Overseas territories as cultural resource

East Asia Image of Modern Ages exhibition at the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art

Installation view of East Asia Image of Modern Ages, Toyota Municipal Museum of Art, 2009

Oh Mijung’s new book Abe Kobo no sengo (Abe Kobo’s ‘Post-war’) (Crane), which was published not long ago, is a fascinating read. With his experimental and abstract literary style, Abe Kobo is widely regarded a pioneer who literally cleared the way for the ‘post-post-war’ in post-war Japanese literature, which began with the wartime generation known as the senchuha whose work reflected their experiences of the 15 years of war beginning with the invasion of Manchuria in 1931. However, the author argues that Abe’s literature also unmistakably reflects the different post-war experience of Manchukuo, carefully tracing his early texts in an attempt to show that in this respect Abe’s literature is still ‘post-war’. In fact, it often occurs to me that Abe’s dry literary style and methodology, which are often described as mukokuseki (literally ‘without nationality’), may have reflected the federalist experiment that was Manchukuo, which was colonial yet at the same time based on the fictional doctrine of ‘five races under one union’, as well as the protean territory of Manchukuo itself that made such a reconstructive sensibility (a desert philosophy?) possible.

Come to think of it, for Abe, who at one stage aspired to become a physician, perhaps it was the rootless territory of the ‘dissecting table’ (Lautréamont) that later became the stylistic basis, as it were, of his surrealism. Considered in these terms, Abe’s literature, which always seemed in danger of being reduced to an inferior imitation of Kafka, has a good chance of regaining its true historicity at a different level from the crown of victory of flavorless ‘world literature’ (in other words a contemporary readership). At the same time, however, the author of this present work asserts that Abe’s reputation as a cosmopolitan writer became established around the time in the 1960s when the rapid growth of the Japanese economy reached a peak, which coincided with the elimination of this kind of historicity. Accordingly, what is required now is not to read into Abe’s works the transnational abstractness of someone who has lost their homeland but the ability to perceive indications that these works might in fact be reflections of a different kind of homeland experience.

Come to think of it, at the start of his career, Abe was also among the most closely involved in art of all the members of the post-war literati, having participated in groups such as Okamoto Taro’s Yoru-no-kai and Seiki (which included Ikeda Tatsuo, Katsuragawa Hiroshi, and Teshigawara Hiroshi among others). That being the case, his tendency towards surrealism was probably something that formed through his associations with these groups. That being the case, might it not be possible to reconsider Japanese surrealist art of this period through the medium of the Manchukuo experience of the writer Abe Kobo? By a curious coincidence, it was just after thinking this that I got a chance to go along to the East Asia Image of Modern Ages exhibition held at the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art.

