For ‘Shomei Tomatsu: Hues and Textures of Nagasaki’

Part 1: Historical background

So long as photographs are in the final analysis pictures, irrespective of how much the photographer tries to put their own interests to one side, an aesthetic judgment of some kind, or in other words a calculation (including a calculation not to calculate) with respect to things like framing and composition, always creeps in. The contradiction between the inevitable painterliness of photographs and an ethic of presenting things as they are. By treating painterly techniques such as framing and composition as active devices not for the purposes of realizing the artist’s self-expression or photographic aesthetics, but for raising pure and simple photographs of reality to the level of direct manifestations of surreal reality, Henri Cartier-Bresson eliminated this contradiction and brought surrealism and documentary photography together. In other words, the world as it is (= the surreal world) is hidden behind everyday reality, and the photographer must use their photographic skills to reveal it.

Looking at Cartier-Bresson’s Scrapbook(1), one can see how he reconciled the painterliness of photographs and the world as it is. While on the one hand he photographs concrete subjects in a straightforward manner, on the other he fits his subjects into the perfect composition, removing them from the contexts and narratives of their reality so that every photograph is complete in itself. Just as an animal is caught in a trap, the moment flowing everyday reality fits into the composition engineered by Cartier-Bresson, surreal reality manifests itself and the photographer releases the shutter before the image escapes. It was when this concept of images à la sauvette (literally “images on the run,” although the English term “the decisive moment” is widely used), was bestowed on surrealism that the noble path of modernist photography known as documentary photography came into existence.

Shomei Tomatsu, too, took as his starting point surrealism(2). Fitting a familiar reality within a certain painterly composition to reveal its surreal form → a familiar reality divulging its surreal form at the decisive moment when it fits into a certain composition… Following this methodology that constitutes one of the kernels of modernism in photography, Tomatsu made the transition to documentary photography almost as a matter of course. Looking at his early work from the 1950s, one can see how his natural sense of composition enabled him to transform all manner of reality in Japan into an invigorating portfolio of photographs. In fact, his almost instinctive sense of balance remains unchanged to this very day. The balance between the direction of the subject’s gaze and space(3), the tug of war between the perspective convergence lines and the direction of movement of the subjects(4), the balanced dispersal of multiple subjects on a single stage(5), the balance between the tilting and the composition within the frame(6), the counterpoint between multiple subjects(7), and various combinations of these techniques are all employed in the masterful pursuit of the full range of compositional possibilities of black and white photography.

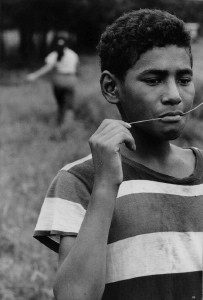

Chewing Gum and Chocolate (3) Kanagawa (1960)

Space is captured behind the subject’s gaze, hinting at the meaning (pensiveness, melancholy, anguish, etc.) behind it. On the other hand, when blank space is captured in front of the subject’s gaze it hints at other things, such as hope for what is about to come, anxiety, or the future.

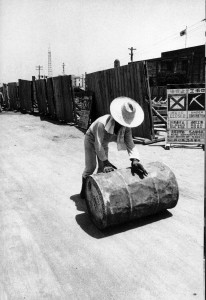

Road Construction (Nagoya) (1958)

The direction of the perspective convergence lines and the direction in which the subject is moving are at odds.

Sit-down (Uchinada, Ishikawa prefecture) (1953)

The way the flagstaffs are dispersed on the stage of straw matting, first two, then another two, then another two, then one, etc. with slight gaps in between.

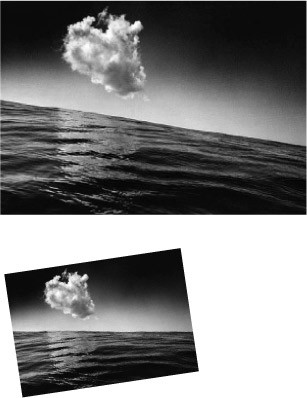

Hateruma-jima (1971)

By adjusting the photograph so that the horizon is level, one can see how the camera has been tilted to the left, applying gravitational pull to the bottom right and creating a balance with the cloud.

