest in the way that ballet exists, but on the other hand I understand it is important to think of some way for my works to be transmitted to future generations.

Currently I feel the best method is to record the performances on video. As videos, if there is a need the performances can be handed over to mediatheque and university collections. And then if someone has an interest in my works, that person has access to an entire video archive, and then he or she could even go so far as to restage the works based on the videos.

ART iT: But isn’t this similar to the way works are kept in museum collections?

JB: I hadn’t thought of it that way, but certainly you are correct. However, even being able to access my works through video, there is still nothing more important than seeing the live performances. With the development of the Internet and digital technology, there has been an unprecedented dissemination of all kinds of information, but nothing can replace the power – and ephemerality – of a live performance. Live performance is so important because it can resist the reality that is created by Hollywood special effects.

Disabled Theater premiered as part of opening activities of documenta 13 and will be presented for the public three times daily at the Kascade Cinema in Kassel on Sep 12-16. More information is available on the documenta website.

Jérôme Bel: Sanctuary of Confrontation