IN SOME WAYS IT IS AND IT IS INDESCRIBABLE

By Andrew Maerkle

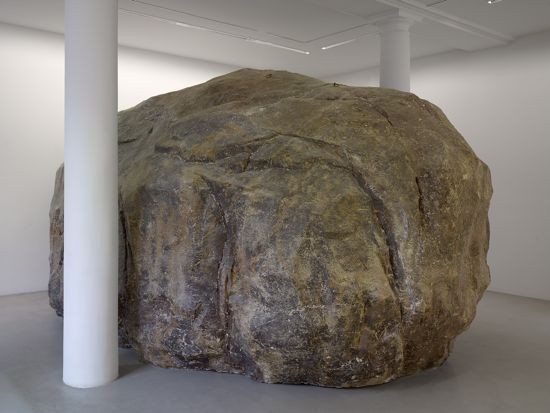

Caverne (2009), resin cave with sculptures of Buddha and Taliban figures, shadow projection, variable dimensions. Installation view in the exhibition “Caverne 2009” at kamel mennour, Paris. Photo André Morin & Marc Domage. All images: Unless otherwise noted © ADAGP / Huang Yong Ping, courtesy the artist and kamel mennour, Paris.

Interview:

ART iT: I’d like to begin with the Large Turntable with Four Wheels (1987) from the early period of your career, which was in a sense a device for escaping self-determination and expression. In preparatory drawings and notes for the Large Turntable it seems that the project involved relatively complex calculations and planning, or indeed a significant degree of self-determination. How did you envision your individual relation to the system that the Large Turntable ultimately represents?

HYP: The calculations for the Large Turntable were actually not so precise. The content of the turntable was all determined by chance methods, and the results of the turntable itself embody a kind of randomness. If you want to actually calculate how it all fits together, it would be quite difficult. Certainly the objective of the system was, as you just said, to address how an artist can escape self-determination, because all the operations of the system would be determined not by myself but by the turntable. I would say that I envisioned it as a way to minimize the individual decisions involved in any work. There was no essential relationship between one operation and the next. And of course whenever you spun the turntable, there would be no determining rationale in terms of where it stopped.

ART iT: At the time when you were preparing the Large Turntable, why did you want to escape from self-determination and expression?

HYP: My thinking was that what we believe to be most important about an artist is self-determination, but beyond a kind of mimesis this is always fundamentally restricted by the limits on which anybody can see himself. I had serious doubts about the idea that an artwork can be a representation of an artist. So with the Large Turntable it would be impossible to say whether whatever it produced could be considered a reflection of myself. I wanted to move beyond the discussion of art in terms of individual determination, style or thinking.

Left: Large Turntable with Four Wheels (1987), painted wood and mixed media, approx 120 x 120 x 90 cm. Right: Preparatory drawing for Large Turntable with Four Wheels (1987), watercolor, ink and photo collage on paper, 41 x 41 cm. Courtesy Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

ART iT: Was there anything specific happening, whether in China or abroad, to which you were reacting? Can you elaborate on the context for this interest?

HYP: What China lacked in the 1980s – and perhaps still lacks today – is self-determination. All matters were pre-determined; all thought was already formulated. The artists of the ’85 New Wave movement were hopeful that they could attain some kind of self-realization, but I found this to be a superficial issue. That is, we might describe contemporary society in the West as being “individualized,” but I question whether it’s even possible to have a fully individualized society. In the West today, can we really say that people have such a strong concern for individuality? On the other hand, with its predeterminations and restrictions, it might seem that it would be impossible for China to ever become individualized, which is precisely why the concept of individualization became so important there. In that sense individuality is a universal issue, and you could equally say it’s related to China in the 1980s or not related; you could equally say it’s related to the West today or not related, because it goes beyond a specific context. I was questioning the nature of self-awareness and the possibility itself for any kind of genuine individualization.

ART iT: But for example in the comprehensive retrospective organized by the Walker Art Center in 2005, “House of Oracles,” we could assume that all the works presented there ultimately represent the output and worldview of an individual artist, “Huang Yong Ping.”

HYP: In terms of production, the works investigate the nature of individuality, but individuality can be manifested in many different ways. Usually we think that a work is a representation of the artist who made it, and in a retrospective, everything that an artist has produced can be grouped under a single name. This is the implicit reality, there’s no denying that. But once a work is made it takes on a significance of its own. So even in a retrospective with all one’s works gathered together in one space, you could never get a complete view of the artist.

