A Restatement: The Art of ‘Ground Zero’ (Part 16)

Kota Takeuchi and Fukushima I: The demolition and rebirth of Mihako Theater

Kota Takeuchi – Demolition of Mihako Theater (2013), two-channel video projection, movie screen, camera, benches.

Kota Takeuchi – Demolition of Mihako Theater (2013), two-channel video projection, movie screen, camera, benches. Late last year I went along to Kota Takeuchi’s exhibition “Light Consuming Shadow,” which was on at the Mori Art Museum until December 23. Except it wasn’t the Mori Art Museum on the top floor of that high-rise building overlooking Tokyo’s Roppongi district. It was in Iwaki city in Fukushima prefecture, although the closest station is in fact Hisanohama on the Joban Line. It’s located beside a farm road that’s part of a network of roads extending from the area inundated during the tsunami in 2011 towards the mountains. It’s a private art museum housed in a wooden building painted completely black on the outside. If you didn’t know about it you certainly wouldn’t imagine it was an art museum.

Iwaki’s Mori Art Museum opened in 1995. The owner is Hideo Mori, an interior designer and former professor at Musashino Art University who was born in Fukushima prefecture. The building was designed by Hiroshi Ito. Having opened in 1995, it predates the Mori Art Museum in Roppongi by quite a few years, though in the aftermath of the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami the shows that had been scheduled at the time were cancelled (it did serve as the venue for a number of concerts), and this solo show by Kota Takeuchi, “Sight Consuming Shadow,” was in fact the first exhibition to be mounted there for a long time.

Incidentally, Iwaki city is an extremely large administrative division. Yumoto, which I have visited frequently since the disaster, has been a popular hot spring town since long ago and also once boasted a bustling entertainment area frequented by workers from the Joban Coal Mine Co., Ltd. Following the decline of the coalmining industry it was known as a rustic hot spring, but in the wake of the disaster it became an accommodation base for laborers recruited to work at the site of the nuclear accident at Fukushima, which is located in the same region of Hamadori, resulting in a noticeable decline in the number of tourists. In fact, though, while Yumoto is not far from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, the amount of radioactive material that settled on the ground was far less than the amount that settled in neighboring Nakadori, the “backbone” of the prefecture where both Fukushima city and Koriyama city are situated. Radiation dosages in Yumoto are also not all that different from the downtown area of Tokyo. But when you leave the township and head into the hills a short distance, the dosages suddenly increase. The area around the Mori Art Museum, too, is much more highly contaminated than Yumoto, and I heard that immediately prior to the exhibition closing the top soil in the surrounding area was removed, placed in flexible container bags and piled up near the museum entrance as part of the decontamination process. Usually a bright place with plenty of natural light, I arrived to find the museum plunged into darkness as a result of all the windows having been covered with black curtains. The ceiling is high, however, and with multiple works arranged so as to take full advantage of the space’s role as a combined museum and studio, the exhibition resembled a mini retrospective looking back on Kota Takeuchi’s activities over the last few years.

Kota Takeuchi – Demolition of Mihako Theater (2013), two-channel video projection, movie screen, camera, benches.

Kota Takeuchi – Demolition of Mihako Theater (2013), two-channel video projection, movie screen, camera, benches. Central to the exhibition is the new video installation Demolition of Mihako Theater (2013). It is a large work taking up a large part of the venue. Benches are arranged in a space separated from the other works by a partition on which visitors sit and quietly view a video projected onto a screen in front of them. In other words, this work recreates the space inside a movie theater – not just any movie theater, but the Mihako Theater that once actually stood in Yumoto’s entertainment district. I say “once,” because the Mihako Theater has been demolished and no longer exists (demolition work was completed in early June 2013). The screen and benches used in this work, however, are all original items obtained from the real Mihako Theater. Likewise, the video projected onto the screen is an edited version of footage shot from beginning to end of the week-long demolition of the Mihako Theater. And so the audience sits inside a theater recreated in the form of an installation inside an art museum and is taken back in time to witness the very theater in question being demolished.

The original Mihako Theater.

