Hic et Nunc; or, The Delirium Beyond Translation

By Andrew Maerkle

Working effortlessly between canonical, alternative and esoteric sources, Cerith Wyn Evans draws upon a broad knowledge of literature, linguistics and even astrophysics in his conceptual art practice. At times sensational, at times inscrutable, his works rarely reveal themselves at first glance. Instead, they often playfully fragment or distort information in a way that provokes viewers’ awareness of the complexity of reading. His series “Chandeliers,” for example, converts literary texts into Morse code that is transmitted through the blinking lights of programmed chandeliers, while for the piece F=R=E=S=H=W=I=D=O=W (2010), he cut out all the text from Stéphane Mallarmé’s notoriously untranslatable poem “Un coup de des jamais n’abolira le hasard,” leaving blank spots in the framed manuscript pages on display. Such works are reminders of the fickleness of “face value,” as underscored by the title of his 2007 exhibition at Tokyo’s Taka Ishii Gallery, “Futa Omote (double face).”

Evans visited Japan in August for the opening of the inaugural Aichi Triennale, for which his neon text piece 299 792 458 m/s (2004/10) beams a cryptic, cosmic message from the rooftop of an office building in downtown Nagoya. ART iT met with the artist in Tokyo to discuss his relationship with language and his referencing in his works of artists ranging from Pier Paolo Pasolini to Marcel Broodthaers.

I. We Turn in the Night, Consumed by Fire

Cerith Wyn Evans on theories of translation, non-understanding, intimacy and ‘awe.’

Installation view of ‘…in which something happens all over again for the very first time’ at Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris/ARC, Paris, 2006. Photo Marc Domage, © the artist, courtesy Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris/ARC, Paris.

ART iT: You are known for frequently citing literary texts in your works, transforming them into Morse code in the case of your ongoing series of programmed “Chandeliers,” or using fragments of text as the basis for neon signs, for example. Thinking about your works in relation to the context of literature, do you consider them to be a form of translation?

CWE: That’s a hugely loaded question for me. Yes, I do – in the sense that I’ve been investigating theories of translation for as long as I can remember. English is not my first language, Welsh is. To that extent, the entire balance of meaning is predicated for me on the process of translation. Not only is it a kind of mediating force between two separate languages, the very prefix “trans,” as “otherness,” is absolutely central considering that I have worked with many codes and forms of languages and sublanguages. In fact I am so obsessed with the subject of translation that I have a top-10 list of translators, some of whom don’t even translate from languages that I understand. If a translation is to be understood as a slave to the master text, then it has to be sensitive in a way that is deeply creative; programs like Google Translate are just rubbish.

My favorite theoretician of translation is Martin Prinzhorn, a former pupil of Noam Chomsky’s and now a structural linguistics expert at the University of Vienna. I admire him because of his intelligence and his sensitivity. I admire him because of his subtlety and his way of detesting fascism, actually. He wrote a short text about my work in relation to theories of translation when I did a solo exhibition at Kunsthaus Graz in 2007. We spent many days together talking about it, arguing about it, trying to articulate what that relation is.

The question of the future of translation is very interesting to me because language is a constantly evolving source of communication between people. I’m not a cynic or a pessimist in this respect, but I do think that forms of communication have changed irrevocably in the past 20 years. We are constantly mediated thorough information technologies that have changed the fundamental structure of what it is to communicate and to speak to another person. It drives me crazy sometimes when the phone is ringing and someone is sending an SMS and it’s all in this compressed form. It makes me reach for the Confessions of Saint Augustine, or Marcel Proust, or Jane Austen, or any of the many authors that have been incredibly nourishing to me, and strange and wonderful.

I don’t think there are many theoreticians writing about language technologies who can articulate what’s happening right now. The critical theory in and around the revolution that’s taken place in very recent times is still in its infancy. The phone number of my childhood home had only four digits, 3-2-0-5. That feels like another universe.

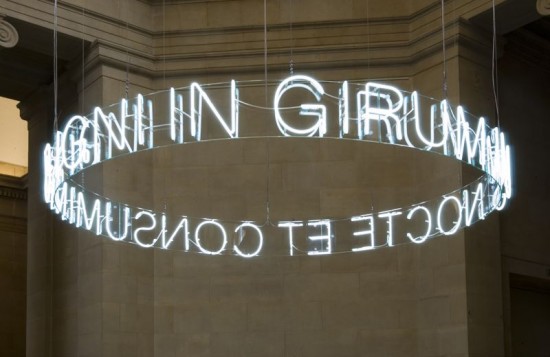

In Girum Imus Nocte et Consumimur Igni (2006), neon. Installation view © Tate 2006, courtesy the artist, Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, and White Cube, London.

