“Takehisa Kosugi 2022” and Kiyoshi Izumi’s SOMA

Scene from “Takehisa Kosugi 2022” (Hall Egg Farm, Saitama, October 15, 2022). GC (left) and Kiyoshi Izumi (right) performing Takehisa Kosugi’s South, e.v. (1999). Photo: Kiyotoshi Takashima, courtesy HEAR.

Takehisa Kosugi may be dead, but Takehisa Kosugi’s music will live on.

What does it mean to perform Takehisa Kosugi?

Kosugi left behind numerous notes, including instructions for his works and diagrams of the equipment he used.

His extremely simple words and drawings are full of riddles on account of their simplicity.

Through the act of performance, music constantly brings new discoveries.

We are now in an age of discovering a new Kosugi,

And what was once Takehisa Kosugi’s music will in future become ours.—Yukio Fujimoto (1)

While reading Shinji Aoyama’s Takaragaike no shizumanu kame II: aru eiga sakka no nikki 2020-2022—mata wa, ikanishite watashi wa sake wo yame, mattona yosei wo tsuranukitsutsuaruka (The unsinkable turtles of Takaragaike: diary of a filmmaker 2020-2022—or, how I gave up drinking and am going straight for the rest of my life) in preparation for writing a book review for a certain newspaper, I noticed that not only are there turtles in the book’s title, but there is also a turtle logo in the middle of the back cover. Upon looking at this logo close up, I was astonished at how realistic it was, and as a monologue continued in my mind covering such topics as how something so realistic could no longer be called a logo, I thought for some time about turtles. However, I do not have a strong connection with turtles. A long time ago I kept two turtles at the request of my son, but after leaving them on the veranda so that they could bathe in the sun or something, I discovered the next morning that both had disappeared. The edges of the case they were in were too tall to climb over, so perhaps they were eaten by a crow or something. The poor things.

Such is the full extent of my connection with turtles, though I do have quite a few acquaintances with close ties to the animals. Which is why I recalled the tortoise kept in the home of the late Kiyoshi Awazu, which was entrusted to him by Ryo Koike of the Taj Mahal Travelers. Its name was Maranda. I have written about this turtle previously in another essay,(2) but several years ago, in 2019 in fact, which is to say before the COVID-19 pandemic, when I went to see this animal, it had only just woken from hibernation and begun to move around slowly. Having looked up the date of this visit, I remember that I deliberately chose April 1, 2019, April Fool’s Day, and the date of the announcement of the name of the new imperial era. It is still February now, so no doubt Maranda will be in hibernation for some time to come. Apparently Maranda was brought back to Japan after being picked up in a city in Iran near the border with Turkey when the Taj Mahal Travelers were on their way back home after crossing Eurasia. I am not sure of its age, but it must be well over 50 years old. The fact that turtles have long lifespans is well known, so much so that it is part of superstition, as indicated by the Japanese proverb, “Cranes live for 1000 years, turtles for 10,000 years,” but thinking about this reminded me that Aoyama, Awazu and Kosugi are all dead. Even I may not outlive Maranda. This goes to show that thinking about turtles involves thinking about the shortness of life. In which case it might not be such a good idea to distance myself from turtles by stating that “I do not have a strong connection with turtles.”

Speaking of remembering the dead, on October 15, 2022, the concert “Takehisa Kosugi 2022” (planning: Yukio Fujimoto) was held at Hall Egg Farm in Fukaya, Saitama.(3) Due to the pandemic, it was the first time in three years the event was staged, the previous occasion being “Takehisa Kosugi 2019” held at the same venue following Kosugi’s death in 2018. I have also written about “Takehisa Kosugi 2019” (which was also staged at 360 [Jingumae] and Uplink Shibuya) in another essay,(4) but Kosugi’s activities during his lifetime were fundamentally different from the creation of so-called normal artworks. Because they were part of a very process in which everything was continually changing, the situation today is essentially different from one in which an artist has died and left only their artworks behind. Of course, because Kosugi was without exception involved in the process on each occasion, just as with one-off performances or dances, it may seem that his works can never be recovered after his death. But in Kosugi’s case, like Maranda, the turtle he left behind, I sense that irrespective of whether the artist is still alive or not, the echoes of the actions he began to draw as a single line will carry on in some form or another even after his death, and are continuing to be extended even today.

