PRODUCTION AND REPRODUCTION AND RELATIONS OF PRODUCTION

By Andrew Maerkle and Natsuko Odate

marxism today (prologue) (2010), HD video in color and black-andwhite, sound, 35 min. All images: Unless otherwise noted, courtesy Shady Lane Productions.

ART iT: In your works you have consistently addressed how subjects speak through pop culture and information frameworks such as karaoke, news programs and reality television. At first glance your ongoing marxism today project seems to establish a different approach to these earlier works. Can you explain more about how the marxism today project came about?

PC: Many of my projects are based on the question of what kind of encounters can be provided by art. Art is exciting in that it’s still not entirely circumscribed by the regimes of other commercial products, like TV or film. Somehow art still has a degree of autonomy, and is one field in which people are prepared to engage in an unusual relationship, whether it’s singing at karaoke, taking their clothes off in a hotel room, or reality TV victims speaking about their experiences to the press. In my case, these acts are usually structured in ways that are manifestly uneven: they are not utopian in their motivation; it’s not about everyone being equal, but rather staging something that is barbed or difficult in its nature.

I went to college in Manchester in the late 1980s and early ’90s, around the time of acid house and the explosion of rave music that happened there, and then continued my studies in Belfast in Northern Ireland, which had a different political geography. So pop culture and politics have always been closely entwined in my mind. At the end of the 1990s I began working in and around ex-Yugoslavia, in Kosovo and Serbia, as well as in the Middle East, in Iraq and Palestine.

marxism today comes from that lineage of my interest in how representation speaks about socially repressed histories. The former East Germany has experienced an erosion of its symbolic legacy, which has been supplanted by unified Germany’s reappraisal of it, usually articulated through two specific frames: the Stasi secret police and the terror of the state. This is problematic because it doesn’t seek to reflect the lived experience of socialism. Of course it was an authoritarian regime, but that doesn’t fully account for people’s reading of their own lives.

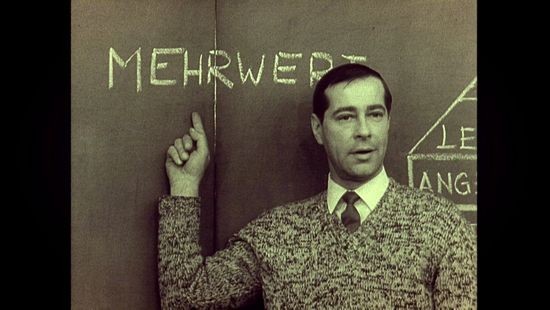

I was in Berlin for the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, and there was a big exhibition on Alexanderplatz attempting to encapsulate the effect of such an epochal event on different social groups. It featured everybody, from punks to dissenters to the Protestant Church. But I started wondering about what had been left out. In the West, Marxism is seen as a radical position – Che Guevara, 1968 – but in East Germany, and other Soviet satellite states, it was, of course, the orthodox position. What was it like to teach Marxism as the state ideology at the moment when the state was collapsing and the economy was bankrupt? How might that perspective shed light on the past 20 years? For marxism today (prologue) (2010), we spoke to 60 former teachers of Marxism-Leninism, filmed 10, and in the end I focused on three that I used for the film.

Both: use! value! exchange! (2010), HD video, sound, 21 min.

ART iT: Especially for the German audience there must be a very complex mix of emotions and associations, including a degree of nostalgia. Certainly at the 6th Berlin Biennale in 2010, when I saw marxism today (prologue) there seemed to be a profound response among the viewers.

PC: I think rather than nostalgia, it is more a certain sense of sympathy that the viewers identify with. I didn’t try to make the film’s subjects any less complex than they were. I wanted to include all their contradictions, their personalities, whether they were likable or not – but all their stories have strong narrative arcs so it’s not difficult to establish an emphatic relationship.

