III. Advanced: Yishmór, Tishmór, Tishmór, Tishmrí, Eshmór, Yishmrú, Tishmórna, Tishmrú, Tishmórna, Nishmór

Ming Wong on future developments in his work and representing his nation at Venice.

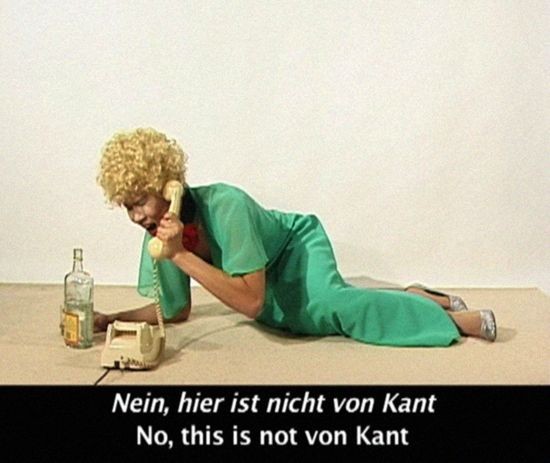

Video still from Lerne Deutsch mit Petra Von Kant (2007).

Video still from Lerne Deutsch mit Petra Von Kant (2007).ART iT: We were just discussing the relationship between audiences and your use of cross-dressing as a technique to exchange not only gender roles but also societal or cultural roles as well. This reminds me of Volker Spengler’s performance in Fassbinder’s In a Year of 13 Moons (1978), in which Spengler plays a transsexual woman. Your first impression of him is that he’s clearly a man, but as you watch the movie you get sucked into the performance. So even though he’s clearly a man, he’s also clearly a woman. It’s more about the actor’s conviction than what the audience sees.

MW: Yes, and also sometimes it’s more complex than that. Sometimes viewers will look at me and think not just, “He’s not a man or a woman,” but also, “He’s Chinese! He’s not an Italian mother!” That also throws people off. Or the fact that I’m saying the lines wrong, because I’m not an Italian speaker and I’m mangling these really famous lines and there are all these irritations.

I always ask people for their reactions to my work and one interesting thing that I was told about Angst Essen / Eat Fear is that everybody in Germany knows Brigitte Mira, who played the housewife in the original film. So when they see me playing her role, of course they have all these irritations, but after a while they begin to suspend their disbelief, they get beyond their preconceptions, and they begin to focus on the words, on the original script itself. Perhaps more so than when they watch the original movie – because then they are distracted by other things, like Brigitte Mira and how well she acts, or how good the movie looks as a whole – they don’t actually pay attention to what the characters are saying. Somehow through my works they get past all of that and can reconsider the original material. That was an unexpected and actually good reading and I hope that I can continue to do that somehow.

ART iT: Where do you see your work developing from here? Do you think you’ll continue with this idea of recreating World Cinema?

MW: I think it’s still going to be a personal journey, so I’m just going to follow my own path. I am going to do something in Istanbul, a personal pet project that I’m trying to start up. I think it’s linked to being in Germany and having made the Angst Essen / Eat Fear piece and the issues around it, and the fact that Turkey is in transition. It’s always been the last frontier between Asia and Europe and now it’s joining the EU. I think the idea of what constitutes Europe or Asia is a rich topic, and Turkey has this duality of extremes that attracts me. I’ve been looking at the film history there and the popular culture, which is very unique. Turkey has a history of “poor imitation” similar to that found in the Singapore film industry, and also religious issues reminiscent of Malaysia. But beyond that Turkish films have something totally unique, which is a strong sense of melodrama in the expression and the music. I cant be any more concrete than that – I’m still researching. But that’s one area that interests me.

ART iT: Would you consider working with American or British films?

MW: The problem with many English-language films is that by default they constitute the so-called mainstream, and are not considered World Cinema. All the films in the world get packaged into either World Cinema or Hollywood mainstream, and I think that’s not accurate. It’s not that I try to avoid Hollywood. There are some films that I really appreciate. Imitation of Life (1959) is one of my favorite films, and I used it for my Singapore Pavilion project, although the director Douglas Sirk was in fact German, and influenced Fassbinder and Wong Kar-wai.

So there are all these links. I don’t necessarily target foreign-language films, but because everything is so globalized these days, everybody watches films from all kinds of countries. I gravitate toward films from times that were politically interesting in their respective countries.

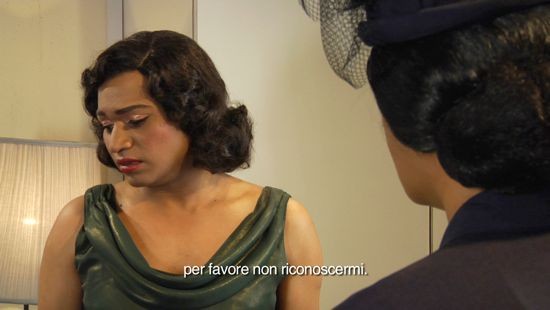

Above and below: Video still from Life of Imitation (2009). Middle: Installation view of “Life of Imitation” in the Singapore Pavilion at the 53rd Venice Biennale, 2009.

Above and below: Video still from Life of Imitation (2009). Middle: Installation view of “Life of Imitation” in the Singapore Pavilion at the 53rd Venice Biennale, 2009.ART iT: Have you ever thought about making an original story or a feature film, rather than referencing an existing work?

MW: I do think about it, although I don’t believe there’s anything that is 100-percent original. It’s like they say about there being only three or so story templates in the entire world.

