A Restatement: The Art of ‘Ground Zero’ (Part 36)

‘Tower of the Sun’ and ‘Great Peace Prayer Tower’

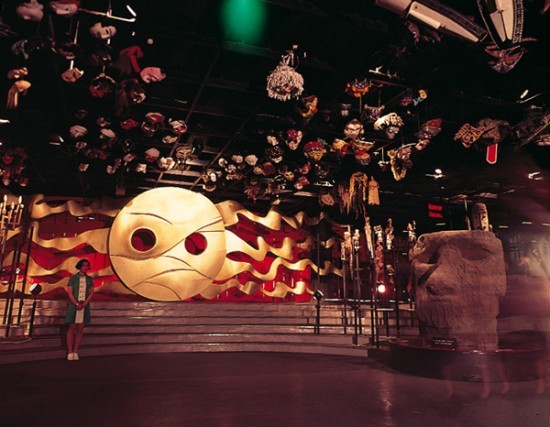

Okamoto Taro – Sun of the Underworld (1970). Photo courtesy Expo ’70 Commemorative Park Office.︎

Okamoto Taro – Sun of the Underworld (1970). Photo courtesy Expo ’70 Commemorative Park Office.︎At the Expo ’70 Commemorative Park in Osaka’s Senri Hills, repair and renovation work is currently underway on the interior of the Tower of the Sun. Restoration work on the Tree of Life, which has not been displayed in public for many years; reconstruction of the Sun of the Underworld, the tower’s missing fourth face; and preparation of the installation sites for these works in readiness for the opening of the tower’s interior in March 2018 are all proceeding at a fever pitch as part of the Tower of the Sun Interior Restoration Project. The other day, in my role as a trustee of the Taro Okamoto Foundation, I was granted access to the tower’s interior together with Taro Okamoto Memorial Museum director Akiomi Hirano, art historian Yuji Yamashita and Watari Museum of Contemporary Art curator Koichi Watari to see how things were progressing. Inside, the seismic strengthening had already been completed and work on a new passageway to enable viewing of the Tree of Life was underway. The space that was once open like a Buddhist temple hall was filled top to bottom with scaffolding resembling a series of complex puzzles, giving it the appearance of a steel cobweb. This complex arrangement of scaffolding was apparently the result of advanced mathematical computer-based processing. But despite this, the subdued primary colors of the Tree of Life, whose face was visible through the gaps in the scaffolding, and the surviving models of creatures were the same as when the Expo was held, as if time had stood still. And when I reminded myself that we were inside the once ruinous Tower of the Sun, I was suddenly struck by how incredible the whole thing was.

I first entered the Tower of the Sun to view the Tree of Life back in 2000, 30 years after Osaka Expo ’70. I was able to do this through the introduction of the late Toshiko Okamoto as part of an effort to study and record conditions inside the tower. However, given that virtually no work had been done on the interior for several decades, it was the epitome of a ruin. As I have written about this previously (Black Sun and Red Crab – Taro Okamoto’s Japan, War and the World’s Fair), I will not go into the details again here. Suffice to say, though it is not very widely known these days, the Tower of the Sun was originally not a freestanding structure. It was part of the Theme Pavilion, whose main exhibition spaces were located on the basement and mid-air levels. It also functioned as a thoroughfare enabling people to move between these two levels via escalators.

Tree of Life. Photo courtesy Expo ’70 Commemorative Park Office.︎

Tree of Life. Photo courtesy Expo ’70 Commemorative Park Office.︎Unfortunately, it is no longer feasible to restore the exhibits in the basement level, now filled in, and in the demolished mid-air level. However, in the basement level was the roughly 11-meter-wide fourth face, which was closely connected to the Tower of the Sun. Even if restoration of the basement exhibits was impossible, surely something could be done about the Sun of the Underworld, the original of which went missing and has never been found. It was in response to such strong feelings that it was decided that, with the cooperation of Kaiyodo, a toy manufacturer known for its capsule toys and other fine figurines, this fourth face would be reproduced in its original size. A model (scale 1/10 = w1.1m) was built and can be viewed on the Expo ’70 Commemorative Park website. Recently, however, a full-scale replica was completed, so I also visited the model-maker’s shop in Kyoto to inspect it.