Scene from “Takehisa Kosugi 2022” (Hall Egg Farm, Saitama, October 15, 2022). Izumi Kiyoshi performing Takehisa Kosugi’s Spectra (1989). Photo: Kiyotoshi Takashima, courtesy HEAR.

Scene from “Takehisa Kosugi 2022” (Hall Egg Farm, Saitama. Iryoku (left) and Kiyoshi Izumi (right) performing Takehisa Kosugi’s Organic Music (1962). Photo: Kiyotoshi Takashima, courtesy HEAR.

In this regard, no works by Kosugi exist to which the words final or posthumous works can be applied. It even feels as if there is not much difference between the time when he was still alive and now, when he has departed this world. Of course, even after an artist dies his works still remain. In this sense, like turtles, artworks outlive humans by a long time. But in the case of Kosugi, I feel it is slightly different. To put it in extreme terms, there is something about Kosugi’s works that, through various contrivances on the part of the artist, appears to expose aspects of the world that existed before the artist was born, and so regardless of whether Kosugi is alive or not, the world that appears temporarily before our eyes through his works is always fresh and new. The concept of retrospectiveness is not applicable to this. And if retrospectiveness is not applicable, then naturally there can be no final or posthumous works.

Perhaps the opposite of this is On Kawara. As if an absentee from the time he was alive, Kawara did not appear in public, continually sending out only signs of life from this position of absence. In this sense, it was as if even after the artist died there were no particular changes in the circumstances surrounding him. But to put it another way, perhaps we can say that by consistently pretending to be an absentee from the time he was alive, in fact a clear line can be drawn between the times before and after his actual death. However, Kosugi casually appeared in front of people from the time he was still alive, and the turmoil of his life and events since his death are ambiguously intermixed without him receding from view in any way. The chief cause of this is probably that most of Kosugi’s works did not physically exist. Of course, they are not completely intangible, but the materials Kosugi dealt with were always restricted to what was the minimum required in order to draw out the process that arose on each occasion. Rather than materials/works, they are at most devices. And because of this, if one wants to resume them they can be resumed; in other words, I think they are better interpreted as hidden processes without beginning or end that are interrupted intermittently for long periods. If so, then even now that Kosugi is dead, as long as there are people interested in resuming these processes, and as long as it is possible to provide the opportunities, then the processes that Kosugi discovered can be resumed again at any time and at any place.

Looked at a different way, these unique characteristics of Kosugi’s works tend to make realizing retrospectives difficult in the sense touched on above. If there are not even any posthumous works, and all that exists are interruptions in processes in which it is possible to become involved, then this is not surprising. It may be that the only kind of thing that can be realized is something like “Takehisa Kosugi 2019” and “Takehisa Kosugi 2022,” where on each occasion Takehisa Kosugi’s present is unraveled from its interruption and resumed. However, while these may not be straightforward, comprehensive retrospectives, I get the sense that they are far more appropriate for an artist like Takehisa Kosugi.

Scene from “Takehisa Kosugi 2022” (Hall Egg Farm, Saitama. (From left to right) Yuji Takahashi, CG, Yukio Fujimoto, Kiyoshi Izumi performing Takehisa Kosugi’s Distance for Piano (1965). Photo: Kiyotoshi Takashima, courtesy HEAR.