The House of Oracles (1989-92), installation with tent and related objects of metal, cloth, water, wood, brass, papier mâché, 320 x 480 x 480 cm. Exhibition view, “House of Oracles,” Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

ART iT: Then what about an installation like The House of Oracles (1989-92), with all the divination tools and objects gathered in the same space? What significance does such a work have?

HYP: First, I don’t consider The House of Oracles to be a work as such. It’s a display of the tools that I regularly used in my practice, or a display of the traces of various ideas. It’s not a “product.” It was a space for preparing the production of works. Of course once it was put on display it became something like a work. It’s a very contradictory situation, but I like that kind of ambiguity and complexity.

I made my own explanation of the work and why I want to use tools like the Large Turntable and the divinations of the Yi Jing (Book of Changes). But we can’t assume that that explanation is the final word on the significance of work. I feel that a work must go beyond the artist’s individual explanation. The artist’s explanation might lead you to your own understanding of the work, but it could just as likely mislead you.

ART iT: After you moved to France it seems your focus shifted from experimenting with chance operations to addressing specific issues such as post-colonial history and current events. Was this a big difference from the ideas on self-expression that led to the Large Turntable?

HYP: It was a big difference, and yet not. You could think about the problem this way. One is that we have no individuality, the other is that there is the multiplicity of individuality. Aren’t these actually the same issue? Multiplicity in a sense is the absence of individuality. After I moved to France in 1989 I decided that I would no longer use the Large Turntable as a tool for escaping individuality. Rather than using a specific tool I thought I could draw upon elements that emerged from different contexts and themes to produce all kinds of different works. This is a tremendous distinction from what I was doing in China. But in terms of practice both approaches actually ended up with similar results. I was now using multiplicity to revoke individuality.

Top: Bat project II (2002), sheet metal, 20 x 15 x 6 m, installation view 1st Guangzhou Triennial, Guangdong Museum of Art. Bottom: Colosseum (2007), ceramic, soil, plants, 556 x 758 x 226 cm. Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York.

ART iT: Can you explain how you understand multiplicity?

HYP: For me, multiplicity lies primarily in the differences between the works that I make. One day I could make one thing, the next I make something completely different. If you look at works like Colosseum (2007), made of ceramic, and the Bat Project (2001-05), with its life-size replica of the American spy plane that crash landed on Hainan Island, do you think they are the same or different? Maybe you could say they are similar at some level. But it is in their differences that they produce multiplicity.

ART iT: After moving to France, why did you want to add a narrative or symbolic significance to your works?

HYP: What we are discussing also applies to the multiplicity of significance, as opposed to just form. The less significance a thing has, counter intuitively, the broader its significance. If we see something and recognize that it’s black, there’s no real significance to its “blackness” beyond the fact that it is black. But if we start to think about what that blackness represents, then we imagine all kinds of completely different possibilities, from “death” to the simple idea that black is black. The same applies for red – we can see in it concepts like bloodshed or revolution but it could also just be the color red. These are completely different interpretations. So significance itself is the most extreme aspect of multiplicity. In a similar way my works contain all kinds of possible significance and symbolism, which can be interpreted in diverse ways.

ART iT: When you were still living in China it seems like you were already thinking about this issue. In 1988 you wrote an essay on Dada and Chan Buddhism in which you cited the Buddhist “Flower Sermon,” a famous example of wordless communication.

HYP: Yes. When Buddha grabbed the flower, his disciples reacted in different ways. One smiled, the rest had no response. The significance of the flower was produced from those different expressions and reactions. So this is another example of multiplicity. The “Flower Sermon” was a way to think about the issue of the Large Turntable from a different aspect, because the idea of the Large Turntable was also in a sense to escape signification. I wanted to consider the multiplicity of significance as the converse of individuality. For me, black can never be just black, or an object is never just an object. There is always another possible meaning.

Top: 11 June 2002 – The Nightmare of George V (2002), concrete, reinforced steel, animal skins, paint, fabric cushion, plastic, wood and cane seat, 243.8 x 355.6 x 167.6 cm. Exhibition view, “House of Oracles,” Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. Bottom: Caverne (2009), installation view in the exhibition “Caverne 2009” at kamel mennour, Paris. Photo André Morin & Marc Domage.

ART iT: So your early works are from one aspect addressing individuality, and from another aspect addressing significance, and both issues are interlinked. With later works like Palanquin (1997) and 11 June 2002 – The Nightmare of George V (2002), which symbolically address historical topics, what is the relationship with individuality?