Scale model for the reproduction of the Sun of the Underworld. Photo courtesy Expo ’70 Commemorative Park Office.︎

Scale model for the reproduction of the Sun of the Underworld. Photo courtesy Expo ’70 Commemorative Park Office.︎The fact is, not only the actual Sun of the Underworld, but the original plans, too, are missing. Accordingly, in recreating it, the only option was to generate a three-dimensional form and reconstruct the entire thing based on multiple photographs taken at the time from various angles. It became all the more important, then, to capture the “essence of Taro Okamoto.” Our main job was to give our initial impressions of the result. However, leaving aside a few details that needed amending, it would be fair to say there were no major discrepancies whatsoever. In fact, as a result of being able to view the Sun of the Underworld, at its original scale, albeit in the form of a model, after having only ever seen it in photographs, I discovered many new things. For example, that the flames extending to the left and right represent both flames and the “fluttering” of ribbons, something Taro had often used as a motif since his Paris days. Also, that this fluttering movement generates a dynamism that not only extends left and right but traverses the face horizontally. But further discussion of this is perhaps best left for another occasion.

Be that as it may, what incredible sculpting! Standing once again directly under the Tower of the Sun, I was reminded of how extraordinary it is. At the same time, I found myself thinking about another tower with an extraordinary shape that stands directly south of Senri Hills in Tondabayashi. I am referring to the Non-Denominational Great Peace Prayer Tower for War Victims of All Nations (hereinafter the Great Peace Prayer Tower) built by the Church of Perfect Liberty (PL). After learning that this other tower – which in part because it is a religious facility, I had only viewed from a distance to that point – was completed in 1970, and therefore the same age as the Tower of the Sun, I sensed some kind of sign and decided to take the opportunity to visit it.

Great Peace Prayer Tower. Photo courtesy PIXTA.︎

Great Peace Prayer Tower. Photo courtesy PIXTA.︎In fact, this tower is far larger than the Tower of the Sun. Whereas the Tower of the Sun is around 70 meters tall, the Great Peace Prayer Tower is around 180 meters. But the main thing the two have in common is that, while they have the word “tower” in their titles, both the Tower of the Sun and the Great Peace Prayer Tower are actually “works of art.”

The Great Peace Prayer Tower was completed on August 1, 1970, five months after the opening of Osaka Expo ’70 in March the same year. Its stated purpose is as a place to honor the memory of the victims of all wars since the dawn of history and to pray for the realization as soon as possible of everlasting world peace. However, its concept goes back far earlier than that of the Tower of the Sun. In fact, the very surrounds of the Great Peace Prayer Tower, which stands on a large site, are a “sculpture garden” that is home to a total of thirteen sculptural works by twelve sculptors from Japan and overseas. The artists were all leading exponents of modern sculpture in the 20th century (including Shin Hongo and Bushiro Mohri from Japan and Herbert Baumann and Morice Lipsi from overseas), making for an impressive lineup.

The circumstances surrounding the creation of the works installed around the Great Peace Prayer Tower can be traced back to the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. On the eve of this event in 1963, the International Symposium of Modern Sculpture (sponsor: Asahi Shimbun Company; chairman: Soichi Tominaga) was held in Michinashi on Izu’s Manazuru Peninsula, attracting sculptors from around the world. Due to the fact that the venue was located on an area of coastline known for its production of Komatsu Ishi, a high-quality stone formed by the cooling and hardening of lava emitted during volcanic activity in Hakone, a competition involving the production of artworks using this stone was held. Later that year the completed artworks were transported to Tokyo where, after being displayed for a short time outdoors in the Shinjuku Imperial Gardens, they were installed in a garden near the Yoyogi National Gymnasium for the duration of the Olympics the following year. Designed by Kenzo Tange, who served as overall producer of the Symbol Zone at Expo ’70, the Yoyogi National Gymnasium contains a mural by Taro Okamoto. Tange was also a member of the executive committee for the sculpture symposium in Manazuru, and in this sense, too, one could say that these sculptures and Expo ’70 very nearly crossed paths. The exact circumstances behind their ending up in the possession of PL are not known.

