A Restatement: The Art of ‘Ground Zero’ (Part 31)

The Endless International Exhibition: ‘Don’t Follow the Wind’ Update (II)

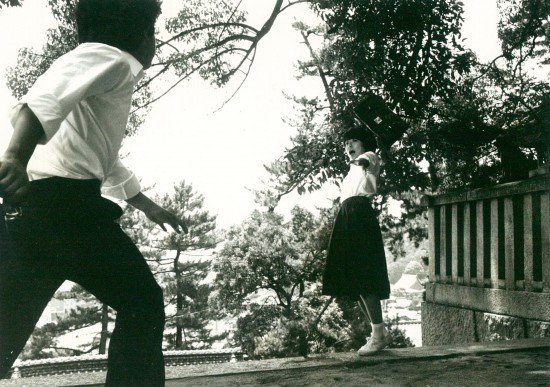

Nobuhiko Obayashi (center) on set during the filming of House (1977). Photo courtesy PSC/ Nobuhiko Obayashi Office.

Nobuhiko Obayashi (center) on set during the filming of House (1977). Photo courtesy PSC/ Nobuhiko Obayashi Office. Of course, I had known about Nobuhiko Obayashi for a long time. In particular, as a junior high school student, House (1977), which I scrambled into the local movie theater to see on opening day, had a huge impact on me. A cross between horror flick and teen heartthrob movie, it had a setting never before seen in theatrical movies. It was advertised on all manner of media prior to its release, building up the expectations willy-nilly of elementary and junior high school students who had just started their summer vacations. Still the movie far exceeded my imagination. It was not so much a horror movie, but a movie resembling an actual haunted house. So the impact was connected to realizing for the first time that a movie did not have to be a “play”; it could also be a “haunted house.” At that time, the Japanese movies opening at theaters around the country were controlled from production to distribution by the big entertainment companies like Shochiku and Toei, and as such they were still very much an extension of live theater. Their main selling points were the skilful performances and personal charm of their veteran actors (even in the monster movies aimed at children, the monsters were indispensable “lead actors”), and at the most, scrutinizing the directing abilities of the directors was about the only way to enjoy pretending to be a connoisseur.

H0NWIxl2VJk

Trailer for House (1977).

It was in this context that in an unprecedented move, Obayashi, an experimental filmmaker who had previously directed television commercials and who had absolutely no experience at the bottom of the ladder at any of the above-mentioned major film studios, was approached by one of those studios to make a feature film. Far from adopting a haughty attitude, he based his movie on ideas his 12-year-old daughter came up with after taking a bath, eventually launching on a massive scale at unsuspecting filmgoers all over the country the kind of anarchic movie experience (it is even unclear who the movie’s protagonist is) that completely contradicted Japanese film up until then. Regardless of how accustomed they had grown to monsters, aliens and cyborgs through television, it was inevitable that the adolescent generation for whom the potential of film was still unknown would be shocked. Sure enough, House provoked strong arguments for and against. In a sense this was the royal road to filmmaking, but for those of us who had not yet even heard the names Lumière brothers or Georges Méliès, there were aspects of the film that were far beyond our comprehension.

Later, I finally found out just what the dawn of cinema was all about, and by the time I learned that film was born on a line extending from spectacles such as panoramas and dioramas and that it was upon this that the virtual world of Hollywood with its reliance on artificial sets was realized, I was already a university student.

Even so, the shock I experienced when I saw The Girl Who Conquered Time (1983), also directed by Nobuhiko Obayashi, at a movie theater in Kyoto was no less impactful. Back then, when DVDs were non-existent, it was not unusual to go to three different theaters in a single day to watch three different movies. Moreover, 1983 was a particularly noteworthy year in the history of post-war Japanese cinema, with Yoshimitsu Morita’s The Family Game coming out in June and Shinji Somai’s The Catch hitting theaters in October, amid which The Girl Who Conquered Time opened in July. Even in this context this movie had a peculiar freshness that really stood out.

This is probably clear from the fact that the film – and dare I say it not the original book by Yasutaka Tsutsui – continues to have a strong influence even today, having been remade by many of the new generation of filmmakers, including Mamoru Hosoda. Above all, given that the premise behind Makoto Shinkai’s Your Name, the most talked about work in the Japanese movie industry in recent years, is like a cross between the final scene in Obayashi’s The Girl Who Conquered Time (the replacement of memories resulting from time travel and resistance to this) and the plot of Exchange Students, which Obayashi helmed the year before in 1982 (the genders of a boy and girl are suddenly switched though their appearances remain the same), no doubt more than a few observers sensed in it some major echoes from Obayashi’s films.

Exchange Students (1982), archival photos, courtesy PSC/ Nobuhiko Obayashi Office.

x6oZv0o80kY

Trailer for The Girl Who Conquered Time (1983).

