Claude Cahun

May 24 – September 25, 2011

Jeu de Paume, Paris

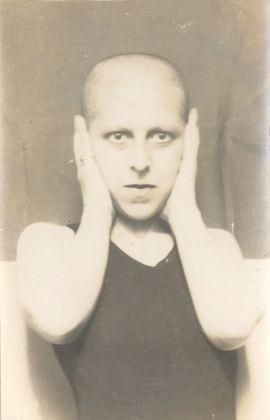

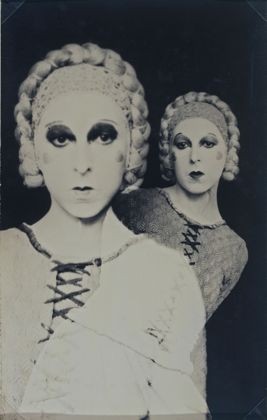

Left: Autoportrait (1928), 13.9 x 9cm. Jersey Heritage Collection, © Jersey Heritage. Right: Autoportrait (1929), 14 x 9cm. Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, © Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris / Parisienne de Photographie.

A Jewish, lesbian intellectual who collaborated with Bataille, Breton, Michaux and Tzara, lived through the German occupation of Jersey during World War II and was sentenced to death by the Nazis for resistance activities, Claude Cahun is an ideal candidate for the kind of retrospective exhibition that shakes up narratives of Modernity by introducing an under-recognized artist back into public consciousness. Indeed, the current exhibition at Jeu de Paume seemingly has this in mind, as it is the largest presentation of Cahun’s work in France in 16 years.

The exhibition focuses on black-and-white photographic self-portraits and Surrealist compositions from the 1920s and ’30s, as well as a few works from the post-war period (Born Lucy Renée Mathilde Schwob in 1894, Cahun survived her Nazi incarceration, dying a free woman in 1954). Cahun is best known for self-portraits that anticipate the work of contemporary artists like Cindy Sherman and Yasumasa Morimura. In these we see her alternately conjuring Alpine dairy girls, resplendent gurus, rosie-cheeked coquettes, gypsy mystics and dashing playboys – scenarios often set against stark backdrops and accentuated by ghostly double-exposure and mirror effects that suggest Cahun found in splitting her gender a way to double her self. Although her costuming has an undertone of Flapper hedonism, it is pushed beyond the realm of dilettantism by Cahun’s awareness of the relationship between lens and body, and her striking features (with her aquiline nose and severe profile, she evokes a cross between Tilda Swinton and David Bowie).

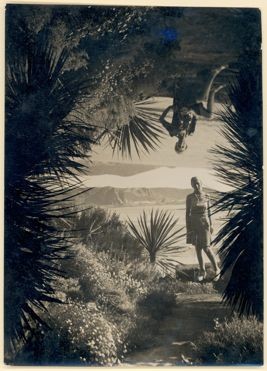

Left: Autoportrait (1939), 16 x 11 cm. Jersey Heritage Collection, © Jersey Heritage. Right: Combat de pierres (1931), 21 x 15.5 cm. Collection particulière, © Photo Béatrice Hatala.

Among later works, a self-portrait from 1939 finds Cahun standing in a lush garden path perched atop a promontory overlooking a bay; in this double exposure, the setting is flipped upon itself so that two images of Cahun find themselves head-to-head and enclosed by a funhouse organic architecture with columns of palm fronds framing a vista that explodes into an uncanny mirror horizon. However, Cahun’s doubles wear different clothing and strike different poses, the one standing and the other sitting; the backdrops themselves are revealed to be different sites in what can now only be assumed to be the same location; the identity of the image (its relations between negative and positive, self and projection) comes undone in the parallax of juxtaposition. Cahun exploited the intrinsic fiction of the camera, and her Surrealist compositions reinforce this sense, as with the print Combat de pierres (1931), in which outstretched arms superimposed over images of rocks suggest a pair of stony wrestlers, or in staged arrangements of disparate objects.

However, the exhibition suffers from an oddly claustrophobic layout of works installed one after the other along two narrow corridors and in a third room. The result is that one feels simultaneously overwhelmed and yet unsatisfied. With many photographs apparently destroyed by the Nazis after they ransacked her home in Jersey searching for evidence of resistance activity, Cahun’s oeuvre is necessarily fragmentary. The curators struggle with this out-of-contextness. In organizing the exhibition chronologically and filling it out with supporting material such as the informative but more or less conventional film Playing a Part: The Story of Claude Cahun (2005), they gloss over the discontinuities in the existing documentation when these could have been physically deployed in creating a better understanding of who Cahun now is, and what she has become in history. An artist who shifted so dramatically between feminine and masculine, self and other, Cahun proves an elusive figure to sum up. If this makes it unlikely that she will ever be institutionalized in a reformed canon of 20th-century art, this is hardly a failure. As she wrote to Breton a year before her death, “Legalism is an abomination. I loathe it…remain anarchic.”

The exhibition tours to La Virreina Centre de la Imatge, Barcelona, from October 27, 2011, to January 29, 2012; and the Art Institute of Chicago from February 25 to June 3, 2012.