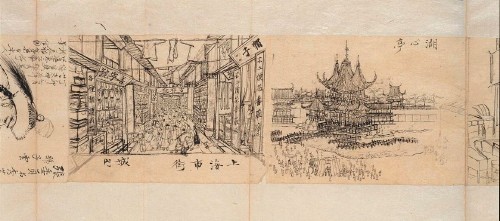

Takahashi Yuichi Shanghai Diary 1867

Sumi on paper, 23 x 18.5cm. Courtesy Tokyo University of The Arts

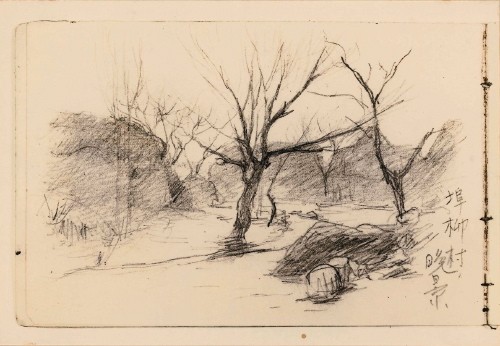

Kuroda Seiki Sketchbook No.14 (The Sino-Japanese War) 1894

Pencil on paper, 12.2 x 18cm. Courtesy Tokyo National Museum

Apparently this is the first exhibition curated by the art critic Amano Kazuo since he quit his post as a professor at Kyoto University of Art and Design and assumed his new post as chief curator at the museum concerned. It’s a truly ambitious exhibition, incorporating a sizable number of pieces that reflect the vigorous research that went into it (and although I won’t go into detail in this column, in this respect it seems to be on a par with the equally magnificent The Coal Mine as Cultural Resource exhibition organized by curator Masaki Motoi and held at around the same time at the Meguro Museum of Art, Tokyo). In fact, works like Takahashi Yuichi’s Shanghai Diary and Kuroda Seiki’s Sketchbook, which hit the eye as soon as one enters the venue, are sufficient as introductions to alert the viewer to the fact that this exhibition aims to reread every aspect of the very history of Japanese modern art by retracing ‘how artists have depicted Asia’. In fact, this exhibition goes on to present works by such artists as Kishida Ryusei, Fujita Tsuguharu, and Inokuma Genichiro to illustrate each of its essential points, as well as presenting works by the likes of Kimura Ihei and Onchi Koshiro with a view to covering the history of photography, and even including towards the end works by the likes of Aida Makoto and Takamine Tadasu. However, this is not simply an attempt to discern the alternative narrative of colonialism behind Japanese modern art. As is clearly illustrated, for example, in the part devoted to the likes of Yasui Sotaro and Umehara Yuzaburo, the important thing is that the very style of these founders of the nation-statist Western-style painting ideology was something that became possible in the overseas territories themselves where they in fact depicted the Chinese mainland. This eventually gave rise to the contention that by way of Japan’s defeat, this style that made its way back to the Japanese homeland (by way of the experience of survival after defeat) formed the departure point for post-war art. In this respect, I tend to think this exhibition sheds light from another angle on the same problem contained within the literature of Abe Kobo outlined at the start of this column.

Installation view of East Asia Image of Modern Ages, Toyota Municipal Museum of Art, 2009

In fact, as Amano also points out, for Japanese modern artists who regarded the experience of studying in the West as the very essence of their egos, the problem of how to transform into oil paintings the Japanese landscape, which was completely different to that of the places where they studied, remained a conundrum that had a lasting effect. The falsity of works from the Meiji period that depict in an Impressionist style country farm laborers as ‘peasants’ invites sniggers from viewers now more than ever (I have actually witnessed such a reaction from a group of high school students at a certain public art museum), although for artists at the time it was something worth pursuing. At times like these, the fresh terrain of the overseas territories, which was far removed from the conundrum of how to depict as ‘Western’ the essentially ‘Japanese’ terrain and people of their homeland, whose colonial nature did away with the need to share the inner world of the people or landscape, and where it was possible to devote oneself singleheartedly the object of their paintings, probably also represented a land of semi-salvation for these artists.

Installation view of East Asia Image of Modern Ages, Toyota Municipal Museum of Art, 2009

In fact, it wasn’t only artists who were able to avoid the difficult issues facing the homeland and become purely methodological in Manchukuo. During the war, when one of the slogans was kichiku beiei (American and British devils), to tolerate modernism of all things was actually one of the privileges able to be enjoyed on the testing ground that was Manchukuo. In architecture, for example, those wishing to combine the state ideology with modern architectural methods in the homeland were forced to make some strange compromises (giving rise to the so-called teikan yoshiki, or Imperial Crown style, in which Japanese-style roofs were planted on top of modern ferroconcrete buildings), whereas in Manchukuo architects like Maekawa Kunio were able to pursue designs that anticipated post-war modernism. In addition, the extent to which the technology accumulated in the overseas territories by the Manchukuo Film Association, upon which Toei was founded, was fed back into the post-war visual entertainment industry is something appreciated by many people today.

Thinking about this now, even taking Manchukuo on its own, the vast area covered by this ‘overseas territories as cultural resource’ is unfathomable. Now that the fleeting and groundless Asia boom is on the wane, the time has come not to exploit colonialist images of Asia but to promote a closer examination of our own ‘inner Asia’.

All photos courtesy Toyota Municipal Museum of Art

East Asia Image of Modern Ages

October 10 – December 27, 2009

Toyota Municipal Museum of Art

Index

2: On the ‘budget screening’ of the cultural administration

1: Where is the contemporary in Ohtake Shinro?