Five Steps Toward an Eight-Year Manifesto

By Praneet Soi

I

Still from Kumartuli Printer, Notes on Labor Part 1 (2010), slide installation of 80 transparencies with rotary slide projector. Courtesy Praneet Soi.

Still from Kumartuli Printer, Notes on Labor Part 1 (2010), slide installation of 80 transparencies with rotary slide projector. Courtesy Praneet Soi.Standing at the immigration hall at JFK, fatigue was catching up with me as the queue slowly inched its way toward the officers’ cubicles. After the fingerprinting (a grimy electronic finger impression pad) and photo taking (an incongruous construction consisting of a point-and-shoot digital camera attached to a computer) came the questions barked at me by an immigration officer sitting in his box:

“What is your profession, SIR,” he barked.

“An artist,” I replied.

“Artist?”

“Yes,” I replied, “An Artist.”

“What Kind of Artist ?” He shot back.

” What kind of artist?” I asked back, thinking aloud.

“An artist – it’s a secular profession,’” I thought to myself.

“What medium do you use,” he interjected.

I stared at him and swallowed.

“What?” I squawked back, my voice quivering with disbelief.

“SIR,” he shouted back at me, clearly at the end of his tether, “WHAT KIND OF MEDIUM DO YOU USE? Do you PAINT or do you SCULPT?”

A nation implies a demarcated territory that accepts or rejects entry, a citizen body that is subject to its formatted rules. Yet contemporaneity reveals complicated structures of nationality that require careful unpacking. It would be refreshing to think of art as existing outside of this nomenclature. Or parallel to it.

II

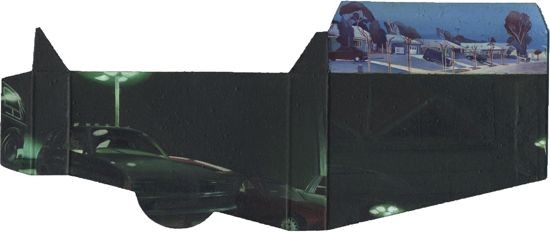

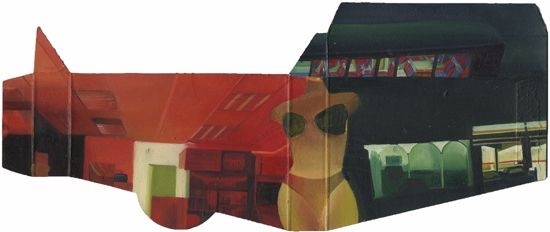

Both: From the series “The California Miniatures – Essays on the Southern California Landscape” (2001), oil, varnish and gouache on unfolded carton, approx 27 x 11 cm. Courtesy Praneet Soi and Cees & Inge de Bruijn Heijn.

During our final semester at the University of California at San Diego, my best friend Kenny – a film editor originally from Austin, Texas – and I were awoken early one morning by the phone ringing. Kenny, usually sensitive to my privacy, thrust open my door and stumbled into the room, saying JP had been on the line, quite frantic, shouting into the mouthpiece about a terrorist attack in New York. He was coming by immediately to pick us up, and we needed to get ourselves to a television.

Kenny and I piled into JP’s car and set off to a friend’s place in Mira Mesa, near the Marine Corps air base in Miramar. All the FM stations were relaying the commentary being broadcast by NPR, a commentary that was amplified in the insulated interior of the car. I looked out the window and noticed, as we waited at a red light just before entering the I-15, a woman in designer gear jog past the zebra crossing ahead of us while pushing an aerodynamic pram in front of her, the monumental freeways of California and the voice of Bob Edward providing a surreal backdrop to this strange moment.

I moved to Europe a half-year later and ended my three-year exile from home by setting up a series of exhibitions and a residency program that would keep me traveling between Kolkata and Amsterdam. Yet this particular image stayed with me over time as a moment when the world changed. And it has stayed with me to date as I continue to negotiate between cultures, dealing with the complicated questions of integration and patriotism that an itinerant life throws up, the incessant calibration required to maintain the relationship between my two homelands, the Netherlands and India.

III

Installation view of the Indian Pavilion at the 54th Venice Biennale, 2011, acrylic paint, charcoal and glass marker on constructed wall, 9 x 5 x 4.5m. Courtesy Praneet Soi and Lalit Kala Akademi, New Delhi.

Installation view of the Indian Pavilion at the 54th Venice Biennale, 2011, acrylic paint, charcoal and glass marker on constructed wall, 9 x 5 x 4.5m. Courtesy Praneet Soi and Lalit Kala Akademi, New Delhi.On the Greyhound on my way from New York to Georgia, the driver was running ahead of schedule. I knew the road, having traveled this way before, and realized at a certain point the driver had taken a different route than the usual. We were no longer on the highway but in a gently rolling rural landscape. Farmland was punctuated ever so often with farmhouses, rickety wooden structures that often had windowpanes that were boarded over. Rotting cars and old trucks stood propped up on bricks with parts missing. Tattered armchairs were placed upon the porticos overlooking the road. It wasn’t completely bucolic; signs of industrial activity – including its waste – pervaded, lending the landscape a faintly melancholic air. I lived and worked in Georgia for almost six months before making my way to California. Remembering my life there, I wonder what might have happened if I hadn’t moved on. If the small town I had inhabited had become my home.

