Co-founder in 1975 of the Rotterdam-based firm Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), Rem Koolhaas is known not only for producing designs and masterplans of radical innovation, but also for radically innovating contemporary architectural practice through his numerous publications and exhibitions. Koolhaas first achieved broad international recognition through his book Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan (1978). In this and subsequent publications such as S, M, L, XL (1995), which brought together two decades’ worth of diary entries, essays and architectural plans, he has established himself as a protean thinker and lucid, entertaining writer. Dedicated to further developing the intellectual life of architecture, in 1998 Koolhaas established as a subsidiary of OMA the think-tank AMO, through which he has continued to carry out research, publishing and exhibition projects.

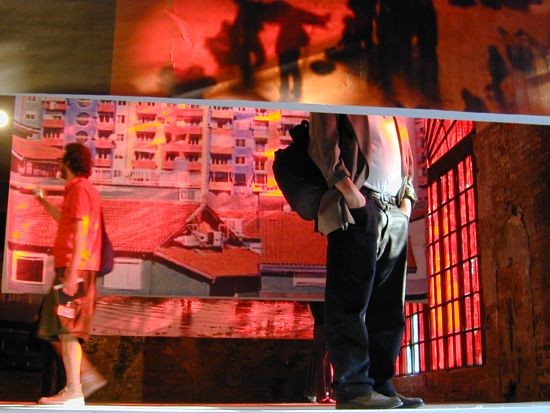

And while trends in both contemporary art and architecture exhibitions continue to converge on the one-off, large-scale installation, Koolhaas’s approach to exhibition making is fully integrated with all other phases of his practice. Often filled with oversized collages combining lurid imagery and polemical, yet pithy texts, exhibitions such as “Content” (Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, 2003 / Kunsthal Rotterdam, 2004), “The Image of Europe” (premiered in Brussels, 2004 / toured Europe) and “OMA in Beijing” (Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2006) function equally as artistic statements and blistering analyses of the contradictions of sense, behavior and structure that inform the everyday environment. What both publications and exhibitions make clear is that, rather than attempting to impose an order upon these contradictions, Koolhaas sees them as a terrain for generating new forms of architecture.

The impact of this approach has been particularly evident in Japan, despite the fact that OMA has only one built project here, the Nexus World Housing (1991) in Fukuoka, part of a superblock of residences overseen by Arata Isozaki. Japanese architects across several generations cite Koolhaas as a critical inspiration. Speaking with ART iT, Ryue Nishizawa said, “Rem influenced me right when I was trying to decide whether to commit to architecture. It was the end of the 1980s and the start of the 1990s, and his architectural works, books and exhibitions all energized us students.” Referring to a visit to the 1995 survey of OMA’s projects at the private exhibition space TN Probe, “OMA in Tokyo: Rem Koolhaas and the Place of Public Architecture,” emerging architect Junya Ishigami told ART iT, “A Koolhaas exhibition is always distinct from those of other architects, communicating a powerful sense of vividness and immediacy. That experience profoundly affected me at the time.”

Nishizawa’s and Ishigami’s sentiments have been underscored by the honoring of Koolhaas at this year’s 12th Venice Architecture Biennale with the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement, on the proposal of artistic director Kazuyo Sejima. Surprisingly, Koolhaas did not exhibit at Venice until 2005, when he was included in the Art Biennale, but since then he has been a frequent participant, presenting projects four times in the past five years. In recognition of his Golden Lion, ART iT has compiled an archival presentation of Koolhaas’s projects for Venice, in collaboration with OMA*AMO.

*Unless otherwise noted, all images © and courtesy OMA.

TIMELINE:

2005

EXPANSION/NEGLECT

51st Venice Art Biennale

Does every museum in the world need to be modernized?

Do all museums have to adhere to the same technical conditions?

Do all museums have to be extended and updated?

Or can a certain amount of inaction – a certain resistance to change – actually be instrumental in maintaining a degree of the authenticity so frequently erased by modernization?

Can the architect, a person usually hired to change the conditions he finds, perform more like an archaeologist, scrupulously examining the current conditions, and proposing new forms of organization that allow each element to enjoy renewed value?

