Matter-of-fact supernaturalism

View of “Sato Masaharu: Trace – absence of presence/presence of absence” (2021) at the Contemporary Art Gallery, Art Tower Mito.

View of “Sato Masaharu: Trace – absence of presence/presence of absence” (2021) at the Contemporary Art Gallery, Art Tower Mito.Photo Naruki Oshima, courtesy Contemporary Art Gallery, Art Tower Mito.

Viewing it again today, it is as if the 2019 film About Endlessness by top Scandinavian film director Roy Andersson anticipates the species-level transformation of our way of life that occurred shortly after the movie’s release upon the spread of the novel coronavirus.

While they do not actually wear masks, the people are taciturn and expressionless, their faces drained of blood, somehow doll-like; they keep their distance from each other indoors, and walk around with heavy steps outdoors. Chilly gazes are directed at frolicking youngsters, and from the outset no one trusts the strangers who sit next to them on public transport. The individual scenes are filmed on elaborate sets made to look exactly like the real world, and the cameras shoot from fixed angles, following (or, in the sense touched on below, “tracing”) in an almost hard-headed way with no elucidation the movements of these people.

Stills from About Endlessness (2019) directed by Roy Andersson. Images courtesy TC Entertainment.

Stills from About Endlessness (2019) directed by Roy Andersson. Images courtesy TC Entertainment.

The effect, rather than a movie in which the whole follows a coherent story, is more like a series of paintings in which the individual scenes are depicted in the same style (with the minimum amount of movement).

This sense of looking like a painting rather than a movie is no accident. In filming About Endlessness, Andersson was inspired by New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit), an art movement that arose in Germany in the early 20th century, and in particular the movement’s paintings, mentioning in interviews the name Otto Dix. More precisely, it might be more appropriate to say that with About Endlessness, Andersson was trying to turn film into painting using the techniques of New Objectivity. (1)

New Objectivity is a key term that always comes up in discussions of early 20th-century art history. But compared to the movements that immediately preceded it such as Dada, Surrealism and Expressionism, it is rather lacking in concreteness, making it difficult to get a clear picture of. This was certainly true in my case, and it is no exaggeration to say that I was finally able to understand New Objectivist painting through watching Andersson’s film.

Karl Blossfeldt – Acanthus mollis (1928).

Karl Blossfeldt – Acanthus mollis (1928).

On célèbre les 130 ans de la naissance d’Otto Dix en compagnie de Sylvia von Harden ! 🍸

Dans ce portrait mythique, c’est tout le Berlin des années 1920 qu’Otto Dix parvient à saisir.

Pour en savoir plus sur l’œuvre 👉 https://t.co/lUfGJrhFrC pic.twitter.com/536aCEljCj— Centre Pompidou (@CentrePompidou) December 2, 2021

Otto Dix – Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden (1926).

A tweet from the Centre Pompidou, where the work is held, on December 2, 2021, the 130th anniversary of Dix’s birth.

But the reason I have expressly brought up the term New Objectivity here is not because I want to talk about Roy Andersson again.

Previously, in another series, not long after the Covid-19 pandemic had spread worldwide, I put forward the theory that the so-called “Spanish flu” pandemic (Spain, however, no longer thought to have been the source) might have cast a heavy shadow over the conventional thinking that the spiritual and material destruction of World War One gave rise to the kind of aggressiveness towards traditional values, and immersion in dreams and the unconscious of such movements as Dada and Surrealism. (2) In fact, the death toll from this pandemic in the early 20th century far exceeded the death toll from World War One, and in an age when pathogens such as viruses were undetectable, it is possible that the fear of the large-scale spread of an illness in which, like in war, the “enemy” was unclear was equally or even more ghastly and hopeless than that of war. Perhaps this is why when we talk about history, while World War One is without exception etched in history books as the most significant event of the early 20th century, until this latest pandemic in the early 21st century became a reality, the ravages brought down on humankind by the Spanish flu had been completely forgotten.

