Architecture/Collage/Painting: Jun Aoki + Hiroshi Sugito’s phantom ‘Happa and Harappa’ exhibition

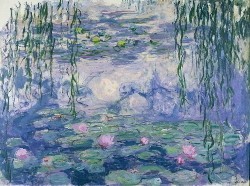

There is a famous essay by Colin Rowe and Robert Slutzky entitled “Transparency: Literal and Phenomenal.” Those who have come to understand from listening to others that the former term in the subtitle refers to architecture constructed out of materials such as glass that are “literally” transparent while the latter refers to architecture that “phenomenalizes” transparency through the power of architecture would be taken aback upon opening the original essay. The authors begin their discussion of the two transparencies by referencing works by Cezanne and works by Picasso and Braque from the period of Analytic Cubism. To help us follow their argument, let us first look at Monet. It could be said that the theme of the “Water Lilies” series of paintings that Monet completed towards the end of his life was filmic in the context of painting. By filmic I mean the sense that an image is on top of a transparent surface (a mirror, water). In these paintings, a transparent plane or layer that had never before been visible is laid bare by painting foreign bodies in the form of water lilies on top of the reflections on the water, which is rendered with a sense of movement.

Claude Monet – Water Lilies (1916-19

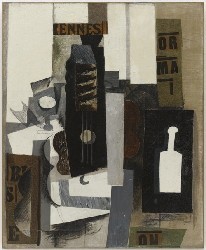

Through the addition of the water lilies, Monet phenomenalizes the “water plane.” Furthermore, he emphasizes the “picture plane” through the addition of willow tree branches that fall over the picture frame and draws attention to the “canvas plane” by deliberately leaving spots unpainted. In this sense, we could say there are as many as three layers in each of these paintings. At around the same time, Cezanne was creating paintings in which the layers are fractionalized/multiplied in accordance with such things as the location from which he viewed his subject (Mont Sainte-Victoire) and the passage of time, and in which these layers reflect diffusely like crystals while overlapping each other. Taking these ideas even further, in Analytic Cubism the picture plane is composed of complex, multiple layers as if photographs of a single object taken from various distances and angles had been laid on top of each other. Rowe and Slutzky’s distinction between literal and phenomenal transparency relates to the two possible states of these multiple layers. Let us look at the two examples they give:

Left: Pablo Picasso – Man with a Clarinet (1911)

Right: Georges Braque – The Portuguese (1911)

In Picasso’s Man with a Clarinet (1911), the multiple layers embedded in the picture plane are drawn by the gravitational pull of the phenomenon of the “clarinet player,” and cohere around it. Resultantly, two sets of transparent layers – the foreground layers and the background layers – emerge on the picture plane. Rowe and Slutzky use the term “literal transparency” to refer to the condition whereby we are able to separate these transparent layers and determine which are closer and which are further away. Contrastingly, in Braque’s The Portuguese (1911), the multiple layers overlap each other without exception, and the phenomenon lies scattered among these overlapping layers. We are unable to determine with certainty the relative depth of the layers, a condition Rowe and Slutzky refer to as “phenomenal transparency.”(1) One could say that artists such as Cezanne and Braque developed the “literal transparency” of Monet’s water lilies into “phenomenal transparency.”

Now, as is generally known, with 1912 as a crucial year, Cubism evolved from Analytic Cubism, which gave rise to constructions and papier collé/collage, which in turn led to Synthetic Cubism. (2) 1) Objects were added to the picture plane, as a result of which the previously unseen structural plane or layer was laid bare. Monet laid bare the plane or layer of water by “collaging” water lilies. Analytic Cubism was the composition of layers. 2) Constructions are works in which masses recognized as phenomena (guitars, people, etc) were extracted from amidst these layer compositions as polyhedrons. The “literal transparency” of two-dimensional layers was lost, and in its place a different dimension, namely the dimension of meaning, was introduced. In this dimension, the viewer is not only aware of the phenomenon in the picture, but is also aware of the space and relationships surrounding it. And 3) fragments of the construction are collaged disjointedly on the picture plane along with various other materials. This process can basically be understood as the shift from “literal transparency” to “multi-layered objects” or “phenomenal transparency” by way of “polyhedrons.”

Overlapping layers are abstracted into three dimensions and lose their “literal transparency,” although this is reconverted into “phenomenal transparency” through collage.