The Hermitage project cannot be understood in strictly architectural terms; in fact, it cannot be understood along any of the classical definitions of a project. The “Hermitage Project” is not a project: it is a concentration of different issues that can only be resolved successfully by taking a more comprehensive approach – curatorial or intellectual. Rather than a confident imposition of the new, the task at hand is to find those changes that will allow the Hermitage, without being too manifest, to function better.

During the last three years, AMO/OMA has worked as a consultant for the Guggenheim-Hermitage Foundation on scenarios for the museum’s future. The central issue at stake is how to modernize the Hermitage Museum while accepting one of Russia’s great legacies on its own terms. The Hermitage is examined as a whole: its functioning as a museum, its future position, its integral participation in the city of St Petersburg…

Captions for All Panels

1. (Dow Jones vs Museum expansions)

Largely because of economic circumstances, the Hermitage did not participate in the late 20th-century museum boom. Immune to fluctuations in the world economy, the Hermitage avoided turning itself into a commercial enterprise.

2. (Most space, most art, most exhibitions, least visitors)

Of all the great museums, the Hermitage sustains the largest collection, the largest number of exhibitions, and the most space with the least amount of visitors.

3. (Museums revenue and support)

In comparison to other great museums, the Hermitage’s commercial activities are reduced to a minimum. This provides an opportunity to establish the Hermitage’s global identity by distinguishing it from other world-class museums.

4. (Increase of Hermitage m2, Tsarism, Communism, Free Market)

Historical changes guaranteed the Hermitage’s existence as an exclusive enclave, set apart from contemporary events and devoted to preservation of the past. Free market capitalism, coupled with the museum’s largest expansion ever, raises the question of whether to modernize the museum or retain its original character.

5. (View out of window onto palace square)

So far, modernization has passed the Hermitage by. The buildings’ relative neglect has helped to create a unique condition: enabling a confrontation with art more direct and more authentic than in more “modern” museums.

6. (Malevich between curtains, insert: Malevich with woman)

Black Square by Kazimir Malevich – exhibited in a highly decorated room under fluorescent lighting – is one of the most valuable statements of the 20th-century and emblematic of a new relationship between modernity and the past.

7. (Palace square with all Hermitage’s buildings)

Palace Square will become the center of the museum complex. The historic events that have happened here make the Hermitage not only a museum of art, but also an institution embodying Russian history.

8. (1200+800 rooms)

Continuing the Hermitage tradition of discovery through reinvention, the General Staff Building will add a vast number of spaces never intended for the display of art.

9. (Rooms in section)

The reservoir of rooms in the combined Hermitage presents an endless variety of spatial typology and quality. Some interiors are protected, others practically derelict.

10. (RK in neglected room)

To avoid the rupture between the past and the present, ruined sections of the building can be tactfully maintained.

11. (Rooms vs collection)

3,500,000 pieces of art and artifacts and 2,000 rooms…this condition can generate a vast repertoire of installation and curatorial concepts.

12. (Table with applied art)

A scrupulous investigation of the museum properties could determine how to limit change and how to mobilize the Hermitage properties. The Hermitage: a prototype, not of the ideal museum, but of an endless collection of pertinent conditions.

13. (Art in neglected room with Wallpaper)

By putting some of the most valuable works in some of the most distressed areas, unexpected conditions can encourage accidents and experiments in how to display art.

14. (Spiral table below chandelier)

Sterile conditions of “modern” museums prevent viewers from considering art in other ways. Scholarship and recreation boundaries could be blurred to go beyond dominant ways of display.

15. (Impressionist’s portraits wunderkammer, insert: Malevich wunderkammer)

The Hermitage can reinvent Modernity, not in terms of style, but in terms of finding an intelligent use for existing spaces.

16. (Electronic devices closed doors)

The project could define a way to navigate through the building’s rooms without resorting to traditional forms of architectural hierarchy. New, invisible technologies can provide innovative museum-wide strategies.

17. (cut floor collage)

The Hermitage must consider whether there is the necessity of adding more building to the building. The careful study of the possibility of carving in the existing building could reveal new spatial potentials for displaying art in the General Staff Building.