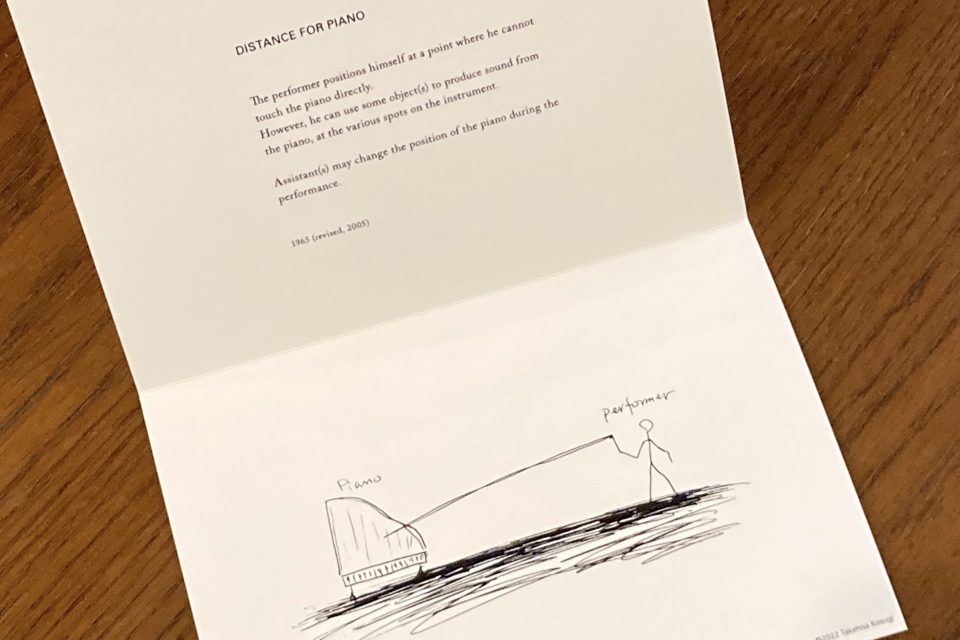

Card handed out at “Takehisa Kosugi 2022” and “Kosugi Takehisa: Oto no sekai – atarashi natsu 1996” [Takehisa Kosugi: The World of Sound – A New Summer 1996] (360° [Jingumae], Tokyo), featuring instructions and drawing for Distance for Piano

Card handed out at “Takehisa Kosugi 2022” and “Kosugi Takehisa: Oto no sekai – atarashi natsu 1996” [Takehisa Kosugi: The World of Sound – A New Summer 1996] (360° [Jingumae], Tokyo), featuring instructions and drawing for Distance for Piano

I have gone on at length about Kosugi, but in fact what I want to discuss this time is not Kosugi alone. I also want to discuss Kiyoshi Izumi, an artist who played an important role in both “Takehisa Kosugi 2019” and “Takehisa Kosugi 2022,” in which sense he has continued to resume Kosugi’s work during its interruption whenever possible. Izumi started out as a painter, but because he has a background in music, he has also continually been active as a musician and a performer. Having at one point gained Kosugi’s trust, he later became an indispensable co-star in Kosugi’s activities. However, in order to discuss Izumi, I need to add another introduction, this one concerning scent.

By scent, in short I mean the sense of smell, and while it may not be as easy to understand as the other senses, such as sight and hearing, in our daily lives it has crucial significance. Perhaps such things do not need to be reiterated. But it really is true. If we transitioned to a world without scents, it would be as if the world had suddenly lost all color. It could be that I am using such a metaphor because I respond more alertly to aromas and smells than other people. Moreover, there is a subjective aspect to the role the sense of smell plays in people’s own lives, and no objective way to measure its extent. However, my family often find me useful in guessing whether food in the refrigerator can still be eaten regardless of whether it is past its use-by date, so to that extent it would seem I am I am sensitive to aromas and smells. It is often said that food tastes best when it is starting to rot, but leaving aside the truth of this matter, there is certainly a difference, albeit it an extremely subtle one, between the smell of food that is on the very edge of being safe to eat and that of food that is very similar but best avoided on this occasion. Or rather, though this difference exists, it cannot be expressed numerically, and so despite the fact that my judgement is based purely on experience, I have never doubted it. If I were to add one thing, it would be that because there is a subtle difference in my judgment depending on whether I am eating something myself or whether my family is eating it, it is even more difficult to generalize. But based on my experience, as far as the sense of smell is concerned, such a barometer certainly exists.

