A Restatement: The Art of ‘Ground Zero’ (Part 35)

Osamu Kokufu’s Engine in the Water and its other selves

Installation view of “Osamu Kokufu: Engine in the Water Redux” Part 2 (2017) at Art Space Niji. Photo: Tomas Svab.︎

Installation view of “Osamu Kokufu: Engine in the Water Redux” Part 2 (2017) at Art Space Niji. Photo: Tomas Svab.︎It was at the beginning of autumn last year that I heard from independent curator Mizuki Endo about the Osamu Kokufu Engine in the Water Recreation Project. I had only just brought to fruition Mokuma Kikuhata’s “Slave genealogy (with three logs) – remake” (1961-2016) at the Busan Biennale 2016, for which I served as a curator, so the recreation of artworks from the past was something with which I was not unfamiliar. These aside, artworks of historical important have been recreated in no small numbers over the years. One familiar to many people and can be viewed at a museum in Japan is Wounded Arm (1936), an important early work by Taro Okamoto that was actually recreated after the war (1949). So it is by no means rare, but the main problem in the case of this latest recreation project was that it was carried out in the absence of the artist. Because even if the work can be reproduced faithfully, the artist himself, who alone can determine the basis for judging whether the “recreation” is a success, has already passed away.

In 2014, soon after the opening of his solo exhibition “Floating Conservatory” at the Aomori Contemporary Art Centre, Kokufu collapsed and lost consciousness while making adjustments to his new work Endless Rain, still plagued by faults, after the museum had closed for the day. He was taken to an emergency hospital in Aomori but never regained consciousness. A light vehicle engine was still running inside the sealed space, and the cause of death was deemed to be acute carbon monoxide poisoning due to the inhalation of engine exhaust. The exhibition was hastily cancelled, and “Floating Conservatory” became in effect a show that never was.

Installation view of Osamu Kokufu: “Homage to Floating Conservatory” (2016) at Gallery A4.

Installation view of Osamu Kokufu: “Homage to Floating Conservatory” (2016) at Gallery A4.On the second anniversary of Kokufu’s death in the spring of 2016, an exhibition of Kokufu’s work entitled “Homage to Floating Conservatory” (Gallery A4, Takenaka Corporation Tokyo HQ) was staged by a group of volunteers, at which Floating Conservatory, the work that gave its title to the Aomori exhibition, was recreated. However, because the original work relied on the incorporation of the interaction and circulation between it and the form and site environment of the Aomori Contemporary Art Centre building and the surrounding vegetation as well as on the inversion of interior (exhibit) and exterior (nature) as they pertained to the venue, there was some debate as to whether its reproduction in the heart of a city in an environment that could be called the antithesis of that of the Aomori exhibition would really be in line with the wishes of the deceased artist. Which is precisely why this could only ever be an “homage” exhibition to Kokufu and not a Kokufu exhibition per se.

Similar difficulties remain unresolved with this latest project. In fact, they have been doubled. Firstly, reflecting the approach Kokufu adopted to making art throughout his career, hardly any of the parts of the original works remained, and moreover, even “reproducing” them, to say nothing of “recreating” them, is extremely difficult. This is a result of him incorporating natural ecosystems and the migration and circulation of elements within them that were important concepts confronting his artworks into completed mechanical operations and artmaking where such things would not normally not be present. For example, because Engine in the Water involved forcibly running an automobile engine (Subaru Sambar) inside an acrylic tank filled with water, the engine exceeded the limits of its durability with each exhibition, as a result of which none of the original engines survived. And because almost all of the work involving the running of the engines in water was done by Kokufu alone without the help of experts, neither did any manuals survive.

Thus there are numerous problems with this work from the point of view of not only the constituent parts but also purely the engineering. In fact, Kokufu himself was continually carrying out maintenance work (replacement of the water in the tank; deterioration, short circuiting and flooding of the self-starting motor, operation of the engine) while the work was on display on the two occasions in the past when it was exhibited (at Art Space Niji in 2012 and at the Nishinomiya Otani Memorial Museum in 2013). In the case of Endless Rain, the work that ended up taking his life, he rejected the idea of installing an exhaust pipe suggested by the organizers, probably for reasons to do with the work’s appearance. For this latest exhibition of Engine in the Water, however, to make absolutely sure, the minimum necessary equipment such as an air compressor to prevent flooding has been added here and there.

