TO ENTER A VOID

A letter from Hans Ulrich Obrist to Hou Hanru

Absalon – Cellule No. 3 (1991), wood, cardboard, white dispersion paint, neon tube, Perspex, 133 x 161 x 240 cm; 34 x 25 x 179 cm. Courtesy CAPC Musée d’art contemporain, Bordeaux. Installation view at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2010. Photo dreusch.loman.

Dear Hanru,

Thanks so much for your letter and the fascinating words on Zheng Guogu. His land project can be connected to Rirkrit Tiravanija’s “The Land” and many other artist-organized initiatives that propose different models of living. Your letter made me think of Absalon (1964-93), who at around the time when you and I first met proposed his own radical model of living.

I was still living in Switzerland and at the very beginning of my trajectory when I first got to know Absalon. It was in 1991, when I was awarded a Cartier Foundation scholarship. This was just after my first “kitchen show” in my apartment in St Gallen, which had attracted 31 visitors over its three-month duration – not even one visitor a day. Jean de Loisy, who at the time was a curator for the Cartier Foundation, came specially from Paris to see the show, and shortly thereafter invited me to Jouy-en-Josas outside Paris where the Foundation was then based – complete with sculpture park, café and small residences. Not only artists, but also curators, were invited there to do residencies, which was a great idea; the experience was immensely helpful in fostering my curatorial practice. (It seems that today there are not enough residencies of this type for young, emerging curators – a very urgent matter.)

The idea was for the curator to support and be witness to everything that took place there. In keeping with Paul Virilio’s idea of someone who looks over the artist’s shoulder, I was the first “curator in residence.” I drove in my Volvo from St Gallen, armed with a great many books, to spend three months at this artists’ village, where my neighbors to the left were Huang Yong Ping and Shen Yuan, and to the right, Absalon. (This also coincided with the time when you and I started meeting regularly and we can now say it is in the conversations we shared in 1991 that our show “Cities on the Move” had its origins. Following years of incubation it all came together for the 100th anniversary of the Secession in 1996 and then once on track continued to tour and evolve for many years.)

Absalon found his own style very early on, working with a vocabulary of forms he had stripped of function. We talked extensively about this, about the fact that function is actually the shortest phase in the “life” of an object, and yet it is function – determined at a very specific point in time – that dominates the cultural system. Just as culture changes over the course of time, the function of forms evolves too. This change shows, as Absalon repeatedly explained, that an object belonging to the world of utility can only have a limited life – meaning that it can never reach a state of timelessness. After an object quits the utilitarian domain, the sphere of utility, it can only exist on the basis of aesthetic criteria. That idea was profoundly important to Absalon, an idea he formulated very clearly while still in his early 20s.

By 1991-92, he had already conceived this vocabulary. And it was neither the result of appropriation, nor was it related to the notion of the readymade: he strongly mistrusted both. He did not want to appropriate objects he encountered in everyday life, and so he instead created his own forms. He was interested in the idea of potential functionality, not found functionality. He wanted to create objects within which the viewer could discern the potential of a current or a future functionality. Oulipo founder Francoise Le Lionnais also emphasizes the importance of the term “potentiality,” which he prefers to “experimental” – potentiality meaning the attempt to find something that has not yet been done and that could be realized.

Absalon – Left to right: Cellule No. 6 (Prototype) (1992), Cellule No. 3 (Prototype) (1992), Cellule No. 1 (Prototype) (1992), Cellule No. 5 (Prototype) (1992), Cellule No. 2 (Prototype) (1992). Installation view at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, 2010. Photo Uwe Walter.

Even then, Absalon had the fascinating idea of inhabitable sculptures, which the viewer could at least potentially enter, since Absalon himself was living in them. The cells that could not be entered evoked Hans Holbein’s famous painting The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb (1521): of course you cannot actually enter the tomb, but if you are standing in front of it there is a mental, participatory dimension, and in your mind you can move into the image, just as is the case with Absalon’s work. Absalon changed the scale and moved back and forth in that tension between the micro and the macro.

His works are also suggestions for interiors. He felt that most interiors we enter, such as cafés, restaurants or hotels, are intolerable; he could not stand them. This also applied to the room in Hotel Carlton, when in 1993 I invited him, his partner Marie-Ange and 60 other artists to do a hotel exhibition. Absalon played his videos on the TV in the room. And, like all the other artists, he had designed a hotel postcard for the postcard box Walther König and I had created. Absalon asked me if he could have a photo of what he thought was an awful hotel room. Using it he then developed an “intérieur corrigé,” as he called it: he corrected the interior of the hotel room. But he did not limit himself to a particular scale. There were vitrines he filled with maquettes of cities or residential utopias, and at the same time, the notion that the whole thing could be produced on the scale of real cities. Absalon talked about that frequently. I believe that this tension between micro and macro was always present in these interiors.