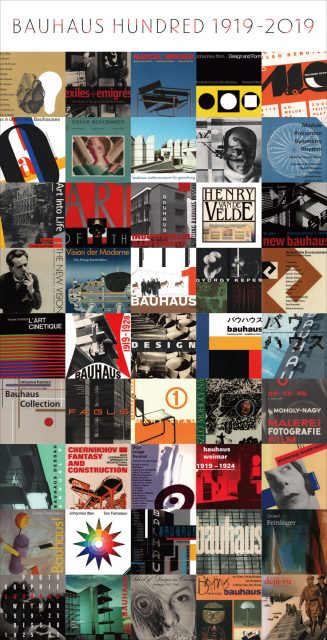

It is not particularly surprising that in order to escape a pandemic that rendered invalid traditional relations among individuals and controllable reality (and hindered even war), artists sought the destruction of visible matter and the flight to dreams. However, until the other day when I heard a new analysis by art historian Toshiharu Ito, I had not considered that the New Objectivity movement in Germany, too, may have been a consequence of the Spanish flu. The occasion was a talk in connection with exhibitions at Book & Design and iwao gallery commemorating the publication of Ito’s new book, Bauhaus Hundred 1919–2019, which also featured Yukimasa Matsuda, who was responsible for the book’s design, and photographer Chihiro Minato. After hearing this analysis, my mind went back to Andersson, who on the eve of the Covid-19 pandemic made a prescient movie that in a similar way looked for a reference source in New Objectivity, at which point the movement, which until then had never really come into focus in my mind, surfaced with a more concrete vividness.

For his 2019 book, exactly 100 years after the founding of the Bauhaus in 1919, Ito chose 100 books concerning the Bauhaus from his own collection and wrote commentaries about them in the form of “100 stories.” During the talk, which was held at a distance from the audience via remote technology amid the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, Ito spoke of how the Bauhaus movement itself arose in the time immediately after the Spanish flu pandemic, how it prompted the New Objectivity movement, and how it is possible to connect these movements to art movements since the onset of the second pandemic in the 21st century as they continue to link up over a wide area (for details, refer to coverage of the talk on this website).

The exhibitions commemorating the publication of Bauhaus Hundred 1919–2019 were held for six days from December 3–5 and 10–12, 2021. (Organizers: Matzda Office / Usiwakamaru, iwao gallery, Book & Design).

The exhibitions commemorating the publication of Bauhaus Hundred 1919–2019 were held for six days from December 3–5 and 10–12, 2021. (Organizers: Matzda Office / Usiwakamaru, iwao gallery, Book & Design).

Historically, the Bauhaus has been viewed as both an educational institution and a symbol of a new set of values based on modern, rationalist design principals that eschewed decoration, revered industrial productivity and function, and pushed to the fore aesthetics and forms made possible by science and technologies such as photography and architecture. Of course, the Bauhaus was not so monolithic, and in its early days it embraced Johannes Itten’s mystical tendencies and a range of peculiar ideas and methods not usually associated with Modernism. However, it is also a fact that when we consider the timing of its sudden rise together with New Objectivity after the Spanish flu pandemic, its mechanical, coolheaded gaze that stares fixedly at (or as Ito puts it, “sees through”) its subjects in a way that is almost unfeeling, and its extreme directionality towards the object, we are driven to an uncanny change in our interpretation of the Bauhaus that cannot be explained simply in terms of rationalism or functionalism.

When I thought about it this way, I sensed I could immediately understand, too, the process whereby at the end of the flow from Bauhaus to New Objectivity there ultimately arose “magical realism.” After all, magic and realism are mutually contradictory. At least in terms of their definition they are. Whereas magic seeks to appeal to something invisible in the depths of reality, realism is a movement whose spirit complies in all respects with that which we can actually see. However, while on the one hand New Objectivity is generally said to possess qualities that run counter to the subjectivity of the expressionism of the preceding period, on the other hand the proximity reminiscent of physical contact to the subject that in New Objectivity is called Sachlichkeit is by no means proximity to the object as contrasted with the subject, but is what we call in English “objectivity,” in which sense New Objectivity cannot possibly be the mere revival of realism.

