A Restatement: The Art of ‘Ground Zero’ (Part 3)

Iwaki Yumoto I

Exterior view of the Mihako-za

Exterior view of the Mihako-za After taking part in the symposium Community and Art in the Aftermath of March 11: Before and After, held October 30 of last year at the Hotel Kanyo in Minami Sanriku, Miyagi Prefecture,(1) a group of us visited the bustling Fukko-ichi market set up by locals to support the town’s reconstruction. I was on my way back when I was stopped by some people involved in the Mihako-za Rebirth Project who had traveled from Iwaki Yumoto Onsen in Fukushima Prefecture. Mihako-za is the name of an old theatre in the part of Yumoto where the hot spring inns are clustered. It was once used by locals as a venue for independent theatre productions, meetings and screening movies among other things. The Mihako-za Rebirth Project was launched by a group of volunteers who came up with the idea of using the building, which had long been abandoned, to help revitalize the local community through art.

The project seemed to be going smoothly, until 2:46 pm on March 11 – that is, when the community was among those struck by the massive earthquake. To make matters worse, there followed a series of explosions at TEPCO’s Fukishima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant and the large-scale release and dissemination of radiation. Iwaki Yumoto Onsen is around 45 kilometers from the Fukishima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, and even closer to the Daini Nuclear Power Plant. On the government’s advice, the residents quickly took refuge indoors. It is not difficult to imagine the extent to which excruciating anxiety and confusion spread.

In what might best be called a bright spot in a tragedy, the area around Yumoto escaped serious contamination due to the fickleness of the wind direction. However, micro-hotspots remained here and there, meaning that children were unable to swim in the ocean or even in pools over the summer. Tourists disappeared from the normally busy shopping streets in the part of the town where the hot spring inns are clustered, which instead became an accommodation center for the workers carrying out repairs at the Fukishima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. As for Mihako-za, although the building itself is structurally sound, the shaking caused minor damage in places and understandably there was confusion in the immediate aftermath of the disaster, as a result of which it naturally became difficult to continue with the project.

After hearing about the symposium at Minami Sanriku, the people involved in this project expressed interest in hosting a similar discussion in Yumoto about the future of art in their community. In response, I decided to bring my schedule forward and found time before the end of the year to visit Yumoto Onsen. Over the preceding six months I had visited various sites affected by the tsunami, but this would be my first visit to Fukushima Prefecture since the disaster.

On December 3, I set off for Yumoto from Ueno aboard the Super Hitachi limited express on the Joban line. It was pouring with rain when I arrived. I went straight to my hotel, where workers from the nuclear power plant had been staying. Now that cheap lodging facilities have been constructed the workers are not as numerous as before, but I did see a number of people in work clothes during my stay. After taking a look at the Mihako-za, which despite being just a short distance away has fallen into a state of disrepair, several dozen of us gathered in a circle in a large room back at the hotel where the symposium got underway. Or perhaps “gathering” is a better word to describe it. It was an unpretentious, self-staged event. However, in the present circumstances, I felt this was entirely appropriate. Ultimately, one cannot prepare answers in advance to the problem at hand. All one can do is talk heart-to-heart and discuss it together.

The theme for the symposium was, Thinking about Negative Expression: How Do We Depict Radiation Here? As well as myself, the panel included Sumiko Kumakura from Tokyo University of the Arts, artist Hiroshi Fuji, and from Okinawa Ryoji Hayashi, co-representative of Studio Kaiho-ku. We took turns speaking, and before we knew it we had exceeded the scheduled two hours. As for the contents, no doubt there will be opportunities to touch on that elsewhere. What I want to stress here is that during my visit to Iwaki Yumoto I was taught so much more than I was able to offer in the way of advice. It was I who was given the opportunity to learn.

Of the things I learnt, the most surprising was that Iwaki was one of Japan’s foremost coalmining areas in the modern era and the main source of energy for Tokyo and adjacent prefectures during and after World War II. Previously, whenever coalmining was mentioned I would immediately think of Tagawa in Kyushu or Yubari in Hokkaido, but never Iwaki. I seem to have forgotten completely that the energy resources that powered the industrial infrastructure in the region where I was born and raised – including the thermal power of the Keihin Industrial Zone – came from Iwaki. Why had I forgotten this history? One could always attribute it to insufficient study, but as I walked around this area and saw it with my own eyes, I began to think there might be another reason.

