How to abandon Japan: ‘Yasuo Kuniyoshi from the Fukutake Collection’

at the Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art

This exhibition of works by Yasuo Kuniyoshi at the Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art is extensive, ranging from anti-Japanese campaign posters created during World War II as a display of allegiance to the US to a collection of oddly colorful works painted in the period following the war to the artist’s death in 1953. Never before have I seen these hitherto largely ignored works displayed together like this (although they have been shown previously, at the same museum in 2006, and at the Gunma Museum of Art, Tatebayashi, in 2008). They call to mind the unrestrained desire and unbearable conventionality observable in the curious paintings of children and religious icons produced after the war by Tsuguharu Fujita (aka Léonard Foujita), although as a collection they have a different disagreeability to that of Fujita’s paintings, by which I mean they have the disagreeability of manifestly masochistic self-portraits, and can only be described as pitiful.

There is no doubt that the reasons these works – from the twilight years of a “Japanese” who succeeded in every sense of the term as an “American artist” – are so patently hollow stem from the Pacific War. For this reason one could call these works “an expression of the identity crisis of an artist torn between Japan and the US on account of the war.” Despite thinking of himself as an “American artist,” Kuniyoshi was considered “Japanese” pure and simple following the attack on Pearl Harbor. When push came to shove, “yellow Caucasians” were yellow. And yet if this were the only issue at stake, surely he had already experienced this: in 1919 when his first wife lost her US citizenship due to her marriage to him; in 1922 when the Supreme Court ruled that Japanese could not become US citizens; and in 1924 when the Johnson-Reed Act came into force, prohibiting the immigration to the US of Japanese and other Asians. Above all, Kuniyoshi himself, who arrived in the US at the age of 17 having abandoned his country of birth, was never able to gain US citizenship. And yet this same artist was able to state, “In appearance, I am Oriental but my beliefs, ideals and my sentiments have been shaped by living in the free American atmosphere most of my life.”

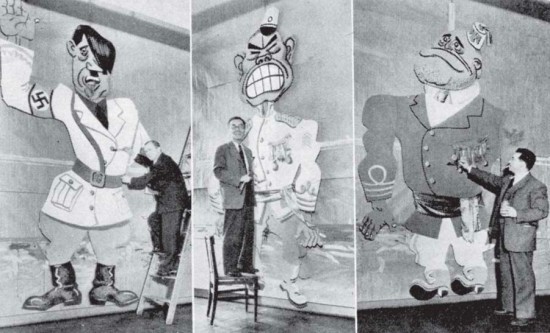

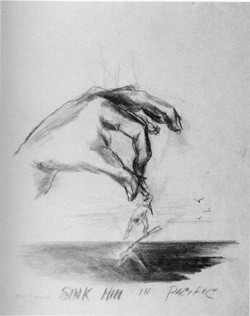

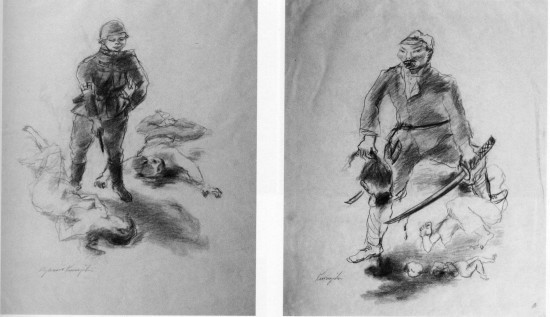

By “the free American atmosphere,” Kuniyoshi probably meant the liberalism of the New York art world bolstered by its Jewish brand of internationalism. For Kuniyoshi, “America” was a society of fairness based not on identity stemming from race or nationality but on money and linguistic ability and talent, a society of human freedom comprising people who “didn’t have to belong.” It wasn’t that he identified as an American. Having produced drawings of Japanese being picked up and dunked in the Pacific Ocean and of Japanese troops beheading, raping and intimidating others, having abandoned Japan and the Japanese language to the extent that in 1942 he wrote in English scripts for radio broadcasts directed at Japan as part of the anti-war campaign, and having contributed a giant caricature of “Hirohito” to accompany those of Hitler and Mussolini by George Grosz and Jon Corbino respectively, Kuniyoshi believed in the freedom and justice of a world in which everyone was an immigrant, producing these and other works as a “citizen of the world” free of nationality, to which extent he had exempted himself from the very notion of national identity.

Yasuo Kuniyoshi (center) in Time, April 20, 1942. (1)

During the war itself, Kuniyoshi, who had powerful connections due to his status as a distinguished artist (his acquaintances included childhood friends of President Roosevelt), was in a far more advantaged position compared to the Japanese-Americans living on the West Coast who were sent to internment camps. However, the various responses in American society to the events that began with Pearl Harbor taught him that the “America” he believed in was a tenuous fiction. The kind of place where people “didn’t have to belong” never existed in the first place. Kuniyoshi woke from his dream.

