COMPLICIT CONSCIOUSNESS

By Andrew Maerkle

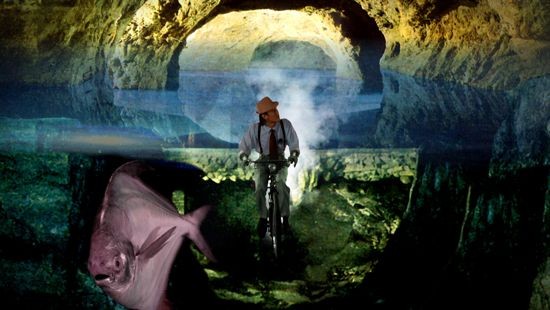

Still from Doghole (2009), HD Video, 22 min. All images: Unless otherwise noted courtesy Wong Hoy Cheong.

Still from Doghole (2009), HD Video, 22 min. All images: Unless otherwise noted courtesy Wong Hoy Cheong.Born in Penang in 1960 and now based in Kuala Lumpur, Wong Hoy Cheong explores a diverse range of approaches and topics in his multi-disciplinary practice. His works often contain political undertones, regardless of whether they address Malaysia’s colonial legacy, its contemporary society or overlooked strands of international cultural history. Yet they also entertain, as in the project RE:Looking (2002), which imagines a 250-year-long discreet Malaysian imperial rule over Austria as seen through a fictional BBC-style self-regarding investigative TV program, or in the photo series “Chronicles of Crime” (2006) and “Maid in Malaysia” (2008), both of which borrow the glossy sheen of Hollywood promotional campaigns. Such works critique not so much particular issues or agendas but rather the mechanisms of art and media, and how representation inevitably appropriates, distorts and obfuscates the political relations of agency. Wong talks about this effect in terms of complicity, implying that for him there is no purely critical perspective. Instead of simply pointing to an objective problem, the transformative action in his works lies in getting viewers to recognize this complicity, and acknowledge the unquiet irony through which we distance ourselves from life’s complications.

Over the course of two sittings in 2010-11, ART iT met with Wong to discuss the ideas behind his works, as well as his multiple careers as artist, educator and political activist.

Contents:

Part I: Theatre of Incident

Part II: Theatre of Consumption

Part III: Theatre of Transformation

I. Theatre of Incident

Wong Hoy Cheong on his mis-education in art and the intersections of lost histories.

Installation view of the mixed-media and video work RE:Looking (2002) at Eslite Gallery, Taipei, in the exhibition “Days of Our Lives: Selected Works 1998-2010.”

Installation view of the mixed-media and video work RE:Looking (2002) at Eslite Gallery, Taipei, in the exhibition “Days of Our Lives: Selected Works 1998-2010.”ART iT: This issue addresses the theme “Education/Pedagogy,” looking both at artists who are involved in education as well as the idea of contemporary art as a performance of auto-didacticism. You have said previously that you stumbled into art and it was never particularly your intention to become an artist. In this sense it seems like your story begins with a mis-education. Can you talk more about that experience?

WHC: Yes. I was one of those confused 17-year-old kids who went to college and had to write down a major because he had to have a major, so at first I wrote down biochemistry because I thought, “Wow, this will make me lots of money.” But I hated organic chemistry and from there I migrated to various disciplines – urban planning, psychology, this and that – and ended up studying literature with a Frankfurt School, critical theory bent. Then I went to the Graduate School of Education at Harvard, and there I was influenced by the ideas behind developmental education, particularly the Brazilian educator Paulo Freire’s pedagogy of “conscientization.” From there I wanted to continue on to Islamic studies because I had also studied Arabic at Harvard. I applied to study in Cairo, was accepted, but didn’t get a scholarship. At the same time, I was interested in art, so I had also applied for a course in art. When I was accepted into the MFA program at the University of Massachusetts (Amherst) with a scholarship, I ended up there. It was quite incidental in a way. It was not that I didn’t like art – I liked it – but I wasn’t thinking of it as a career. Up to that point, I was very excited by ideas, and had been doing intensive academic programs, writing up to a paper a week.

ART iT: For a late starter you’ve gone on to make many pioneering art works, both in a Malaysian and in an international context.

WHC: Maybe. I don’t know if I’m responding to that experience. Perhaps it’s because of my academic background. As I grow older I have begun to see the connections between literature, critical theory, pedagogy and visual arts much more clearly. In much of my work I do refer to my interest in the history of ideas and pedagogy. My academic background has actually been very useful. It took me a while to figure it out but it gave me a broader and deeper notion of art making.

When I discuss art I often interrogate the complexities and complicities involved. For example, in the early 1990s I taught a course on third-world aesthetics that was very much influenced by the ideas of Freire as well as Augusto Boal’s ideas on theatre as a political action of the oppressed. I was interested in asking: is there such a thing as third-world aesthetics? I used the class as an arena to think through some of these ideas together with students. But I stopped teaching it after a few years because I came to realize that often there’s a thin line between third-world nationalism and fascism and authoritarianism, and that while meant to be liberating, “third-world aesthetics” also had a strong nationalist agenda to it that could easily be co-opted. These different relations are all so slippery.

ART iT: How did you go from making paintings to installations and new media works?

WHC: I did my MFA in painting and studied with a few second-generation abstractionists, particularly John Grillo, who was a student of Hans Hofmann. I was heavily influenced by Hofmann’s theory of “push and pull,” but by the time I returned to Malaysia I was making around only two paintings a year while the rest of the time I was involved in NGO work. I no longer found painting to be effective. I didn’t like the smell of turpentine; I didn’t like the labor of working in oil paint, the lack of immediacy. I stopped painting and began trying all kinds of media like video, performance art, installation.