The idea of white – the most brilliant of colors – is also very interesting. It consists, in all its light, of integral rays. I think the idea of limiting himself to that color came with using white plaster. The question is whether for Absalon, as with Yves Klein and the color blue, the color white was his personified abstraction. I believe it was very important to him from numerous points of view. In Western society, we primarily associate white with freshness, purity and life – “whiter than white” being, for example, a well-known ad slogan for detergent. For Absalon, the symbolism went the other way – owing to his transition from life to death. Edmond Jabès speaks of this in his prose poem “Intimations. The Desert.” He considers white to be a metaphor that is linked to memories of the desert, the sea, images of dunes, of beach and sand. But the circle and the zero also coalesce here, the number zero, the zero as the symbol of emptiness, of forgetting, of death and of God. (Incidentally, in 1989, the magazine DU did an issue entitled “Weiss/White” that included Felix Philipp Ingold’s text “Weiss sein,” exploring aspects of the color white in Oriental and Occidental traditions.) I think at any rate that this was a very important point for Absalon.

Absalon’s entire body of work was a form of resistance. These austere homes that he adapted to his body and that followed his mind were a means of resistance to a society that was keeping him from becoming what he must become. The hermetic and also solipsitic cells that Absalon called his inner mirror and mental space resisted the turbulence of quotidian life. This is an early presentiment of what Paul Chan calls delinking, now an obvious necessity in our digital age. It’s a subjective utopia of a model of living imposed only on himself and not on others, hence his rejection of most revolutionary architectural utopias.

Your example of Brazilian pioneers in your letter also made me think of resistance. Jean-François Lyotard, who after venturing into the world of exhibitions with his groundbreaking show “Les Immateriaux,” also had other unrealized projects on the topic of resistance. These different forms of resistance to our age of communication also bring us to the visionary Italian artist Emilio Prini, and his journey without compromise.

Since the late 1960s, Emilio Prini has exerted a very strong influence on artists, critics and curators, yet he nonetheless remains an enigmatic figure in the pantheon of Arte Povera and early conceptual art practices. This is perhaps due to the fact that, more so than many other artists over the years, Prini has worked through the radical implications of dematerialization, keeping his involvement in exhibitions to a minimum in an apparent fulfilment of Duchamp’s prediction that “the great artist of tomorrow will go underground.” Indeed, building on Duchamp’s own seeming withdrawal from art practice, Prini stopped cultivating relationships with the broader art world after 1971; that is, after the end of an initial intense period of production that saw him participate in almost every founding or constituent exhibition of Arte Povera, as well as landmark shows like Kynaston McShine’s “Information,” Harald Szeemann’s “When Attitudes Become Form” and Wim Beeren and Edy de Wilde’s “Op Losse Schroeven”, which opened in Amsterdam one month before Szeemann’s show, and for which Prini undertook a legendary train journey.

Prini’s career has been marked by a consequent resistance to the overexposure of the art world; as he once stated, “I don’t create if it is possible.” The most radical gesture, he suggests, is simply to refuse to fulfil the demands of the art world for merchandisable product, to refuse to play a part in the reproduction of the market. He regards the only existent catalogue on his work, published on the occasion of a 1995 Strasbourg exhibition entitled “Fermi in Dogana,” as problematic, and has resisted many other attempts at publications.

Since I began meeting with Prini regularly on my visits to Rome in the 1990s, I have closely followed the trajectory of his practice, from Documenta X in 1997, to shows in Frankfurt, Berlin and at the Villa Medici in Rome, where Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Laurence Bossé and I invited Prini to measure the space. It is clear from these shows that Prini has never repeated an idea, that his practice is the opposite of routine, and that every exhibition he does is an invention. Prini resists capitalizing on these inventions, and refuses to turn his ideas into a production line of artworks, to spin out an endless series of recognizable objects. There is no “Prini brand.” And though it might at first glance appear that Prini has not been a prolific artist, in fact his practice has been marked by a remarkable succession of truly original ideas, of genuine artistic inventions. In any case, the relatively long gaps between these inventions – Prini’s charged moments of pauses, intervals and silences – are also very interesting, and his resistance to the commodification of the art object and to historicization, and especially his emphasis on the temporality and transience of exhibitions as artistic encounters, has clearly been of huge importance to some of the most exciting younger artists to have emerged during his time.

It has also been a key inspiration for my own efforts to consider, emphasize and extend the priority of time over space in the production of exhibitions, especially in my “Do It” project of repeatable instructions and recipes initiated with Christian Boltanski and Bertrand Lavier, and “Il Tempo del Postino,” which I curated with Philippe Parreno for the Manchester International Festival and which toured to the Theater Basel with the support of Art Basel and the Beyeler Foundation.

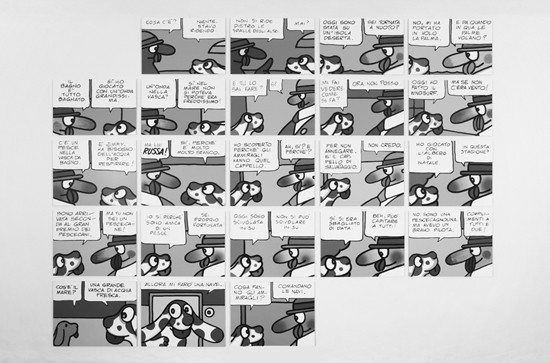

Emilio Prini – La Pimpa il Vuoto (2008). Installation at Galleria Giorgio Persano, Turin.