IV

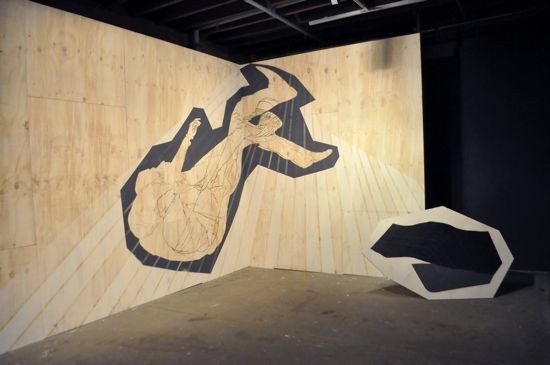

Writing in the Wall (2011), acrylic, charcoal and pencil on wood and plywood, installation view at Artspace, Sydney, 2011. Courtesy Praneet Soi and Artspace.

Writing in the Wall (2011), acrylic, charcoal and pencil on wood and plywood, installation view at Artspace, Sydney, 2011. Courtesy Praneet Soi and Artspace.Many years ago, during the last years of high school in Kolkata, one of my friends, RL, was going through a difficult time, and at a certain moment he disappeared from view. Phone calls to his home were fielded by his parents who, while apologetic, never revealed much, promising that he would call back, which of course he didn’t. I learned from his girlfriend that he was working as an intern at Mother Teresa’s ashram in Kalighat, and, as I hadn’t seen him for many weeks, decided to visit. Once there, however, I decided to enroll. We were the only local interns; the rest were from every corner of the globe, glad to have an opportunity to work for Mother Teresa.

The ashram was essentially a hospice, meant to provide a comfortable resting place for those who would otherwise have died untended on the streets of the city. While some of the inmates were healthy and obviously abusive of the charity they were provided, I saw and tended to people who were quite obviously in desperate need of help.

One day a Japanese intern came running to me saying that he had been trying to drape one of the inmates with a cloth as he slept, but the inmate had woken up and begun to loudly protest, finally flinging away the drape. The Japanese intern couldn’t understand Bengali, so I went along with him to see what the fuss was. On asking, the inmate told me that the Japanese had tried to cover him with a white blanket. He wanted a blue one – the white was used to drape corpses, he explained.

V

Still from the slide installation Okhla Mandi, 80 slides with rotary slide projector. Courtesy Praneet Soi and Rick Hunting Collection.

Still from the slide installation Okhla Mandi, 80 slides with rotary slide projector. Courtesy Praneet Soi and Rick Hunting Collection.I took the subway from Williamsburg into Chinatown, heading to the art supply store to buy some equipment, gouache colors and a few 000 brushes. On the way, I came across a small makeshift table amid the bazaar-like atmosphere of the pavement, around which a group of people were assembled. At the center was a big black guy who was shuffling three opaque glass tumblers. One of them contained a coin and the trick was to spot the tumbler in which the coin was hidden.

An old, toothless Chinese man, a member of this bunch, kept throwing down huge wads of notes and clutching his head in disbelief at his misfortune every time he lost. A black woman stood on the fringe, tentatively putting down a dollar or two. I stood next to her and watched the shuffling, trying to keep an eye on the winning glass. I guessed right a couple of times and started giving her advice as I wasn’t placing any bets myself. She won every time, clutching my arm in delight.

Breaking away from the group, I walked to the closest ATM I could find and pulled out 35 dollars. I had just cleared rent and was down to my last 100 for the month, with food and cigarettes thrown in. I hurried back only to learn that they had packed up as a cop had been seen nearby. Disappointed, I walked into the store, bought my paints and brushes and was returning to the station when I saw them again across the road, almost hidden by the roadside kiosks. I joined them and put down 35 dollars, sure I would double it but losing it immediately. Trying to recover from the shock, I noticed a pair of girls stop to watch the action. “Double your money,” the shuffler called out to the one closest to him, and asked her how much she would like to put down. “A twenty?” she asked, tentatively, pointing to a tumbler while rummaging in her bag for the cash. She brought out a 20-dollar bill, which was deftly plucked from her fingers as no time was wasted in proving her wrong.

That this was a con-job didn’t require much proving. Yet the group had created a system that generated an economy, albeit one that worked only for them. The avant-garde has become one such system. Operating within an insulated environment, it excludes everything outside its frame, creating a scenario whereby it propagates the status quo instead of challenging it or championing heterogeneity.

This is a subject that I have been discussing with friends in Kolkata, Delhi and Mumbai, coming to the realization that an interesting position would be one that operates beside, or just on the outside of this system. One that observes, but doesn’t always feel compelled to enter.

It becomes apparent that a cosmopolitan art community inevitably gravitates toward work that can be comfortably contextualized. It is unfortunately not rare to see work that is firmly entrenched within a particular geography ignored as its complexity does not translate well – work that is simply brushed aside, where enquiry would shed light upon the conditions that shaped the work as the artist attempted, through the act of making it, to perceive his or her environment.

In a complicated art scenario such as India, where we increasingly see individual, institutional and, now, international forces jostle for the power to have something to contribute, it might perhaps be considered important to articulate a manifesto that calls for existing practices to be studied in the light of the culture from which they are produced and so create an infrastructure, not only for them to be read and understood (they are) but also to develop the terrain of research that would allow for an expanded notion of scholarship to come into being.

Work by Praneet Soi is currently on view through November 27 in the Indian Pavilion at the 54th Venice Biennale, “Everyone Agrees: It’s About to Explode,” curated by Ranjit Hoskote, and in a site-specific project at Artspace, Sydney, “Writing in the Wall,” through August 21. Soi also has a forthcoming solo exhibition at Museo Experimental El Eco, Mexico City, and is participating in the forthcoming survey exhibition “Generation in Transition: New Art from India,” at the Zachęta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw.