By Kyoichi Tsuzuki

There are certain individuals who in their youth avoid any place associated with karaoke, stubbornly preferring to remain cool and aloof by refusing to sing even when taken to such establishments, but who upon reaching middle age suddenly develop an inexplicable passion for karaoke and cling just as stubbornly to the microphone, to the amazement of all who know them.

Actually, come to think of it, there are quite a few people like that. I suppose you could liken them to guys who didn’t chase enough girls when they were young: the less they got laid back then, the more skirt they crave as they grow older. But to my mind the allure of karaoke, which can seduce the most discerning gentleman into abandoning all discernment, lies in its lyrics. Only a man hurtling headlong toward middle age, painfully aware that from here on it’s all downhill, could relate to Kenichi Mikawa’s state of mind as he warbles, “At least give me some cash before you say goodbye, you know you’ll feel better for it toooooo…”

Every karaoke fan understands that wailing through one of Mikawa’s soulful numbers while sitting at a bar clutching a whiskey and water is infinitely more intense than listening to him on an iPod. Perhaps karaoke was created to elevate the power of song to a higher plane.

The second half of the 20th century was marked by a musical revolution. Rock, which thanks to the electric guitar allowed anybody to make lots of noise with minimum effort, shook the foundations of what had been the domain of the professional musician. The hip-hop turntable destroyed the notion that one had to be able to play an instrument to make music; ditto rap for singing ability. Meanwhile it was the magical karaoke machine that turned on its head the hitherto universally accepted idea that songs were something professionals sang and others listened to. Who could have predicted in 1971 – the year Jim Morrison died – that karaoke, emerging from an obscure corner of Osaka, would do more to change the world than John Lennon asking us to Imagine, or Led Zeppelin’s Stairway to Heaven?

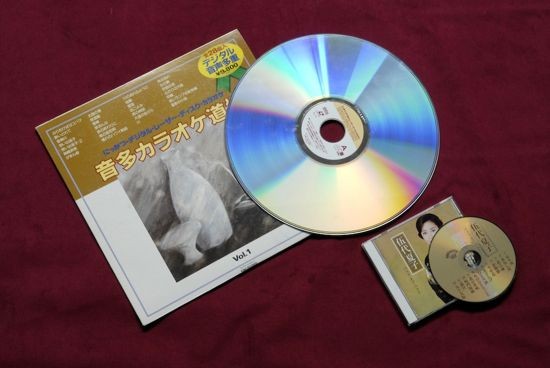

Karaoke, the “empty orchestra,” originally gained popularity in the 1970s as instrumental renditions of popular songs in an eight-track tape format, but underwent a transformation in 1982 with the advent of “karaoke with pictures.” The age of laserdisc karaoke had arrived.

Thirty centimeters in diameter, LP-size laserdiscs were first marketed in 1978 in the United States, but as indicated by the fact that “LaserDisc” is a Pioneer trademark, it was a Japanese firm that drove the development of the technology.

Laserdiscs, which offer better sound and picture quality than even today’s DVDs because they can store audio and video data without compression, battled Victor’s VHD format to achieve market dominance against overwhelming odds (VHD manufacturers numbering 13 to Pioneer’s solo effort for the laserdisc), and went on to nationwide distribution in Japan as both movie and karaoke playback hardware.

Laser karaoke was a magical device that crammed in far more data than anything that had come before, supplying a video to accompany each tune. Tape karaoke required a lyric sheet or book to sing, but the laserdisc system supplied audio and visuals simultaneously, and by overlaying his or her own voice on the video and accompanying music, the singer could plunge completely into the world of the song, playing the starring role in its story.

But the golden age of laser karaoke was short-lived. The arrival of online karaoke in 1992 caused bulky laser machines to vanish from bars virtually overnight. The online format offered a much greater track selection, and was easy to manage. Manufacture of domestic-use laserdiscs limped along for a few more years, before the last maker ceased production in 2007. The players are no longer made either.

These days the term karaoke refers to online karaoke. The videos consist of nature scenes stored on hard disk, unrelated to the actual songs. And though this has taken much of the fun out of singing, strangely nobody seems to find it odd any more.

Laser karaoke, in which sound and visuals were produced for each individual tune, was a cinematic treasure trove of three-minute short films, a visual language that augmented the atmosphere of the song.

Over no more than a decade or so, thousands of short films were produced for thousands of karaoke tunes; the performances of thousands of actors shot at thousands of locations – all now discarded, with no one at all trying to preserve them. A precious record of countless landscapes across the Japanese archipelago, yet no library or film archive shows the slightest interest.

The world of the laser karaoke video is a sea of our lost memories.

All photos ⓒ Kyoichi Tsuzuki.

Kyoichi Tsuzuki is a photographer, writer, editor and independent publisher based in Tokyo. Selected publications include Tokyo Style (1993), Roadside Japan (1996) and Happy Victims (2008). His articles on contemporary culture and lifestyle have been published extensively in magazines including Brutus, Popeye and Weekly SPA!