Despite my prior familiarity with Prini’s work, his recent exhibition “La Pimpa il Vuoto” (Pimpa, the void) at Galleria Giorgio Persano in Turin during the autumn of 2008 was a revelation. For this show, Prini appropriated a series of still frames from the legendary Italian children’s cartoon Pimpa, created by Francesco Tullio Altan, and instructed that these uniformly scaled, enlarged images be installed at eye level along the otherwise bare white walls of the empty gallery. Appropriation is not the correct word to describe Prini’s operation here, however, since, in opposition to the usual process of artistic appropriation, whereby elements of the appropriated original are amplified, exaggerated, enlarged or subjected to a subversion of some sort, where the slightest formal changes unlock the most divergent of readings, Prini’s “Pimpa” undergoes a strict and highly economical subtraction. No new meaning is offered. Even in Situationist or Situationist-derived acts of détournement, these parodic and ironic aspects are mobilized towards the production of some critical excess. Subversion is only subversion because, in some sense, it exceeds in significance that which is subverted. Subversion is, in essence, excessive. But here, as Prini revealed to me in our recent interview in Rome – our first in about 10 years – “People don’t see [the gallery] as empty, but it is empty. . .cartoons mean nothing as art; Altan’s cartoons, as art, do not exist.”

“La Pimpa il Vuoto” is an artistic paradox, an act of addition in order to mark a subtraction. In effect, Prini’s Turin work is the opposite of our standard collective myths of artistic alchemy: he turns something into nothing. The title of the exhibition inevitably invites associations with the great master of the void, Yves Klein, and Prini has told me that his intention with the work was to further develop and surpass Klein, who died prematurely. With Altan’s cartoon frames on the gallery walls, even the spiritual pregnancy of Klein’s loaded metaphysical gestures is erased. The spiritual is undercut by the empty thereness of the images. We are left with nothing, but only because something is unquestionably there. The show almost went untitled, but after many months of deliberation, Prini and Persano settled on “La Pimpa il Vuoto,” in order, perhaps, to both emphasize Prini’s historical engagement with Klein as well as to prepare visitors for the profound and unsettling emptiness at the heart of the work.

Emilio Prini – La Pimpa il Vuoto (2008).

How does Prini subtract in this work? How are the elements arranged so as to effect their own cancellation? Most obviously, all traces of color have been removed from Altan’s cartoon images, and we must not forget that a bold, almost overwhelming use of color is one of the most memorable aspects of the Pimpa cartoon. Also, the individual frames differ from one another to only the slightest degree – engagement with the work begins as a matter of attending to the slightest differences amid the repetition. In every frame, the titular dog, Pimpa, appears in profile, invariably staring at his master Armando, who returns the gaze. Prini’s general pessimism is here underscored by humor: perhaps it has always been easier for humans to talk to dogs than to talk to each other? Perhaps this even remains the case today, despite the opportunities that virtual exchange on the Web supposedly present for avoiding the awkwardness and uncertainty of face-to-face interaction? Nevertheless, the exchanges here between Pimpa and Armando are unfathomable – Pimpa: “Today I windsurfed”; Armando: “But there was no wind.” Action, undercut by absence. Empty ciphers of conversational exchange above two empty ciphers of character. Speech bubbles appear at the top of each frame, dominating each panel but nevertheless given over to nothingness. Prini even goes as far as to say that “La Pimpa il Vuoto” “is not really a ‘work’ of mine – it’s something artistic that I like.”

However, if viewers here create the work, it does not finally belong to them. Instead, it disappears. Like the architectural proposals of the great visionary Cedric Price, whose slow-burning but profound influence on a younger generation of architects and thinkers is comparable to Prini’s in the field of art, the work emphasizes its own transience, harnessing uncertainty and conscious incompleteness. There is a potentiality in Prini’s practice, but it exists at the edges, rather than at the center, of the work itself. It exists at the point where Prini’s production once again becomes dormant, at the point where it returns to, or rather re-traces, the possibilities of silence on the margins of the artistic field, where all that has been revealed in the artworks themselves is finally yet more silence. The transience of “La Pimpa il Vuoto,” its promise to disappear without having first fully revealed itself to us, is suggested by an explanation of sorts that Prini gave to me: “It’s like putting make-up on the emptiness of the gallery.”

It is now almost five years, dear Hanru, that our letter exchange for ART iT has continued, and yet I still feel it has only just begun. Maybe it’s a good moment to think about gathering all letters we have written so far in a book and then starting again. As says Lawrence Weiner, books do furnish a room.

Ever yours,

Hans Ulrich

A retrospective of Absalon‘s work is currently on view until February 20 at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin.

Archive

Curators on the Move 1-14