ART iT: It seems that before the age of communication technology as it’s understood now, the issue with translation was mostly the idea of the translator as traitor – “traduttore, traditore” – and the impossibility of a true translation. Would you say that the traitor now is the very media of communication?

CWE: I think I know the territory that you’re speaking around. Most people want to be loved, and a very tender form of accurate communication is to ask these very sensitive, very subjective questions. “Do you love me?” is a huge question. Now, as far as I’m concerned, that’s bound up with very primal forms of communication. Because you actually have to vocalize and enter into the space of language in order to be able to speak, how do you translate that? There are many forms of non-spoken language that are also language. I don’t mean just music, dance, architecture. There are many ways to actually communicate without using written or spoken language. There’s intimacy for instance. That’s language too.

The mediamatic has existed since language has been written. I think Gutenberg is a mediation that is an absolute ur-betrayal, if you like. The historical development of religious texts is what put a space between communication and the medium that was possible to employ. I don’t want to feel cynical and depressed about the fact that there is less availability. I’m an enormous fan of all sorts of people who are deeply cynical like Guy Debord. I’m a great admirer of the script for his film In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni (1978), and have referenced it many times. I think it’s an extraordinary, brilliant and super passionate text. But I think there are points at which we should remain optimistic about the moment of communication that can, for instance, communicate compassion. I’m not so technical in and around language. I’m actually very emotional in and around it. Can you imagine not being able to speak?

So, I count my blessings, and Welsh is a big blessing. I’m jealous of people who can communicate. One of the things that is fascinating for me when I come to Japan – and I was just thinking the other day that this is my 21st visit here – is that there are certain freedoms available when one is confronted by non-meaning and non-understanding. I’ll give you an example I’ve used before. There is a great architectural theorist, Mark Cousins, who works at the Architectural Association in London. In the mid-1990s he described an exhibition of mine as being so perplexing that it was like the experience of a deaf man staring at the radio. I took that as a compliment, not because I want to be willfully obscure, but because I want to engage in the territory where radical, new forms of communication are possible. Guy Debord says, “In languages yet unspoken and unlearned.” We don’t know what the future of communication holds. When will we first contact alien life forms? I’m sure it will be fairly soon. That will blow the lid off the firework box. But the history of human communication is actually extremely brief. Gutenberg was only a short time ago.

‘La Part Maudite’ by Georges Bataille (1949) (2006), chandelier (Luce Italia), flat screen monitor, Morse code unit and computer, dimensions variable. Photo Stephen White, © the artist, courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, and White Cube, London.

ART iT: You mentioned that you grew up confronting issues of translation because English is your second language. As I understand it, it was a trip to Japan that inspired you to start making the “Chandeliers.” Do you identify a specific connection between the experience of having grown up always working through translation and then experiencing in Japan something that was beyond translation?

CWE: There are certain things – and we all experience these things – that happen in our lives that are very significant that are just triggers. I was ready for that to happen. Akiko Miyake and Nobu Nakamura at CCA Kitakyushu gave me my first opportunity to come to Japan. I feel in a strange way as if Japan was the place that was always – it was not that I found Japan, Japan found me in some sense. There was this mirrorical return, as it’s referred to in psychoanalysis, much as Marcel Duchamp says that you are not looking at the object, the object is looking at you. There was something deeply satisfying, strange and mysterious about this zone, this territory of non-understanding. I knew that it meant something, so what I had to do then was access my intuition, and that was the big trigger for me. That was the step I had to take in order to produce a body of work that could exploit that experience.

I’m working at the moment with scientists in the research institute at CERN in Switzerland, where they have the Large Hadron Collider. These scientists love to drink a bottle of wine and smoke cigarettes at lunchtime and it’s not at all like what you might imagine. It’s hard for me to comprehend what dark matter is, but I’m very interested to speak to people who also would not be able to really give you a straightforward answer. These people are extraordinary because they have to take enormous intuitive leaps in order to arrive at potential new forms of explaining the world. That certainly has to do with language because they need to find new forms of language, and that’s also what I feel my role is as an artist: the project is about new forms of language, new forms of comprehension, new forms of connectivity.

My first visit to Japan was in the 1990s. I was reading a lot at the time, not only Guy Debord but also Michel de Certeau and theories of urbanism and connectivity. I don’t think it’s some strange epiphany or religious experience, but what occurred to me upon visiting a megalopolis like Tokyo was that the matrix of the codes that the city was performing was devastating to me. It happened also in São Paulo and New York. It’s become abused for exceptional and very depressing reasons, but I want to reclaim the term “awesome.” There was awe involved.

Part III. Interview with a Cat

Hic et Nunc; or, The Delirium Beyond Translation