18. (Foster’s British Museum)

The British Museum: the typical preservation project. Although its goal was to enhance the existing building, the gulf between preservation and modern architecture resulted in an addition which reduces the qualities of the old.

19. (Atriums for everything)

This is only one particle of an expanding universe of “respectfully” treated historical buildings. The decision to cover courtyards is now a banal and overly used device for modernization. The State Hermitage Museum is too exceptional to settle for the expected.

20. (2 courts vs 4 courts)

Intervening in two, instead of five, courtyards will reduce: the amount of demolition; the air-controlled volume; and development costs. Limiting architectural intervention also increases the potential for preservation.

21. (Big room view in blue foam)

The Museum’s need for bigger spaces – where the crowds will be largest or the art the grandest – could be achieved in a more compact and environmentally sustainable manner.

22. (Aerial view of implant)

A new structure, independent from the existing building, will allow all modernization to take place locally and will allow modern technical standards to be met within a new building;…

23. (Phased effect of implant)

…it will also reduce pressure on the existing building to conform to current technical standards, allowing a gradual upgrading of the existing building over time as development finances become available.

24. (white interior of implant)

The interior of the new big room is completely sealed from the outside, providing a complete artificiality of conditions. The room can adopt almost any identity: the prototypical 20th-century-white-room-modern-art-gallery…

25. (Wunderkammer)

…but also a 21st-century version of the Wunderkammer.

26. (Piotrovsky letter)

Directive from above…Less extras, more exhibition, please!

27. (Carving model with negative as insert)

With the program now substantially smaller than the existing building, to add more area to the building becomes questionable. Could the adaptation of the General Staff Building be a matter of subtraction?

28. (Diderot)

A resource manual could guide intervening in the General Staff Building. A set of simple ideas could trigger new and more efficient ways of experiencing art in the Hermitage as a whole.

29. (Carving)

Implementation and mixing of these resources could generate countless options…

30. (Carving)

…that would radiate through the entire experience of the building.

Credits

Partners: Rem Koolhaas and Reinier de Graaf

Team: Alexander Reichert, Holger Pausch, Emilie Gomart, Joao Leal Bravo da Costa, Mendel Robbers, Samir Bantal, Felix Madrazo, Brendan McGetrick, Jens Hommert and Todd Reisz

2006

THE GULF: HEDGE FUND STUDY

10th Venice Architecture Biennale

A coastal analysis reveals a new regional and global order of effort, conceptualization and rivalry that needs to be acknowledged.

THE GULF is the current frontline of rampant modernization: a feverish production of urban substance on sites where nomads roamed unmolested only half-a-century ago.

THE GULF – its initial development triggered by the discovery of oil – is undergoing hyper-development to ready for oil’s imminent depletion.

GULF CITIES are in construction now. This means they are, inevitably, based on the repertoire of current urban prototypes – community (themed & gated), hotel (themed), skyscraper (tallest), shopping center (largest), airport (doubled) – cemented together by Public Space, extended soon with boutique, museum franchise and masterpiece.

In its current state, THE GULF is a landscape of vast means and ambition translated with gargantuan effort in ambiguous and sometimes disappointing results, a kind of farewell performance of an “Urban” that has become dysfunctional through sheer age and lack of invention.

But for that very reason – call it historical inevitability or sheer coincidence of timing – THE GULF will also be the terrain where the current architectural repertoire are so blatant, comprehensive and destructive that it has become unthinkable to rely on them as a toolbox.

Eventually, THE GULF will reinvent the public and the private: the potential of infrastructure to promote the whole rather than favor fragmentation; the use and abuse of landscape – golf or the environment? – the coexistence of many cultures in a new authenticity rather than a Western Modernist default; experiences instead of Experience™ – city or resort?

*

The world is running out of places where it can start over.

We live in an era of completions, not new beginnings.

Sand and sea along the Persian Gulf, like an untainted canvas provide the final tabula rasa on which new identities can be inscribed: palms, world maps, cultural capitals and financial centers.