Notice that while I said I wanted to talk about the sense of smell, I have gradually been shifting the conversation in the direction of food. However, and this is something that also applies to drink and in particular alcoholic beverages, for me at least, most of the enjoyment of food is derived from its aroma. As for the rest, a great deal is derived from the mouthfeel (ie, sense of touch) after eating (firmness, feel on the tongue, consistency when chewed, feeling going down the throat, etc.). Appearance comes much further down the list, and in truth for me taste does not account for very much at all as far as enjoying food is concerned. In fact, our sense of taste is extremely crude and simple to the extent that we can only recognize sweetness, saltiness, bitterness, sourness, umami and so on. And even though there are also variations derived from combinations of these, our sense of taste is no match at all for our ability to recognize gradations or difficult-to-describe subtleties in aromas. As well, aromas are not only things that can be acquired from the outside through our noses, for aromas that pass through our nasal cavities from our mouths while we are eating are also extremely important. There are also aromas that linger in our noses from our mouths after we have swallowed, and in the case of whisky, for example, one could actually say these accounts for almost everything.

What I want to say is that, to the extent that I have written about it in detail here, I am captivated by aromas. So when someone wearing strong perfume sits next to me in a sushi restaurant, for example, I find it extremely annoying. I am also keenly aware of the aromas and smells of individual eateries. I am not saying, however, that the more upscale the restaurant, the more thoroughly it is cleaned and the more hygienic it smells. I am turned off by eateries that use artificial fragrances, and it is not necessarily only Japanese-style bars that have disparate and annoying smells. In short, aromas are like the atmosphere of a particular establishment. So each establishment gives off aromas or smells that are similar to the type of food or drink it serves. Perhaps this is easier to understand if we compare it to the different fermented rice bran beds used for pickling in people’s homes. In the same way, the pickled vegetables served at restaurants that are regarded as upscale do not necessarily have pleasant aromas.

Anyway, for the above reasons, when I view art, too, a lot of my sentiments are actually directed at aromas and smells. A lot of people are probably aware of this, but each art museum or gallery has a peculiar smell that stubbornly hangs in the air. This is completely unrelated to how thoroughly maintenance is carried out, and is perhaps best explained as an inherent characteristic of the exhibition space. In this sense, art museums and galleries are already thoroughly site specific from the time each one of them is established. Of course, to the extent that they are made from certain materials, it is common for artworks themselves to give off faint smells, and there are artists like Noboru Takayama (who recently died) whose works give off a strong scent of coal tar that has become a distinguishing feature of great significance to the pieces concerned. Be that as it may, in actuality, art and scents or smells are inseparable. However, without raising again the matter of “white cubes,” we have completely forgotten the important position scent has in the art experience. In fact, because too much emphasis is placed on the fact that displays in white cubes, which have long been regarded as a universal (ie, international) format, are a system that specializes in the sense of sight, an unnatural purification that transparently eliminates the scents or smells actually emitted by a place is matter-of-factly taken for granted, or rather it is forgotten.

On that subject, things such as the kind of smell one encounters upon arriving in the terminal at such and such an airport are often brought up in jocular chat. In Japan, there are several variations, including soy sauce or miso, but there seems to be a consensus of opinion that the most powerful smell is curry. Though I have not done any research, and therefore cannot be certain, because it is the perfect example of a dish loved by everyone that has spread throughout the whole of Japan more widely than ordinary Japanese cuisine, for the time being I think we can say that there are no food and beverage facilities where people gather that do not have curry on the menu. This is probably also the case at art museums, and while I do not know how many art museums do not offer curry, I presume they are all carefully designed so that the smell of curry in the restaurants does not reach the gallery spaces, since it goes without saying that if such smells did reach the noses of visitors, the viewing experience would be completely different.

Rirkrit Tiravanija – Untitled (Free)) at 303 Gallery, New York, 1992.

Rirkrit Tiravanija – Untitled (Free)) at 303 Gallery, New York, 1992.

©︎ Rirkrit Tiravanija, courtesy Gladstone Gallery and Gallery Side 2.

Incidentally, the first time I experienced a strong curry smell in an art exhibition space was more then 30 years ago. In 1992 I spent around half a month in New York, and during a visit to 303 Gallery, which then occupied part of a multitenant building in SoHo, I witnessed Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija serve a Thai curry (Untitled (Free)). This installation was part of a series that began in 1990 with Untitled (pad thai), in which the artist served the popular Thai dish pad thai in the same gallery, and while food and drink are often served to visitors at private galleries of this sort on the first day of an exhibition to celebrate its opening, Tiravanija’s case is different in that the serving of food itself is part of the work.