The story of how I was “reunited” with Obayashi as a result of seeing the epic feature film Casting Blossoms to the Sky (2012), which astonished viewers and signaled another dramatic change in style for the director in the wake of the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, is something I have recounted on numerous occasions (including No. 27 of this column), so I will not repeat it here. The crucial thing is that the feeling of tension arising from getting the opportunity through Casting Blossoms to the Sky to meet Obayashi and get to know him, which was akin to not simply reviewing his films as a critic but having my very existence “cut in” to Nobuhiko Obayashi’s world and at the same time being given the role of “throwing back” the kind of chemical change that could only occur in what Obayashi himself refers to as “movies without ‘The End’ titles,” continues to hang over me to this very day. And for me, the one and only “entry” to this was “the exhibition that no-one can see” that opened on March 11, 2015, “Don’t Follow the Wind.”

From before the exhibition began I had occasionally mentioned and discussed with Obayashi this peculiar international art exhibition project that would “open” (ie, “close”) in the middle of the “difficult-to-return zone.” This was because it is obvious if one looks at the movies he has made since Casting Blossoms to the Sky that he has been touching far more directly on the issue of nuclear power than before. Moreover, Obayashi comes from Hiroshima, and while he was born and raised in Onomichi (”hometown”), which has been the setting for several of his films, because his family were doctors for generations, the situation surrounding exposure to radiation as a result of the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima was always a familiar reality for him; in fact, had he not become a film director but instead continued in the family tradition to become a doctor, he would have probably been involved in some form or another in helping the victims of the bombing. There is no doubt that Obayashi himself was more conscious of this than anyone. Even before Casting Blossoms to the Sky (or rather, from the very beginning, in House), scenes of the dropping of the atomic bomb have appeared repeatedly in Obayashi’s films to the extent that – despite being only a few minutes long, or rather precisely because of this – they have aroused a sense of unease in viewers. This naturally suggested that within Nobuhiko Obayashi the filmmaker something akin to “ill feeling” towards nuclear matters had long existed. The accident at TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear plant triggered by the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami meant that this “ill feeling” ceased being an “ill feeling” and turned into the most important theme in Obayashi’s career as a filmmaker (what Obayashi calls “cinema Guernica”) and was now being fully developed.

Let us not forget that Obayashi is none other than the original advocate of “hometown movies.” As such, he could hardly be expected to have not thought of the people who one day out of the blue found themselves unable to return to their “hometowns” due to contamination by radioactive material. Even if they were obliged to use such peculiar terms as “difficult-to-return zone,” for the people who once lived there these places were still the hometowns where they were born and raised. The reason Obayashi set Exchange Students in his own hometown of Onomichi and resisted and sought to prevent – even just a little – the passing of time is that he knew just how intimately connected hometowns are to the passage of time. Here, there was probably also a link connecting Exchange Students and The Girl Who Leapt Through Time. In Exchange Students, for example, even though a character’s gender identity was switched with another’s in the past, they seek to live “thereafter” without losing the memories they had at the time of the switch. And in The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, in return for being saved by the man she loves who has visited from the future at a time when she has become a nomad, wandering back and forth in time, due to having accidentally acquired the ability to time travel, the protagonist is faced with the crisis of completely forgetting about him forever. Condensed into both these movies is Obayashi’s unique concept of “time.” I sensed there was something in common between this and the “difficult-to-return zone” where, due to the evacuation order arising from the nuclear accident, the inside and outside of a “hometown” have been switched, just like a “transfer student” (the literal translation of the Japanese title of Exchange Students), with no one knowing when things would return to normal – or in other words remaining frozen in a state of “leaping through time” with the future uncertain.

As a critic whose only available tool is language, I felt the need to resist the inhumanity of the series of unfamiliar terms, of the countless curious concepts such as “vent,” “sievert,” “becquerel,” “decontamination,” “decommissioning” and “difficult-to-return zone” that have suddenly found their way into the Japanese language since the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, by giving them critical topicality. The reason I thought of asking Obayashi to become involved in “Don’t Follow the Wind” is none other than because between his thinking and creativity around the concept of time and the theme of hometown I thought it should be possible to critically understand afresh the “difficult-to-return zone.” However, for this to occur it was necessary to have him not only think about this project but to participate in it in some form. By this I mean that since “3/11,” as I had been made keenly aware of once again through Casting Blossoms to the Sky, I had become someone wandering about in “a fiction without a ‘The End’ title, ie, reality,” and the only way I could open up an exit from this was to appeal to Obayashi myself as a critic. However, regardless of Obayashi’s status as an artist who was intimately involved with “hometown movies,” the “difficult-to-return zone” was contaminated with highly radioactive material and was by no means the kind of place I could invite him to lightly. I was at a loss. In the end, though, it was Obayashi who threw the question at me. The occasion was a meal we had together before the summer of last year. “I’ve been waiting for a while now,” he said, “but exactly when are you going to invite me to this exhibition of yours?” (To be continued)