The West suffers from a double neglect towards this land of opportunity: a refusal to take seriously something actually originating in the West and, subsequently, an inability to detect a rising global phenomenon.

Recent Gulf developments, much like Singapore and China in the 1980s and ’90s, have been met with derision: “Las Vegas in Arabia”(1), “Lawrence of suburbia”(2), “a bubble built on debt” (3), “skyline on crack” (4) and – most damning – “Walt Disney meets Albert Speer” (5), echoing the condemnation 15 years ago of Singapore as “Disneyland with the death penalty” (6). The recycling of the Disney fatwa says more about a stagnation of the Western critical imagination than it does about GULF CITIES.

To be a critic today is to regret the exportation of ideas that you have failed to confront on your own beat, from your own backyard. Ironically, the vast majority of developments these critics deplore have originated and become the norm in their own countries.

Is it possible to view THE GULF’s ongoing transformation on its own terms?

As an extraordinary attempt to change the fate of an entire region?

THE GULF is not just reconfiguring itself; it’s reconfiguring the world. Each of these GULF CITIES has been synthesizing versions of the 21st-century metropolis and now exports its own versions on an equally colossal scale to parts of the world modernity has not reached so far – from Morocco to Thailand.

This burgeoning campaign to export a new kind of urbanism – to places immune to or ignored by previous missions of modernism – may be the final opportunity to chart a new blueprint for urbanism. Will architecture grasp the last chance?

Credits

Curators: Rem Koolhaas, Reinier de Graaf, William Todd Reisz, Kayoko Ota

Collaborators: Hausatu Abdul-Karim, Ademide Adelusi-Adeluyi, Natalie Al Shami*, Jason Atkins, Samir Bantal, Tomek Bartczak, Anne-Sophie Bernard, Andrea Bertassi, Katrin Betschinger, Ezra Block, Fernando Donís, Talia Dorsey, Martin Gallovsky, Maisa Jarjous*, Lily Jencks, Ravi Kamisetti, Sara Kasa*, George Katodrytis*, Julie Kaufman, Jan Knikker, Barend Koolhaas, Daniel Klos, Sara Martin, Miho Mazereeuw, Cristina Murphy, Banah Mustafa*, Charles-Antoine Perreault, Daniel Rabin, Marieke Rietbergen, Guillaume Yersin

*American University of Sharjah

Sponsors: The Architecture Fund (HGIS Program from the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and of Education, Culture and Science, the Netherlands), Van Oord nv, Rakeen Development / RAK Promotion Board and Fondazione Prada

Satellite photo: MDA Federal Inc.

2008

LA DÉFENSE AND SANT’ELIA MASTERPLANS

11th Venice Architecture Biennale

A Heart for La Défense

The business district, while struggling to maintain and expand its position on the international scene, needs a focal point, capable of bringing it together as well as distributing it. A pump. A heart.

La Défense embodies the space to make that new heart possible. Below the deck lies a hidden and unsuspected world that has long been ignored and underutilised. That underworld is possibly La Défense’s most valuable asset today.

The deck, a volume rather than a mere surface, becomes a linking body that cements everything together, like an airport terminal. It continues to contain the transportation tracks and platforms, including our proposed internal shuttle that extends to Les Groues, the neighboring district.

Above all, the deck’s underworld becomes a lively and welcoming space, filled with daylight, where shops and lobbies converge towards the new central stop. An improved signage makes it more convenient for the user to find their way. The awakening of the deck’s unconscious provides a heart for La Défense.

This long needed nodal point allows La Défense to focus on becoming again what it was created to be in the first place: a compact, attractive, efficient and sustainable business center.

The new towers planned on the site leave no doubt that the district possesses the architectural resources to renew itself. For the renewal to be successful it needs to address the transportation and infrastructure issues and improve the (internal) accessibility of the district. When comparing La Défense to other business districts, the transit stops are too far apart, especially given the importance of the pedestrian. We propose to create a new central stop, right in the middle of the district.