After sitting face-to-face with participants at the symposium and listening to their stories, the next day I was shown around some of the old coalmining sites that still remain here and there in the district, and in the course of this it struck me that the very Joban Line along which I had traveled to get to Iwaki was originally an “energy line” built to transport coal from the countryside to the metropolis. Now that I thought of it, along the route from Iwaki to Ueno there were large-scale thermal power plants, industrial towns such as Hitachi, towns such as Toride that thrived as bedroom communities serving these industrial towns, and of course Tokaimura, the site of Japan’s first nuclear power plant. And further along the Joban Line, in the Hamadori region of Fukushima facing the Pacific Ocean, are the Fukushima Daiichi and Daini nuclear power plants. Why, though, given that they are located in the Tohoku region, are these two nuclear power plants operated by the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) and not the Tohoku Electric Power Company? The reason is probably not unrelated to these historical circumstances. It is certainly not a recent development. Throughout the modern era, this region has been a supplier of electricity to Tokyo. What I had forgotten was the “throughout” part of the equation, which is what made me suspicious of my own memory lapse.

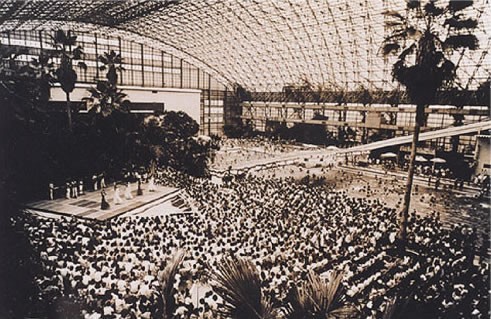

Interior view of the Joban Hawaiian Center

Interior view of the Joban Hawaiian Center Spa Resort Hawaiians (I still tend to use the old name, the Joban Hawaiian Center), the famous hot springs resort and amusement park not far inland from Iwaki Yumoto Onsen, was built as a major center for the local tourist industry, which became an alternative source of jobs as coalmines throughout the region were forced to close in the wake of the decline of Japan’s coalmining industry, falling victim to trade liberalization (events depicted in detail in the 2006 movie Hula Girls). The shift from supplying energy to tourism was a major one, but in fact both industries rely on the same infrastructure. To get to the resort, group travelers from Tokyo and adjacent prefectures use the old “energy line” in the form of the Joban Line or the Joban Expressway. Whether it be mining or generating electricity or even amusement, since the modern era this area has taken a tortuous course in continuing to serve the greater Tokyo metropolitan area, although at some point this has been forgotten by those who live in the capital.

At one point we climbed a hill overlooking Spa Resort Hawaiians from where we had a clear view all the way to the Pacific Ocean. The weather was perfectly fine, a stark contrast to the day I arrived, with a strong, dry wind blowing from the direction of the hills behind us. In an instant the reading on my dosimeter jumped to 0.78 microsieverts an hour (I was carrying a DoseRAE 2 electronic personal radiation detector). In Iwaki itself I obtained a reading of 0.19 microsieverts an hour in the rain, suggesting that the nearby hills are far more contaminated than the town. Peering out the car window at the winding mountain trails, I was again made painfully aware of the huge task that lies ahead in decontaminating the vast wooded areas around Iwaki. Everything about the scenery looks calm and peaceful, yet below the surface radioactive material is destroying it moment by moment.

Nearby was the area where workers who mined the coal lived communally. It had the air of a tranquil village, but according to my guide, who was involved in the mining industry at the time, it is an area full of dark memories. Just how many people died regrettable deaths due to explosions, fires, cave-ins and other accidents in this unforgiving work environment? In fact, no one knows the exact number. Those who tried to escape were mercilessly rounded up and brought back, and rent and even money for meals were deducted from wages, so that workers lived in a condition that was virtually between life and death. As I looked around a cemetery – littered with stones – where people who died leaving no one to tend to their graves were buried, I tried to imagine what it must have been like. Clutching what little money they had managed to earn, the miners ventured into the part of Yumoto where the hot spring facilities were clustered, letting off steam in what must have been one of the few pleasures available to them. The above-mentioned Mihako-za had a reputation as a place with a difficult-to-approach atmosphere where these “roughnecks” gathered. Undoubtedly, Mihako-za is more than just a cultural heritage site, pervaded as it is by a peculiar, almost brazen air. Things like the impact of the extra-bold lettering on the signboard are testimony to this.

As I was leaving my accommodation in Yumoto, a middle-aged housekeeper said to me in a strangely courteous manner, “Have a safe trip.” I was heading to the coastal area worst affected by the tsunami, and so had on sturdy boots and a down jacket with a hood and carried a black rucksack and a yellow Geiger counter. The housekeeper probably mistook me for a workman heading off to the nuclear power plant. I was taken aback – the reason being I had gained an insight into how every morning such women send off those about to undertake work that inevitably exposes them to radiation, leaving me with extremely mixed feelings. (To be continued)

- Symposium members: Yasuo Kobayashi (moderator), Yoshiaki Kaihatsu, Fram Kitagawa, Noi Sawaragi, Yumi Yoshikawa, Mitsuhiro Yoshimura. Sponsored by the Fukutake Foundation for the Promotion of Regional Culture.