Such ventures have historical precedents, including Gordon Matta-Clark’s Food (1972), in which a group of artists worked together to create a space that served food. They have also been critiqued with reference to Nicolas Bourriaud’s concept of relational aesthetics, but in essence they do not go beyond the bounds of an ongoing event. In fact, the appeal of food is indispensable to the program format at the art festivals so popular all over Japan today, and is a major foundation that strongly connects the local “site” and the art experience of visitors, and drives such events from a tourism standpoint. In this sense, far from being something extremely unusual, in terms of today’s art, alongside special menus offered at eating and drinking facilities at art museums to tie in with particular exhibitions, such ventures have become an extremely common sight.

Curry served at SOMA (Osaka). Photo courtesy SOMA.

However, a clear line can be drawn between Izumi’s activities, which deliver mainly food and aroma through eating drinking, and activities like those mentioned above that can be defined broadly as “events.” Izumi’s “artwork” (I use this term deliberately) is a spice curry restaurant that completely takes the form of an eatery, and in most cases the people who visit it are completely unaware that it is an artwork by Izumi. Or rather, while there are probably some people who visit the store with this in mind, as demonstrated by the fact that it was featured on the popular TV show Jonetsu tairiku (Passionate Continent), the spice curry restaurant Izumi runs is better known as a popular eatery that stands out above the rest even in Osaka, which is known as the birthplace of spice curry in Japan and where numerous restaurants compete ruthlessly for customers day and night. Accordingly, long lines form before opening time during the day and it is far from unusual for the food to sell out completely before closing time. Given these circumstances, while they say something about the art experience via spice art, and while they also say something about the connections among people in exhibition facilities or the mingling with others in the context of artworks and art, more importantly, amid our rapidly changing society, Izumi’s works are building connections on a daily basis and at a level far higher than art with unknown visitors that rush in like surging waves. In this sense, we can think of Izumi’s activities as a perfect example of “ART/DOMESTIC (Temperature of the Time)” (Takashi Azumaya) or “ART/BEYOND DOMESTIC” (Yutaro Midorikawa), which have recently been used as key concepts in this column.

Izumi calls his restaurant SOMA, but the thing I rate SOMA for above all else is Izumi’s approach of regarding everything, from the daily mixing of countless spices, his research into the compatibility of these with various ingredients, his ongoing study of the aromas produced by this spice blend and the purchasing of supplies to the running of the restaurant, as an artwork. This is fundamentally different from offering food as an artwork temporarily in a fixed location. Furthermore, at SOMA, together with the aroma of the spices, the plants, lacquerware, tables and chairs, Izumi’s own sketches and paintings, and the music playing in the restaurant all stimulate the senses of the people who gather there, continually giving rise to something that cannot be experienced unless one is present, which, to follow the example of Kosugi, is none other than the invisible process itself.

Views of the SOMA interior. Photos courtesy: SOMA

Of these activities, the way the subtle changes in the electric current produced by the leafy plants placed around the restaurant are expressed by connecting them to an analog synthesizer and playing the changes in sound that arise through speakers perhaps most clearly continues the tradition of Kosugi’s art of invisible processes. In a similar vein, the combination of spices in the curry Izumi serves came about as a result of Izumi keenly studying the subject after hearing from Kosugi that pianist David Tudor (famous for a long time as the pianist who “performed” in the premiere of John Cage’s 4’33”, and the creator of live electronics works for Merce Cunningham through the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, for whom Kosugi served as a resident musician/composer) was obsessed with a particular combination of spices (Tudor/Izumi’s spices versus Cage’s mushrooms—spores?). In other words, without knowing it, visitors to SOMA are consuming (experiencing, or appreciating?) a formless process in the shape of a new recipe derived from the existence of a combination of spices passed from David Tudor to Takehisa Kosugi. However, in terms of “consuming,” the spice curry served at SOMA exerts influence not only on aroma, taste, mouthfeel and throat-feel, but through the direct stimulation that is the spices, also on later processes, which is to say the esophagus, the stomach, one’s feeling after eating, digestion, the absorption process (the intestines), excretion, and even changes in one’s physical condition and feelings for several days after eating. And all of these changes and the totality of these bodily conditions are an integral part of SOMA.