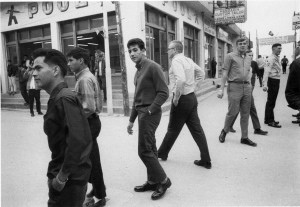

Okinawa (1969)

The counterpoint between the directions in which the men in a line are looking and the directions in which they are walking.

However, what really distinguishes Tomatsu’s photographs from the 1950s, his pre-Nagasaki period so to speak, is that they are actually quite unnatural, contrived photographs. The overly clever photographs based on either conscious or unconscious compositional calculations that almost look as though the photographer had extracted patterns are almost embarrassingly so. The sense of composition completely outweighs the “crude reality.” Why is this so?

When, starting from surrealism, he set out to photograph the real Japan in accordance with this ethic – the exposure of things as they are – Tomatsu was immediately confronted with a contradiction. “The strange reality with which I was suddenly presented I call ‘occupation’.” “Japan as it really existed” was none other than the strange artificial space-time of “occupation” and “under US control.” The contradiction of real = artificial. Of course, it is possible to superimpose this contradiction over the contradiction between the world as it really is and the inevitable painterliness of photographs (which is how Tomatsu’s photographs from the 1950s were possible). However, looking at it another way, one could also say that the surreal reality of post-war Japan was deprived of ‘Japan as it really existed’. The dialectic between photographic technique and realism based on the dualism of the world as it is presented vs. the world as it really is, artificiality vs. nature, is unable to function in these works from the 1950s. At the decisive moment when a familiar reality is captured in a certain painterly composition its plain form is revealed. Or so it ought to be, but its form is a void, and so all we are left with is a painterly composition going nowhere. I find it hard to believe that Tomatsu did not sense this – this shame of seeing his photographs turn into clever, beautiful things. Tomatsu’s black and white photographs are an expression of his essential frustration with modernism in photography. Yet despite all this, Tomatsu himself probably ended up asking himself the following question: If ‘Japan as it really exists’ is absent, where is the decisive moment in the reality of post-war Japan.

The task of documenting in photographs the atomic bombing arose in response to this question. In 1961, 16 years after the moment the atomic bomb exploded over Nagasaki, Tomatsu encounters the city. And this encounter radically changes Tomatsu’s photography. This is because clearly, Nagasaki brought about the collapse of this question itself, and at the same time the collapse of the very thought of realism in photography and of the decisive moment. So what did Nagasaki change? In 11:02 Nagasaki, Tomatsu employs the full range of compositional talents outlined above. Beautiful, clever photographs are burnt in the fire of shame and severely condemned. Unless one questions the meaning of this, and also questions both the process whereby, as Japan moved away from “occupation,” Tomatsu switched over completely to full color photography and the significance of this switchover, one will never understand this exhibition. (To be continued)

“Shomei Tomatsu: Hues and Textures of Nagasaki” was on display at the Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum, from October 3 to November 29, 2009.

1. Henri Cartier-Bresson, Scrapbook. Michel Frizot ed., Thames & Hudson, 2007.

2. See Tomatsu’s early works, for example 1950’s An Ironic Birth and A CruelBride. These and the following examples can be found in Shōmei Tōmatsu 1951-60, Sakuhinsha, 2000 and Aichi Mandala: The Early works of Shomei Tomatsu, Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art and Chunichi Shinbun, 2006.

3. 1956’s Mizukami Elementary School (Tokyo, Fukagawa), 1959’s Third-class Car (Rikuchu-Kawai Station, Iwate Prefecture), 1960’s Chewing Gum and Chocolate (3) Kanagawa, etc.

4. 1952’s Youth (Osu, Nagoya), 1958’s Road Construction (Nagoya), 1960’s Chewing Gum and Chocolate (5) Iwakuni, Yamaguchi Prefecture, etc.

5. 1953’s Sit-down (Uchinada, Ishikawa Prefecture), 1954’s Family Labor (Ceramics Factory, Seto, Aichi Prefecture), 1956’s Barge (Tokyo Bay), etc. This composition is a favorite of Tomatsu’s. See also 1977’s Aharen, Tokashiki-jima and 1978’s Hoshidate, Iriomote-jima. Also Plate 137 in the catalog for this exhibition.

6. 1959’s House, Agar (11), 1971’s Hateruma-jima, 1975’s A Row of Houses with Connected Roofs, Nagoya, etc.

7.1951’s Disabled Veteran (Nagoya), 1954’s Woolen Stomach Band (Tokyo), etc