For the second film, use! value! exchange! (2010), I asked three of the teachers to give a lesson in Marxist economics to current business students in Berlin, as they would have taught it in 1989. The interesting thing about Capital is that it’s not a program for a revolution, but simply Marx’s reading of capitalism. It’s an analysis of consumerism and the consumer object – what it means to trade, what is use-value, what is exchange-value, and so on. Moreover, Engels ran his father’s factory in Manchester for 22 years. He was a capitalist by day, and a radical by night. The two based their research on Engels’s factory: the mechanics of how the factory functions, how capital circulates. They’ve been reduced to one-dimensional characters by the state-socialist dogma, but their biographies are very divergent because they were both strategic in their lives, and not as evangelical as one might imagine.

The idea for the continuation of marxism today is to make a film bringing teachers to teach Marxism at schools in Manchester, partly because of the connection with Engels, but also because Manchester was the world’s first industrialised city. With the Industrial Revolution, Manchester became both hell on earth and an elaborated representation of what capital could be – the site of both its birth and its resistance, as well as of the formation of the factory system, which of course has moved on to countries like India and China.

But it was a really interesting project to do specifically in Germany because it touched on the fault lines of what people speak about and how they remember, which versions of history become un–articulated or disowned.

Top: shady lane productions (2006), production company and research office, installation view, Turner Prize 2006, Tate Britain, London. Photo Sam Drake & Mark Heathcote. Courtesy Shady Lane Productions & Tate Britain. Bottom: the world won’t listen (2004-07), installation view, Marabouparken, Sunbyberg, Sweden, 2011. Photo Jean-Baptiste Béranger, courtesy Shady Lane Productions and Marabouparken.

ART iT: A number of your works have a self-referential aspect, as with the press conference that was part of the project shady lane productions (2006), where the staging itself is staged. With the marxism today films was there a similar mechanism in effect?

PC: No, I think it is different. Many of the projects complicate the idea of redemption. You come and tell the story of your maltreatment by reality TV to the press, but nothing is resolved. With marxism today (prologue) I knew the question would be interesting for a German audience, but also that it would be difficult to find people. I put adverts in women’s magazines, socialist newspapers and small local press, and more than a provocation it was formulated as an issue of mutual interest. With other projects, sometimes the pain of the encounter is erased by the beauty of the delivery. In the case of the world won’t listen (2004-07), taking a Smiths karaoke machine to Columbia, Turkey or Indonesia is quite problematic when you are laying out the terms of engagement to the singers. However, once karaoke becomes a conduit for misreadings of Britishness or British pop culture, it is no longer about ludicrousness but about something more noble. And, of course, there is a performative element to nationality itself. The English perform Englishness every time they drink a cup of tea.

With use! value! exchange!, in which the lesson is given to the students, that is obviously a staged situation, more like an experiment or a historical reenactment. I was curious to see, when the language is not used for 20 years, how fluent or persuasive could it be, or would there be a divide between the teacher and the students. What amazed me was how little of a reenactment it was and how much more a rearticulation.

ART iT: With the explosion of information that is now available to us it feels as though the idea of archaeology – as the recovering of history – is more pressing than ever. The idea that you still have at your disposal someone who has lived through a different phase of history other than what currently predominates and who could recreate that is fascinating to me, and I assume it would be fascinating to anybody studying economics in Berlin. Do any of your other works have this archaeological aspect?

PC: I’m not sure if I would apply the term “archaeological” to working with people. What I’m mostly interested in is finding subjects who could, in different ways, be considered as having been left out. In so much contemporary art there is an underlying impulse of the artist looking for their own mirror–image, for making work with or addressed to their own socio–economic group. I find this abysmal, when there’s a whole world of people out there who could answer your question in ways that you couldn’t imagine or might not even hope for. What would a Palestinian disco dancer look like after dancing for eight hours? What happens when, instead of consumer products, you purchase a fantasy in a teleshopping program? For me, it’s about getting as close as possible to the actuality of a situation – not to represent something or reorder it, not as a gesture or a speculation towards it, but to create the “thing” itself as it operates within the social field. You invite someone to the karaoke machine, you press play and it works just like any other karaoke machine would. I try not to look at fictions but at moments of experimentation, and they’re usually articulated through the popular and the vernacular rather than through the Modernist strategies of defamiliarisation and disconnect. They are artworks that don’t necessarily recognize themselves or ask to be seen as such.

Pt II

Phil Collins: Production and Reproduction and Relations of Production