HYP: When we talk about significance, we’re talking about aspects of a work that necessarily relate to society and politics, because to be significant means to be social. You could say works have a potentially infinite significance, because they necessarily take on significance in the minds of viewers. Palanquin evokes a number of issues of significance. A viewer might ask, who’s the person who carries the palanquin, and who’s the person who sits upon it? And maybe our projection of the kind of person who gets to sit upon the palanquin and the kind of person who has to carry it changes with each era. With The Nightmare of George V, too, you could say that the work is about the encounter between human authority and nature, and the intersections between nature and history. But these issues could just as likely emerge or not emerge from the work, and to the extent that significance exists in multiplicity, it necessarily involves a wide range of possibilities.

ART iT: And with works that touch upon current events, like the Bat Project or Caverne (2009), which has the figures of Taliban fighters sitting together with Buddha statues, do they not express some kind of individual political worldview?

HYP: You can’t say for sure that my political views are represented in works like that. Looking into Caverne, could you really say that I sympathize with the Taliban? Looking at Bat Project, could you really say that I’m opposed to or ridiculing the US? These works don’t express explicit views on these issues. The images they use are products of public controversy and dispute. They are not something I have created. So the significance of the work emerges from viewers asking why such images might appear in the works, and then deciding for themselves.

ART iT: Can communication take place through artworks?

HYP: From an abstract viewpoint wherever you place the work there will be some kind of communication, but the passage or route of communication between the work and the viewer can take all kinds of forms. Sometimes it is direct and at others it is indirect or obstructed. Some works are like open passages, seeking the approval and recognition of viewers. But communication also involves misinterpretation, so what the artist thinks may be an open passage could in fact be a closed passage for the viewer.

ART iT: Does an artist bear any responsibility for what an artwork presents to the viewer?

HYP: If I said that as an artist I take responsibility for what I say through my works, would you really believe it? If an artist says he speaks for a community or collective spirit, would you really believe it? Whether to have faith in what the artist says is the concern of the viewer, not the artist.

Top: Palanquin (1997), bamboo, cane, snake skin, colonial hat, cushions, 177.9 x 313.1 x 60 cm. Exhibition view, “House of Oracles,” Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. Bottom: Passage (1993-2005), iron, wood, light boxes, metal coiling doors, lion feces, animal bones, metal food bowls, cages 200.7 x 403.9 x 124.5 c, each, doorways 289.6 x 240.7 x 30.9 cm each, light boxes 36.5 x 133 x 17.8 cm each. Exhibition view, “House of Oracles,” Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

ART iT: Then what kind of communication is possible beyond signification? For example, in the story of the “Flower Sermon,” Buddha’s action of course bears no responsibility, because he’s just picking up a flower, but to the disciple who smiled, Mahākāśyapa, it nevertheless had a profound significance.

HYP: I think this is the difference. The person who grabs the flower and the person who sees that action exist in entirely different circumstances. In terms of responsibility, the artist is in the position of the one who grabs the flower, and is not in the position of the one who views the action. We can’t say that grabbing a flower requires any responsibility. He could just as easily grab something else. And even if he grabs a flower he could reject the interpretation of the person viewing the action. We should say that whether there is responsibility or not is like the relationship between presence and absence, with each contained in the other.

ART iT: So when an artist “picks up” the incident from The Nightmare of George V or the symbolic form of the Palanquin, is this not the same as picking up a flower?

HYP: Ultimately, just as it is impossible to say that the action of picking up a flower has no implication, if you want to believe that Palanquin has some kind of implication, that’s your view. The work is about the relationship between the one who carries the palanquin and the one who sits upon it. The one who carries it today could be the one who sits on it tomorrow, and vice verse. There’s no absolute behind those relations, just as there’s no absolute behind picking up a flower. They exist in a complete and fundamental relativity.

ART iT: Was this also the case for the work Passage (1993/2005), which you made at the Centre for Contemporary Art in Glasgow, with immigration-control-style gates for “EC Nationals” and “Others” installed next to each other?

HYP: Yes, that work was also about a kind of ultimate equivalence. Whether they chose to go through EC Nationals or Others, visitors going through both passages were required to pass cages filled with the feces and leftover food scraps from the lions at the Glasgow Zoo. It’s not like the entry for EC Nationals was lined with fresh flowers and the entry for Others with piles of excrement – that would have been a real distinction. Both entries were “different” but they were the same. Whatever the preconceptions one might have about which is better to identify with, both passages were equally smelly, and going through them visitors were entering into the same set of problems.

Huang Yong Ping: In Some Ways It Is and It Is Indescribable