ART iT: Were you already familiar with these approaches when you started them?

WHC: No, and that was the nice thing. Precisely because I was not trained with formal strictures, it made it easier for me to experiment. I think simply being away from painting – especially Hofmann’s theories – was very liberating for me.

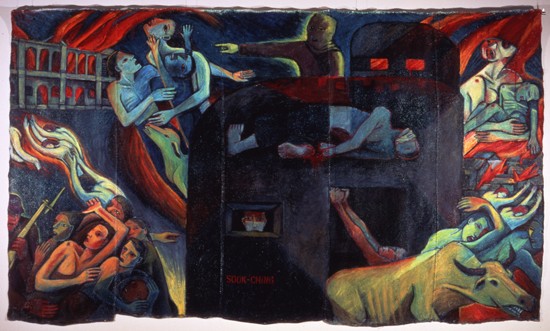

Top: Sook Ching (1991), oil on gunny sac, 213 x 366cm. Bottom: Sook Ching (1989), video, 27 min. Both: Collection of Fukuoka Asian Art Museum.

Top: Sook Ching (1991), oil on gunny sac, 213 x 366cm. Bottom: Sook Ching (1989), video, 27 min. Both: Collection of Fukuoka Asian Art Museum.ART iT: Did you find that painting also restricted the issues you could deal with as an artist?

WHC: Yes. For one it was too solitary. Because of my NGO background I was accustomed to collaboration and working in groups. I felt painting restricted the potential for collaboration. In one of my last paintings, Sook Ching (1991), I explored the Japanese Occupation of Malaya in World War II. The work was a painting but again because of my academic background I did preparatory archival and historical research. I was interested in oral history so I interviewed survivors of the Occupation, and recorded those interviews.

Through this experience, I felt there was an element missing in the final painting. It was gestural and personal, but it didn’t have historical depth – the faces, the expressions, the voices of real people. This led me to make my first video. But after I did the video I realized there was a live and visceral aspect to the human body that was lacking in the video. This made me think of performance as a possible component of the work. I worked with some performers and the final project involved the painting, the video and performances. I learnt a lot in the process of realizing this project.

ART iT: What does the painting look like?

WHC: It’s a mixture of, I guess, Mexican Mural Art and American Social Realism, a bit Cubist or Guernica-like, if you will. The video consisted of historical footage, documents and survivors speaking about their experiences. The performance was confrontational, challenging the audience through movement, gestures and voice. We had five main performers as well as others planted in the audience who made accusatory gestures at the spectators and at each other. I guess in times of war, complicity and indiscrimination can be rife: accusations and counter-accusations, victims and oppressors are bound up into each other’s existence.

ART iT: So there was an interpretive element with the painting, an archival element with the video and a live element with the performance, all presented in the same space?

WHC: Yes. It was kind of experimental, but looking back I would say it’s a bit simplistic because the painting became a backdrop for the whole event, whereas the video and the performance fit together better.

Top: Installation view of Trigger (2004), multi-channel DVD projection, commissioned by Liverpool Biennial International 04. Bottom: Still from Aman Sulukule, Canim Sulukule / Oh Sulukule, Darling Sulukule (2007), video, 13 min 52 sec.

Top: Installation view of Trigger (2004), multi-channel DVD projection, commissioned by Liverpool Biennial International 04. Bottom: Still from Aman Sulukule, Canim Sulukule / Oh Sulukule, Darling Sulukule (2007), video, 13 min 52 sec.ART iT: From exploring video and performance you have gone on to use unconventional materials ranging from plants to cow dung and paper and food. But it seems that one recurring theme for you is the history of colonization. Would you say this is something to which you conscientiously return?

WHC: I am certainly lured by the properties, textures and meanings of unusual materials. Colonialism – post-colonialism – is a sub-theme in my work. I think I am more excited by and interested in retrieving lost and forgotten histories, marginalized narratives – and also challenging notions of authenticity, official narratives: what is it that constitutes authenticity? Authoritative truth? I’m interested in prying open these assumed axioms and dictums to see what hovers behind and beyond.

ART iT: Is this an issue rooted in your experience in Malaysia itself or is this an issue you address as a Malaysian artist who is also involved in international contexts?

WHC: I think all contexts can be interrogated. The retrieval of histories, especially marginalized histories, is quite global – relevant to all societies. History for me is often contingent on who has power, who can decide what goes into the narrative, and marginalized communities often do not have “civilizations” or “histories.”

When I do commissions overseas I’m particularly interested in these slippages of histories. Often they are nothing big or grand. For example, for the 2004 Liverpool Biennial I was interested in retrieving pop history, so I made a film reenacting the iconic American singing cowboy Roy Rogers’ first trip to the UK following World War II, which coincided with the entrance of American popular culture there. We wired a horse with multiple cameras to recreate the point of view of Rogers’ dancing horse, Trigger. Previously, the audience was the voyeur of this spectacle, but the horse became the voyeur in the video I made.

In Turkey for the 2007 Istanbul Biennial, I worked with the Roma community – oppressed and marginalized since Byzantine times – to make a film of stories, fantasies and song, Oh Sulukule, Darling Sulukule. So I’m not particularly bound to addressing political or historical issues in a strict way.

Wong Hoy Cheong: Complicit Consciousness