Installation view of “Osamu Kokufu: Engine in the Water Redux” Part 2 (2017) at Art Space Niji. Photo: Tomas Svab.︎

Installation view of “Osamu Kokufu: Engine in the Water Redux” Part 2 (2017) at Art Space Niji. Photo: Tomas Svab.︎Thus for this project – as Endo had raised as problems from the initial planning stage – the factors guaranteeing identicalness with the original work included not only the physical parts and aesthetic judgments, but everything from the engineering that required repeated trial and error throughout the exhibition period to the constant maintenance. If we regard these as a kind of performative physical intervention by the artist, then even if the organizers had succeeded in running an engine of the same type in water using as many of the parts that Kokufu used as possible, even though it would be “an engine made to run in water,” it would be extremely questionable whether or not it could be called Kokufu’s Engine in the Water. But there is another problem arising from a separate issue. Endless Rain, the work that ultimately claimed Kokufu’s life, was similarly realized on the basis of running an engine in a sealed space. It was in the course of the “constant maintenance” required to correct faults with this setup that the accident occurred. Though the degree of danger may be different, the possibility of such unforeseen accidents occurring also exists in the case of this work, which requires supplying gasoline and forcibly running an internal combustion engine in water. If something like an unfortunate accident were to occur this time, too, then it would mean those left behind had learned nothing from Kokufu’s death.

However, one could also say it was precisely on account of these problems that Endo launched this project. I will touch on this matter again later. But first and foremost, the fact is that Kokufu himself was more aware than anyone of the room for accidents with Engine in the Water. Because in the background of Engine in the Water, which when compared with the style of his previous works that stressed harmony with the environment and affinity with the human body is of a strikingly different bent, was the severe accident at TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant triggered by the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in 2011. Such was the shock of this event that apparently Kokufu was unable to produce any works for some time. In other words, for Kokufu Engine in the Water was also a response to his inability to make works in the way that he had until then – or, to enable him to continue making works after the disaster.

Because nuclear power generation emits a smaller amount of carbon dioxide into the environment than thermal power generation, it has long been intentionally touted as a clean, environmentally friendly power generation technology. However, nuclear power plants, which use enriched uranium as fuel and rely on the continuous generation of heat through nuclear fission, are essentially giant “water heaters” that generate power by turning turbines with steam produced by boiling water, and in this sense, while the technology behind them is reputed to be new, it is in fact a product of the industrial revolution that has remained unchanged since the 19th century. Automobile engines are internal combustion engines, which cause pistons to move by combining gasoline and oxygen inside sealed cylinders and causing them to ignite explosively, and the exhaust gases generated in this process pollute the global environment terribly. While in this respect the two are in contrast with each other, they are both energy sources that originate in the 19th century. From early on in his career, Kokufu actively incorporated into his work solar panels, an example of 20th-century technology and therefore fundamentally different from these 19th-century technologies, so if he found his own identity as an artist in this there would have been no need for him to be so shocked at the Fukushima nuclear accident. Why, then, in spite of the very real risk of an accident occurring, did he go to the trouble of producing works like Engine in the Water and Endless Rain after the accident, continuing to focus if anything more strongly on the negative elements of the internal combustion engine?