I believe in journeys. One dream project is to go to China, which would be another step in my personal journey. A lot of things are happening there now and for me there’s an added layer of significance given my ancestry. I want to climb Yellow Mountain because my Chinese surname means “yellow,” and it would be this metaphorical pilgrimage of climbing up a mountain.

I think I will eventually do something that is not obviously derivative of an existing work. The works that I have used so far are markers, which is what every person needs as they progress in their lives. You have to latch on to something that eventually should lead to your own milestones. I’m very conscious of that. When am I going to make something “original”? Maybe something original comes out of doing these imitations, in the sense that I relinquish a degree of control over the process.

ART iT: How do you relate to Singapore, especially after winning a Special Mention at the 2009 Venice Biennale?

MW: How do I relate to Singapore? How does Singapore relate to me? I’m a national hero! I have to say in certain ways people are now taking an interest in me as an artist. For a long time I was known as the guy who wrote Chang & Eng the Musical.

I think Singapore’s going through an interesting phase, a transition with population change and how it affects national identity. Its conversion into a casino city with this year’s opening of the Marina Bay Sands development is going to have a big impact on national identity. So I’m interested as an observer.

ART iT: I read an article in the Straits Times about the Venice prize and it seemed that the attitude toward culture in Singapore is very results oriented. The writer noted that the Special Mention is Singapore’s first prize at Venice even though the country has already been exhibiting there since 2001.

MW: To an extent it’s understandable, but talking to the bureaucrats who worked at the National Arts Council at the time, that really is the mentality. It’s like they don’t really care about the artists, they want to take credit for their own work, you know, “Finally this has happened because I’ve been in charge for five years.”

It’s totally results oriented. They’re pumping money into the arts but it’s a military exercise. I think even some of the ministers of the arts are in fact from military backgrounds. So it’s a balancing act.

ART iT: Did you have any disconnect exhibiting in the national pavilion after spending so much time in Europe?

MW: Not at all. In fact, I think this was the first Singapore Pavilion that dealt very directly with Singapore history. Maybe you could also count Lim Tzay-chuen’s proposal in 2005 to bring the Merlion monument to Venice, but in other years it’s largely been artists making artwork. The pavilion curator Tang Fu Kuen and I decided to deal with the idea of a Singapore Pavilion and what Singapore is. For example we included in the installation a map of Southeast Asia because so few people actually where Singapore is.

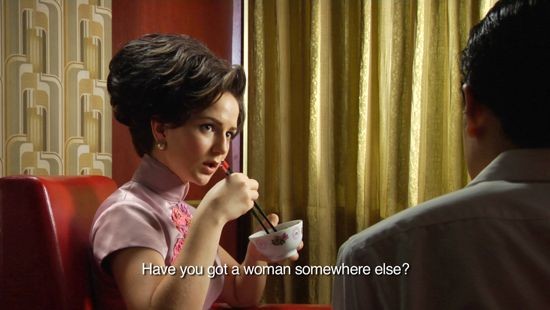

All: Video still from In Love for the Mood (2009).

All: Video still from In Love for the Mood (2009).ART iT: Of course, one of the jury members at Venice was the post-colonial theorist Homi Bhabha. Did you talk with him at all?

MW: A little bit. I remember he said very proudly to everyone around us, “These are my children!” You could also see the jurors planting their agendas a little bit. In the official awards listings, each prize was given a title – mine was “Expanding Worlds” – and a blurb. My blurb was quite peculiar, something about “shame” and “impositions of racial and sexual stereotypes,” and it made my project sound like it was coming out of a very repressive context, when in fact what we did was celebratory. So sometimes what the post-colonial mindset lacks is a sense of humor. I’m not saying the Singapore situation is fine and dandy, but there was an element of joy in the pavilion that they missed.

ART iT: Have you ever been tempted to do something more critical, like a Fassbinder-style approach to working with Singapore?

MW: My philosophy is that you thrust deepest when your enemy is off guard. There are many artists who make critical works in Singapore, but because the work is critical from the start, it actually limits the capacity to be meaningful, because it’s too literal. In fact, there was a lot of critique couched in the whole Singapore Pavilion. The NAC weren’t fully aware of what they were in for, they just saw the signs that it was promoting heritage and it was self-glorifying, but the installation was about what happened in those years since Independence and what we have lost.

You have to be reflexive as an artist in Singapore because inevitably many critical works are funded by the very government they criticize. It’s a tricky issue. In 2003 when the filmmaker Royston Tan came out with his feature-length film 15, about teenaged petty criminals and drug runners in Singapore, he was branded and sold overseas by the government as Singapore’s “rebel filmmaker.” He was the state-sanctioned rebel. It was unusual, because in the publicity they literally had a line like “Singapore’s Rebel” or whatever. It was in the marketing and I found that a bit disturbing. I sympathized with Royston. It’s a paradox, but it’s the government’s way of promoting themselves. So as an artist you have find a way out of that cycle of dependency.

But I do plan on making works in Singapore. I have a support system there with collaborators, and it’s hard to build up a good team. It’s also a source of inspiration. I think I make all of what I do because I come from Singapore, and lived there through a certain period in its history, and that continues to define me.

Ming Wong‘s solo exhibition “Life of Imitation” is currently on view at the Singapore Art Museum through August 22. Wong is participating in the upcoming 8th Gwangju Biennale, “10,000 Lives,” at multiple venues in Gwangju from September 3 to November 7, and his solo exhibition, “Gruppenbild,” opens at the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein on September 28, continuing through November 5.

All images courtesy the artist.

Cover image: Video still from Devo partire. Domani / I must go. Tomorrow (2010).

Cover image: Video still from Devo partire. Domani / I must go. Tomorrow (2010).