However, as hinted at above when I wrote that the Great Peace Prayer Tower itself should be regarded as a work of art, the first of PL’s “21 Precepts” (and there is something about this that calls to mind Taro Okamoto) reads: “Life is art.” This teaching is the work of the church’s Second Patriarch, Tokuchika Miki, suggesting that the relationship between art and the church is extremely close. In fact, the model for the Great Peace Prayer Tower was formed out of clay by the Second Patriarch himself. In this sense it is indeed a “work of art,” but there is another, earlier work on which this model was based. I am referring to the Tower of Life, a commissioned work created for PL by Sofu Teshigahara, who was closely connected to the church. According to the church member who accompanied me during my visit, the Second Patriarch got the idea for the Great Peace Prayer Tower and commissioned Teshigahara to come up with a model after the International Symposium of Modern Sculpture, which means that this project would have started immediately after the Tokyo Olympics. The reason Teshigahara’s model was not used as is was apparently because the form, which was based on a piece of driftwood, was not suitable for a massive structure. Consequently, the Second Patriarch came up with an alternative design based on Teshigahara’s model.

Although it did not come to fruition as the Great Peace Prayer Tower, Teshigahara’s Tower of Life (the title is almost as if the Tower of the Sun and the Tree of Life had been combined, is it not?) is today still displayed as an outdoor sculpture in a corner of PL’s headquarters. On that subject, in terms of both its color and its form, the PL shrine I saw during my tour of the tower on the day of my visit (lower second level, Great Peace Prayer Tower) is somewhat reminiscent of Taro Okamoto’s Tree of Life. Is this really an accidental coincidence?

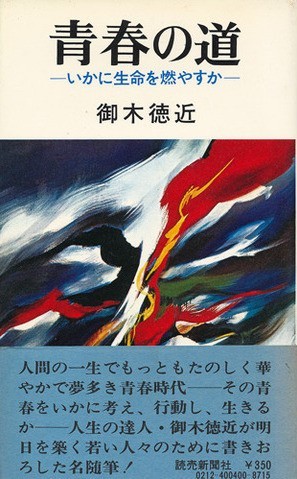

Yoshio Ko, who also goes by the name of the “international dark producer,” is known to have had dealings with PL’s Second Patriarch, but in a discussion titled “Kami o yobu otoko” (The man who summons the gods) published in the magazine FUKUJIN (No. 11, 2006, Byakuya-Shobo), it was revealed that not only Teshigahara but Taro, too, had dealings with PL’s Second Patriarch at around the same time. In fact, Taro contributed a drawing for the cover of Tokuchika Miki’s book Seishun no michi: ika ni seimei o moyasu ka (The way of youth: how to light up life), which was published in 1971 by Yomiuri Shimbun.

Tokuchika Miki, Seishun no michi: ika ni seimei o moyasu ka (The way of youth: how to light up life) (Tokyo: Yomiuri Shimbun, 1971).︎

Tokuchika Miki, Seishun no michi: ika ni seimei o moyasu ka (The way of youth: how to light up life) (Tokyo: Yomiuri Shimbun, 1971).︎Come to think of it, PL is known for one of Japan’s largest fireworks displays. Naturally, given that “art” is mentioned in the first of the church’s precepts, this display is referred to as “PL Art of Fireworks.” Apparently this also originated with the Second Patriarch. If fireworks are art, then surely one could also say (as Taro did) that “art is an explosion.” As to exactly what kinds of dealings there were between the two men, at this stage I cannot say. But it is a matter I would like to continue to look into.