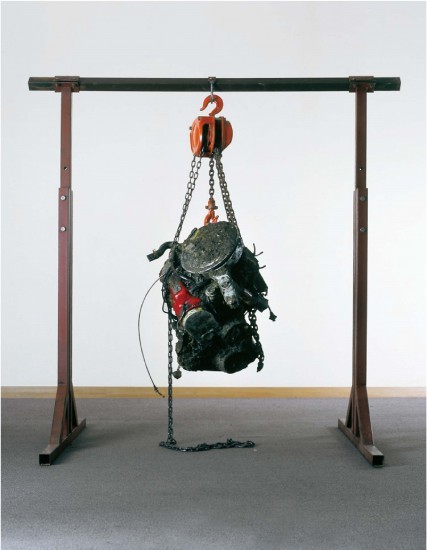

At “Osamu Kokufu: Engine in the Water Redux” (July 2017, Art Space Niji, Kyoto), which was planned as the second installment of the series that began with the group exhibition “Singing in Falsetto” (April-June 2017, Oyama City Kurumaya Museum of Art, Tochigi), which Endo himself curated and which marked this project’s debut, Endo is providing a fresh opportunity to think about this. (The Art Space Niji show is the third “game” in what Endo calls the “Japan Series,” with the Oyama City Kurumaya Museum of Art show counting as the second.) Incidentally, the contents of Part 1 and Part 2 of the exhibition at Art Space Niji, which is also the venue where Engine in the Water was first unveiled (and therefore serves as a repeated starting point), are substantially different, and at the time of writing this review I had not seen Part 2. In Part 2, a newly prepared engine (No. 4, with Endo naming retrospectively the engine used at “Singing in Falsetto” No. 3 and those used by Kokufu himself Nos. 1 and 2 in a manner that clearly calls to mind the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant reactors) will be introduced and operated. As for Part 1, the No. 3 engine whose role came to an end with the “Singing in Falsetto” exhibition was hauled out of the water and cruelly and somewhat violently hung in midair.

Installation view of “Osamu Kokufu: Engine in the Water Redux” Part 1 (2017) at Art Space Niji. Photo: Tomas Svab.︎

Installation view of “Osamu Kokufu: Engine in the Water Redux” Part 1 (2017) at Art Space Niji. Photo: Tomas Svab.︎In doing this the organizers were referencing the exhibition of an earlier work by Kokufu entitled Time in the Ground (1993-2007), unveiled in 2007 before Engine in the Water. But why Time in the Ground? In 1993, Kokufu came up with the idea of burying an engine in his backyard. It is not clear whether he thought of it as an artwork at this time, but fourteen years later in 2007 he dug up this engine and hung it up (or rather exposed it) as a lump of metal (junk) that had ended its function as an internal combustion engine, calling it Time in the Ground. Even supposing that the making of Engine in the Water had been prompted by the Fukushima nuclear accident, Time in the Ground was unveiled to the world four years earlier and in accordance with Kokufu’s own decision was referred to in the publicity material at the time of the unveiling of Engine in the Water. There are similarities between these two works in that both involve burying (one “in the ground” and the other “in the water”) engines that in both cases exceed the limits of their durability and end up as junk on each occasion. In other words, the concept that serves as the prototype for Engine in the Water is not reliant on the Fukushima nuclear accident but was latent within Kokufu.

Osamu Kokufu – Time in the Ground (1993-2007).︎

Osamu Kokufu – Time in the Ground (1993-2007).︎With this in mind, at Part 1 of the “redux” exhibition, Endo hauled up an engine of the same kind that had finished its role at “Singing in Falsetto,” though it was not from the ground but from water, and presented it hanging in the same manner as Time in the Ground. This is no longer a recreation or reproduction of Engine in the Water. Of course, it is different, too, from a recreation or reproduction of Time in the Ground. What, then, is it? Endo calls this exhibit Work Material “Engine No. 3”, with no reference to Kokufu’s name or even to the story behind Engine in the Water. If anything, the main exhibits at Part 1 of the “redux” exhibition are in fact the documentary videos showing engine No. 1 on display at Art Gallery Niji in 2012, engine No. 2 on display at the Nishinomiya Otani Memorial Museum in 2013, and Engine No. 3 on display at the Oyama City Kurumaya Museum of Art in the spring of this year (incidentally, these videos were provided for the purposes of this exhibition by the owners at the request of the organizers, with the original monitors located and used as is where possible). In Part 2, documentary video of Engine No. 4 on display will no doubt be added to these.