Les Groues, which in our proposal is well connected to La Défense, can function very much in the same way as La Défense once served Paris. It can accommodate all functions for which there is no space within La Défense’s perimeter. Programs such as the station, nightlife, a park and the university, as well as functions that need a much looser development framework than La Défense can offer, such as smaller, more mixed-use, and more individual, developments. This benefits both Nanterre and La Défense.

The search for mixed-use programs throughout the years hasn’t proved fruitful. It has created a suboptimal environment with a relatively low density, security issues and unattractive pedestrian connections. Mixed-use architecture shouldn’t be any longer pursued within the very limits of La Défense. Like the defragmenting of a hard disk, the functions are to be reorganized in a cleaning process, freeing space for an optimized functioning of the entire system. The office towers are concentrated and intensified inside the Boulevard Circulaire, where housing is only maintained on the southwest triangle.

La Défense, a symbol of French modernity, maintains an ambiguous relation to history. L’idolâtrie de l’Axe historique has caused the district to shut itself off from its environment. The historical axis is multiplied to turn the business center into a new pivotal node of a larger urban network, that of Grand Paris.

Re-qualification of the Sant’Elia neighbourhood in Cagliari, Italy

The ambition of the masterplan is not only regeneration of an under-valued area and community, but also to exploit the full potential of this spectacular waterfront site for the benefit of the entire region, while improving social and environmental conditions of the current inhabitants and local nature.

The re-qualification of the neighborhood of Sant’Elia aims at the re-qualification of its bad image connotation “within” the city of Cagliari.

The solution to the problem is in creating jobs, empowering the population, formalizing informal activities and retaining the static energy of the locality. The solution should be found in the understanding of the present social discomfort and using it as a possible instrument for further design studies.

The majority of the residents want to stay in the Sant’ Elia neighborhood, land of unlimited freedom and creativity, as opposed to the formal city. The residents are continuously engaged in changing and adapting their environment to their very special needs. This is made possible by the absence of regulation and administrative presence on the site.

Our scope as designers is to keep this energy flow moving and introduce spaces and opportunities allowing the legalized continuity of such mansion. Encouraging and slightly modifying elements that do work on site seems to be an appropriate system for reintegration.

The often-exaggerated negative images of Sant’Elia, partially responsible for the residents’ hostility towards the city, could be switched into a positive image by bringing new interest to the area. Increasing the residents’ sense of belonging and responsibility needs to be implemented in the spatial materialization for a new masterplan.

The OMA project focuses on accommodating the edges of the site by eliminating distances and isolation and creating new proximities and confrontations with the ultimate ambition of offering a new, fresh, animated piece of Cagliari to the Cagliaritani.

Credits: La Défense

OMA – Office for Metropolitan Architecture

Partners-in-Charge: Rem Koolhaas and Reiner De Graaf

Associate: Clement Blanchet

Team: James Leng, Tudor Vlasceanu, Peter Stec, Sebastien Berthier, Pierre de Brun, Maurizio Mucciola, Caroline Martin, Konrad Krupinsky, Sandra Bsat, Joris De Baes, Billy Guidoni

ONE ARCHITECTURE

Principal: Matthijs Bouw

Project Architect: Selma Maaroufi

Team: Joana Bastos, Max Cohen de Lara, Tjeerd Haccou, Maxim Hourani

IRMA BOOM

Irma Boom

Julia Juriga-Lamut

SETEC PARTENAIRE DEVELOPPEMENT

Director Jean Paul Lebas

Martin Schoeller

CVA

Dominique Boudet

CRITIC

Francoise Fromonot

Credits: Sant’Elia

Partners: Rem Koolhaas, Floris Alkemade

Team: Andrea Bertassi, Philippe Braun, Andrea Massa, Cristina Murphy, Frederik Spilt

With: Ania Brault, Abigail Karcher, Rob Daurio

2010

CRONOCAOS

12th Venice Architecture Biennale

References

- Brown Journal of World Affairs, Fall/Summer, 2005

- Forbes, October 31, 2005

- Time, March 13, 2005

- Vanity Fair, June 2006

- Mike Davis, www.tomdispatch.com

- William Clinton, Wired, Sept/Oct 1993; Bidoun, Fall 2006