Pablo Picasso’s construction Guitar (1912)

Pablo Picasso – Still Life with Chair-Caning (1912), collage of oilcloth printed with a chair-caning pattern, oils, paper and rope (as framing) on oval-shaped canvas

Pablo Picasso – Glass, Guitar, and Bottle (1913), oil, pasted paper, gesso, and pencil on canvas

White paper -> the collaging onto this of strips of paper -> the layering of the sections of white paper that remain -> the drawing of a guitar in such a way that it traverses the strips of paper and white paper -> the layering of the “white paper and strips of paper” not covered by the drawing…and furthermore, the layers do not overlap each other in sequence from the top (ie, they do not constitute literal transparency). In the march towards “phenomenal transparency,” the collage process progresses in such a way that the dimensions of meaning and layering intersect each other. The symbols, line drawings and shadows that suggest phenomena are executed in such a way that they straddle the layers and deny any top-to-bottom relationship, and consequently both the relationship between the layers and the location of the phenomena continue to change. “The strips, the lettering, the charcoaled lines and the white paper begin to change places in depth with one another, and a process is set up in which every part of the picture takes its turn at occupying every plane, whether real or imagined, in it.(3)

Unlike postmodern architecture, collage does not entail composition based on a heterogeneous mixture of elements. It is a discontinuous process comprising the exposure and ongoing renewal of previously unperceived underlying frames (environment in the broad sense of the term, including layers, pedestals and floors). As well, all the relationships and meanings inherent in collage arise from the transition in which one arrangement is continually replaced by another, or in other words the multi-layeredness in which the horizontal relationship simultaneously overlaps. Collage is a “(pasted paper) revolution” because it brings about a kind of severance in our consciousness and because its multi-layeredness dismantles the unit of identity of “1.”

Jun Aoki’s Aomori Museum of Art is collage. Its white exterior is cut open here and there to reveal the glass walls, structural steel frame and curtains in the background. As a result, the continuity of the uniform exterior is broken, and the walls take on the appearance of a thin cover (layer) draped over the museum. The incisions serve the same function as a collage, the exterior manifesting itself as four layers (literal transparency), namely: white walls, glass, steel frame and curtains. However, these walls are made of bricks and are painted white, which is at variance with the thin film sensation of the phenomenalized “layer.” At the same time, the strong materiality of the bricks is also obfuscated by the white paint, and ultimately the double negative of the exterior being made of bricks despite being layered and not looking like it is made of bricks despite being so introduces variability to the meaning of the exterior (confusion at the level of meaning).

In spite of this the main feature of this art museum would appear to be the four layers of flooring sandwiched just like a collage between the two layers of the unevenness of the earthen trenches and the unevenness of the white superstructure draped over the top of these. Look at the collages of Braque and Picasso. Aoki has collaged the floor surfaces as if they were oil, paper, pencil or gesso, and collaged the shapes of the windows, roofs and openings as if they were glasses, guitars or bottles. Because they penetrate freely the unevenness associated with the spatial depth, the four layers take on a collage-like condition, undermining visitors’ experience of their relationships with the layers (the perception of which floor they are on). In addition, because the internal walls are earthen or white like the floors, and the brick surfaces of the external walls also appear as internal walls, the spatial relationship of the layers becomes even more complicated. The Aomori Museum of Art is a collage field in which the inside surfaces of the external walls covered in “literal transparency” are replenished with “phenomenal transparency,” renewing the meaning of the space as the angle changes from the point at which one views it. “Harappa”(4) is the condition of being open to the next strip of paper or the next manipulation in collage as a process. As for the next strip of paper, or the next manipulation, Aoki left this up to Hiroshi Sugito, and the results were to have been unveiled at the “Happa and Harappa” exhibition.

-

Colin Rowe, “Mannerism and Modern Architecture,” trans. Toyo Ito and Yasumitsu Matsunaga (Tokyo: Shokokusha, 1981) 211, 215.

- Pierre Daix and Joan Rosselet, Picasso: The Cubist Years, 1907-1916, (London: Thames and Hudson, 1979), p.94, 118; William Rubin, Picasso and Braque: Pioneering Cubism, (New York: MoMA 1989), p.30; Mari Komoto, Setsudan no jidai: 20 seiki ni okeru kolaji no migaku to rekishi [The age of severence: The aesthetics and history of collage in the 20th century] (Brucke, 2007), 140-142.

- Clement Greenberg, “The Pasted-Paper Revolution,” in The Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 4, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 63.

- Jun Aoki, Harappa to yuenchi (Vacant lot and amusement park), Harappa to yuenchi 2 (Vacant lot and amusement park 2) (Tokyo: Okokusha 2004, 2008). Many commentators have interpreted these concepts of Aoki’s in terms of the modern duality of “system” (system appropriate for a purpose) and “other” (an undifferentiated state, freedom full of possibilities), but his concept of “harappa” actually attacks this duality itself, or in other words, the complicity of functionalism and freedom (a “yuenchi” or “theme park” is a form of architecture where “playing freely” is “a given”). “Harappa” is not a free place full of possibilities, but a metaphor for the “present” rendered multi-layered through the collaging into the former state (the past) of the next state (the future). “A state in which there is only present time” (Harappa to yuenchi 2) is the temporality of collage, and is unrelated to “here, now.”

Archive

Critical Fieldwork: Observations on Contemporary Art in Japan 1-6