In this way, the Engine in the Water Recreation Project is only realized in the context of the project itself being constantly reorganized, its direction being adjusted and its meaning being questioned anew while it is underway. It would not be overstating things to say that, based on a variety of circumstances, there is already a pressing need for the title of the project itself to be fundamentally altered. However, it would be wrong to treat this as a shortcoming of the project. Rather, surely the “triggering of discussion” arising from such questioning and reframing is itself the substance of this “project without substance” that seeks to recreate (hence “redux”) Engine in the Water, which was itself “incomplete” and left room for this. In this sense there is a clear distinction between this project and earlier, more conventional, “recreations.”

Osamu Kokufu (1970-2014).︎ Photo: Tomas Svab.︎

Osamu Kokufu (1970-2014).︎ Photo: Tomas Svab.︎However, it would have to be said that for precisely this reason, the core of this project cannot be limited solely to the question of how in the wake of his death we should perceive the artworks Kokufu left uncompleted (to be exact, we do not even know for certain whether they are complete or not). Rather, it extends to the broader questions of how we should deal with, pass on and assess existing artworks after the death of the artist. Because today, art is increasingly focusing away from tangible, stand-alone items such as paintings and sculptures in favor of the reorganization of relationships in a project format, and it is clear that we will soon run into serious problems concerning how best to retain these works going forward. The most sensible solution that immediately comes to mind is probably that instructions prepared by the artist and documentation concerning the work, ie, material ranging from video to photographs, be treated as the equivalent of artworks and stored at art museums. But this can only come about as a result of the topsy-turvydom of methods that were originally adopted for the purposes of critiquing stand-alone artworks in the context of various relationships ultimately being kept in storage rooms as tangible things. And while I think it is fine for this to happen, it is as clear that this kind of conservation that views relationships as tangible things does not extend to the limits of the durability of paintings and sculptures whose fundamental appeal is as stand-alone items. Though they may certainly be stored away, I very much doubt they will be able to actively “induce discussion” into the future. A symposium provisionally titled “The Future of the Present of the Past 2(1) is scheduled to be held at the museum in November, so I look forward to a more detailed discussion of this and related questions as they pertain to Engine in the Water then, but in the meantime we should perhaps regard the core in the true sense of the term of Endo’s Engine in the Water Recreation Project as being directed at these kinds of long-range issues that extend into the future.

By a strange twist of fate, on the day I visited the exhibition venue, Kyoto was hit by a sudden torrential downpour. I was forced to stay indoors at the nearby National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, where I had stopped before heading to Art Space Niji and where in the Collection Gallery “Curatorial Studies 12: The 100th Anniversary of Duchamp’s Fountain” happened to be under way. This is a series of five exhibitions organized to mark 100 years since Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain entered the annals of 20th century art in 1917, each put together by a different curator (my visit coincided with the fifth exhibition in the series, “He CHOSE it.,” curated by Yukio Fujimoto) and each reconsidering Duchamp’s Fountain from the standpoint of a completely different display concept.

In a way, it made sense that immediately prior to heading to “Engine in the Water redux” I was unexpectedly detained at this exhibition centered on Duchamp’s Fountain due to a seemingly endless sudden downpour (endless rain?). Because in both cases the artist is dead and the original version of the work no longer exists, with only photographs and replicas remaining (at the risk of overstating things, both also concern water, even down to Endo’s given name, which includes the Chinese character for “water”), yet despite this Duchamp’s Fountain has survived all of 100 years like an inexhaustible spring and continues to vigorously induce discussion among those that remain. More than a few experts are of the view that contemporary art itself was born out of this work. But what, then, is its “secret”? If one thing is certain, it is not because it was kept in storage at a museum. Because the original does not exist. So what is it? In fact, through Engine in the Water, it is precisely this that we need to think about.

“Osamu Kokufu: Engine in the Water Redux” Part 1 was held from July 4 to 16, and Part 2 from July 18 to 30, 2017, at Art Space Niji. Kyoto.

- This project is scheduled to be part of a symposium provisionally titled “The Future of the Present of the Past 2” to be held on November 23, 2017 at the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art. The symposium overall will consider the possibilities of the art museum system and archives in relation to the recreation and conservation of contemporary art.