Incidentally, modern Western colonialism assumes a priori the binary opposition of the West and the non-West. Accordingly, the essence of the discrimination that underpins colonialism lies not in the exclusion of non-Western culture, but rather in the embracing of it as an adversary in the form of a requisite “other.” Because the dark aspects and fringe elements of one’s own culture are naturally projected onto one’s “adversary,” the West today respects any number of differences between itself and others, but if there is one thing it definitely will not recognize, it is the possibility of sameness, that it is even partially African, Arabian, Asian (Orientalism). This is why “citizens of the world” in colonized lands who encountered modern Western society and were consequently emasculated (became “adults”) were forced by the modern West before anything else to identify as this “other.” From this derives the warped state of the traditional Japanese-type cosmopolitan, or J-cosmopolitan. Having been emasculated by Western culture, their types are world standard cosmopolitans in all respects except that under no circumstances can they identity as Western (males). Their position is warped into that of “grown-up women and children.” To put it another way, their role is to act as “the Western other” in the eyes of the West, and as “Westerners” who have taken on the role of embodying adult Western modernity in the eyes of Japan. For Westerners, “the Western other” is plainly “Japanese,” but for J-cosmopolitans this is not the case, and this inconsistency is the tragedy of the J-cosmopolitans.

Because Yasuo Kuniyoshi abandoned Japan at an early age, and the formation of his character took place in the US, where he seemed to be living a life that embodied the American dream, one could say that he was spared the kind of colonialism and emasculation outlined above. In fact, unlike artists such as Ben Shahn and Edward Hopper, Kuniyoshi’s style in the 1920s and ’30s, while employing any number of indigenous-like motifs, remained an American version of the international style, not dissimilar to that of van Dongen, Klee and Chagall. The Pacific War swept away the internationalism Kuniyoshi believed in as if it were a sandcastle, forcing him to confront the issue of colonialism, or in other words the binary opposition of “America” versus “Japan,” which inevitably compelled him to identify as “Japanese.” This is what it meant for him to “wake up from his dream.” To act as “the American other = Japanese” in the eyes of America, and as “the American” who had taken on the role of embodying adult America in the eyes of Japan. This was what “internationalism” now meant as far as he was concerned, and explains the anti-Japan campaign posters, the radio broadcasts and so on.

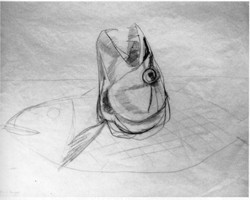

What is ironic is that post-war America acted in such a way towards Kuniyoshi after he had woken from this dream that it accentuated the very illusion of “America” that had already been destroyed in his own mind. In other words, America identified Yasuo Kuniyoshi anew as a leading American artist. In 1948 he was the subject of a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the first time such an exhibition had been held at the museum for a living artist, and in 1952 he was chosen as an exhibitor at the US Pavilion at the 26th Venice Biennale. However, it is doubtful whether such institutional honors made an impression on the disillusioned Kuniyoshi. For Kuniyoshi, things had reached the stage where living in America was nothing but an unseemly farce that involved putting on and removing “Japanese” and “American” masks. As the buffoon in this farce, he was constantly being caricatured by his own artwork, just as “Hirohito” had once been caricatured by it. His use of color underwent a complete change: the picture planes in which color had formerly been used to bring about contrast with restrained, lyrical tones were replaced by flat picture planes lacking in contrast that looked as if bright colors (including a distinctive “yellow”) had been rubbed onto the canvas, and alongside such lurid motifs as a young woman (symbolizing the artist immediately after the war) being attacked by a “white” praying mantis and a “black” locust; a lopped-off fish head – Japanese motifs such as Rising-Sun flags and carp streamers surrounded by rubble began to appear in a way that is almost pitiful. These bleak works tinged with listlessness and feelings of impotence are none other than groans of self-torment and self-mockery directed at Kuniyoshi himself following his transformation into a J-cosmopolitan.

In fact, 1952 was the year Harold Rosenberg’s famous essay, “The American Action Painters,” was published in Art News, right when the new identity of the “American artist” was on the verge of being established. The process whereby abstract expressionism came to represent American contemporary art left Yasuo Kuniyoshi and the other “American artists” of the pre-war generation behind.

Artwork for war posters

Left: Sink Him in Pacific (1942). Right: Clean Up this Mess 1942

Left: Slain Women (1943). Right: Beheaded (1943).

Drawings

Fish Head (1952)

Sword Swallower (1951)

Paintings

Little Girl Run for Your Life (1946)

Here is my playground (1947)

‘Yasuo Kuniyoshi from the Fukutake Collection’ was on display at the Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art from July 15 to August 21.

-

Wang Shipu, Becoming American? The Art and Identity Crisis of Yasuo Kuniyoshi (Honolulu: Hawaii University Press, 2011).

Archive

Critical Fieldwork: Observations on Contemporary Art in Japan 1-6