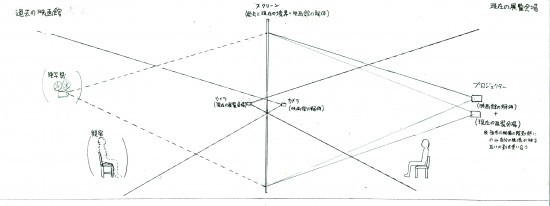

The original Mihako Theater. So, this is more than a simple “re-creation.” The footage recorded by Takeuchi also serves as a fixed point observation of the entire demolition process, with the camera set up where the Mihako Theater’s screen was once located. Accordingly, the line of sight along which the audience “views” the screen from the benches in the recreated Mihako Theater intersects the line of sight along which the screen in the actual Mihako Theater was once “viewed.” As well, because this intersection of past and present lines of sight is concentrated on a single screen, by setting up a live-streaming camera by the screen in the exhibition venue, Takeuchi is able to simultaneously (although in reality a slight delay occurs) “capture” in real time the “viewed audience” and “project” these images onto the same surface (ie, the screen). And so, while viewing from the benches on which they sit in the here and now footage of the already demolished Mihako Theater, viewers at the same time see footage of themselves looking back at them (ie, being looked at) from the actual screen of the no longer existing Mihako Theater.

Kota Takeuchi – Drawing for the Demolition of Mihako Theater (2013), water-based marker on paper, 21 x 29.7 cm.

Kota Takeuchi – Drawing for the Demolition of Mihako Theater (2013), water-based marker on paper, 21 x 29.7 cm. But why the Mihako Theater? Earlier I wrote that this exhibition serves as a kind of a retrospective of Kota Takeuchi’s activities over recent years. Its impetus can be traced back to the disaster of 2011. Takeuchi, who in the wake of the nuclear accident at Fukushima was involved in the recovery work as a nuclear power plant worker, spent twenty minutes pointing at a live-streaming camera set up at the accident site wearing protective clothing. He did this while monitoring on the screen on his mobile phone his own movements that were being captured by the camera in question and broadcast over the Internet. Yes, he was the so-called “finger-pointing worker.” This action, which he carried out anonymously, caused a stir on the Internet, though when a person claiming to be the worker responsible later explained the action by referring to Vito Acconci’s Centers (1971), the situation immediately assumed an artistic aspect.

Having taken an interest in this action, I followed multiple connections that convinced me that this person was the artist Kota Takeuchi. I requested an interview with Takeuchi through the art journal Bijutsu Techo. Throughout our discussions over several hours, however, not once did Takeuchi acknowledge that he was the finger-pointing worker. In the end, I took the unusual step of reviewing the actions of the finger-pointing worker as part of the “art practice” of Kota Takeuchi without determining that the two were actually the same person, which is to say without establishing “a correspondence between artist and artwork.”

Having thus established a relationship with Takeuchi – though having said that, to this day he has never publicly acknowledged that he is the finger-pointing worker, a fact that has remained an “open secret” (the title of the show where he first unveiled the finger-pointing worker piece) – in 2012, the year after the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami and following this series of events, I took the rostrum at a symposium in Minamisanriku, one of the towns affected by the tsunami, as a result of which I got to know the organizers of the Mihako-za Rebirth Project who had travelled from Iwaki Yumoto Onsen. In the winter of that same year I was invited to take part in a symposium dealing with issues surrounding the nuclear accident and expression, which led to me visiting Yumoto for the first time. In the course of the conversations we had at that time and my ongoing correspondence with people on the ground following my return to Tokyo, I came to think that the project to bring about the “rebirth” of the Mihako Theater, which had not only lost the building that served as its base after it was partially destroyed in the earthquake and tsunami but had also lost its very direction in the aftermath of the nuclear accident, would benefit in no small way if Takeuchi became involved, and so I brought the two parties together. As a result of this, Takeuchi became acutely aware of the fact that Yumoto, where he had previously resided as a nuclear plant worker, was once a focal point of the country’s pre-nuclear power energy industry as a coal-mining center, and driven by the desire to learn all he could about the industrial relics that remained in the area and about its unknown history, he eventually moved to Yumoto.

So in Demolition of Mihako Theater, the reversibility of the relationship between “the side pointing and the side being pointed at,” or “the person watching and the person being watched,” a reversibility Takeuchi first demonstrated when he “reversed” the live-streaming camera at the nuclear accident site by pointing at it when he resided in Yumoto not as an artist but as a nuclear power plant worker, is presented in a different form. By uncovering Hamadori’s unique history at this exhibition, Takeuchi has “reversed” the no longer existent Mihako Theater into a corner of a different location within the same region. In other words, Demolition of Mihako Theater is at once a re-creation of the demolition of a theater that once stood in Yumoto and a reconstruction of the site of the recovery work following the Fukushima nuclear accident where Takeuchi was once present. (To be continued)