Finally, there is a reason why I have considered Izumi’s works by way of his investigation of aroma and his long-term running of a restaurant, and that is because I also wanted to consider the kinds of changes that will inevitably be brought about in terms of the art experience as a result of studies of the business form of eating and drinking, which has been hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic, and the situation in which our sense of smell has been restricted on a daily basis by masks. As outlined above, because I regard myself as relatively sensitive to aromas and smells, when I encounter art while wearing a mask, I feel that something is missing compared to how it used to be as an experience. Of course, at facilities that have an unpleasant smell, masks actually provide a benefit in that they can block its effect, but as someone who has accepted the smell of such places as part of the site-specific experience, I cannot help feeling that the experience is different from what it was originally. Whether indoors or outdoors, I am in agreement with the wearing of masks itself, and do not feel much discomfort with a mask on. The unfortunate thing is that wearing a mask prevents me from enjoying the viewing experience accompanied by aromas and smells.

On that subject, having kept a dog for the last two years or so, I am used to taking it for walks every morning and evening, sometimes late at night, and this has reminded me of how important smells are to animals. When a dog sees a utility pole it rushes towards it and eagerly sniffs at its base until it is satisfied. One could say this is a matter of poor training, but for animals such as dogs whose sense of smell has developed to the extent that it far exceeds that of humans, the world is brimming with aromas and smells, which is how they accurately grasp their environment. In this sense, they undoubtedly have perception and awareness that are completely different to humans, who tend to construct an image of the world based on our sense of sight and at the very most our sense of hearing. For dogs, aromas and smells not only clearly convey to them the circumstances of a place at one time, but they also function like a mail facility for the forwarding of precious time enabling them to learn what dogs have passed that place and the kinds of messages they have left behind. What to our eyes looks like a plain utility pole is in fact something filled with completely different memories and backgrounds. There is something shameful about this being completely suppressed by human training.

The symptoms and aftereffects of COVID-19 include the loss of the senses of smell and taste, which for me (though not only me) would be quite terrible. It would probably turn the art experience, the visual experience included, into something completely different than before. According to Izumi, he came up with the idea of setting up SOMA after drastically rethinking interpersonal communication in the wake of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. Today, however, in a world where a mysterious virus whose cases include sensory disturbance is still rampant as an epidemic, Izumi’s SOMA seems to have even greater meaning than before. And as suggested in the statement by Yukio Fujimoto quoted at the beginning of this column, Izumi’s SOMA is proof that even though Takehisa Kosugi may be dead, his music will live on, and that after his death, it will continue to be the most magnanimous response to the question “What does it mean to perform Takehisa Kosugi?” and to the fact that “We are now in an age of discovering a new Kosugi, and what was once Takehisa Kosugi’s music will in future become ours.”

1. “Takehisa Kosugi 2022” (event information; in Japanese), Hall Egg Farm website.

2. Noi Sawaragi, “Kosugi Takehisa to Maranda to iu na no kame, sono owari no nai tabi to yume” [Takehisa Kosugi and the turtle named Maranda: Endless journey and dreams], Artscape (May 15, 2019).

3. Held in conjunction with the exhibition “Takehisa Kosugi: The World of Sound – A New Summer 1996” staged at 360° [Jingumae] (October 14–November 5, 2022).

4. Noi Sawaragi, “Kosugi Takehisa no ashiato o tadoru ‘ongaku no pikunikku'” [Following in the footsteps of Takehisa Kosugi “Music Picnic”], Bijutsu techo (December 2019).

Editorial note: “Experimental Spices,” a talk session by Kiyoshi Izumi and Naohiro Ukawa, was held in conjunction with the International Students Creative Award (ISCA) 2022 (on January 21, 2022), and at “Curry LIVE @SpringX” held on the same day, Izumi wore a sensor on his body and cooked curry, during which the subtle voltage generated by the movement of his muscles while cooking was converted into sound.