As with the Bauhaus, the movement of the eyes that perceives the target not as an object as contrasted with a subject but with “objectivity” is accompanied by a gaze into the unknown interior that almost resembles analyzing/dissecting the target using technology, in particular a camera lens. This involves an attitude of severing any relationship with the self and “isolating” at a certain distance (perhaps we could also call this following/tracking, or even tracing) in order to determine not so much the form or color of the target, but the kinds of properties it has as an entity.

And I think one can similarly sense this kind of introduction of objective distance between the self and the subject in Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time, which was first published in 1927 and remains a vital work in the fields of philosophy and contemporary thought.

As mentioned above the Bauhaus was founded in 1919. The Spanish flu pandemic began in March 1918 amid the maelstrom of World War One. The war ended in November 1918, but the pandemic continued even after this, and did not subside until 1919 (and even later in Japan), in which sense the Bauhaus began operating in its very midst. Considering that New Objectivity came into the world as if in response to this at the “Neue Sachlichkeit” exhibition held at the Kunsthalle Mannheim in 1925, it means that Heidegger’s Being and Time was being nurtured in this same environment. In fact, whereas the metaphysics that existed until then had been promoted on the assumption of a theory of knowledge based on questions concerning consciousness and subjectivity typified by Descartes and Kant, in response to these questions, as if carrying on the work of Husserl, who from a position of directionality towards the subject presented the new frame of reference of phenomenology, Heidegger focused not so much on consciousness itself but on its being, heralding the great shift from phenomenon to existence (Dasein).

Perhaps the most important aspect of this shift is that the subject as the seat of consciousness and the object as the target at which this consciousness is directed were brought together within the existence of human beings and contained within ontology as the condition of being known as In-der-Welt-sein (being-in-the-world). If both subject and object are contained within this condition of being, then the schema of subject to object and the distance between that upon which traditional metaphysics was premised no longer come into play. In other words, there is no longer a distance between the two. Distance in the popular sense was embedded within existence, and this implied sense of non-distance can certainly be seen in the depictions of subjects based on the realism that is characteristic of New Objectivity.

Though this is different from the physical distancing adopted as a measure to prevent the spread of Covid-19, it changes into the attitude of “look don’t touch” that naturally arises when we are have to maintain distances between subjects, or to borrow Toshiharu Ito’s expression, into the coolheaded gaze of “seeing through.” And as a result of seeing through, people discover not the form of the subject they are accustomed to seeing, but “a world (not a society) they thought they knew by sight but did not know” as the original state of existence (not reality) that appears when what psychologists call the Gestalt collapses. What brings about this kind of objective identification with a subject that ought to be known but is unknown is magical realism, and here the results of magical intervention and realism are no longer in conflict. Furthermore, the reason New Objectivity is overparticular about being “matter-of-fact” (Sachlich) is in order to discover not objectivity, but the uncanniness of objecthood. In fact, it would be no surprise if at its root lay the shadow of a stranger who may be carrying a virus.

In this way, distance during a pandemic does not begin and end with a concept acquired physically or objectively. If anything, it is this objecthood generating the sense of non-distance that has been amplified repeatedly by the otherness that is a result of this that actually arouses people’s anxiety and concern (Sorge). Given this, one cannot help sense in the ontology advanced by Heidegger, too, a New Objectivity-like coolheaded sense of non-distance towards being.

If there is once again, as Ito claims, a New Objectivity-like tendency in the wake of the 21st-century pandemic, then perhaps Heidegger’s ontology is playing a role in it. Incidentally, as Heidegger’s ontology homes in on its second great theme, time, the philosopher presents “homecoming” (Heimkunft) as a temporality different from physical time, the aspect of time measurable with a clock (which, like the face and hands of clock, is an adaptation of distance). Being and Time itself was never completed, and in his major works Heidegger’s ideas on time were never fully developed, but as a process for approaching primitive time that had been erased by Western metaphysics, which is to say Western philosophy, Heidegger stressed the importance of poetry (Hölderlin), and his contention that it becomes accessible on the way home suggests being (and time) can only be discovered within homecoming itself.

So where exactly is this home? The place to which poetry finally returns is the home of the pillars of Greek philosophy, and in particular the early Greek philosophy that existed long before the prototype of metaphysics as exemplified by Plato and Aristotle. The echoes of their contemplation whose brilliance alone is transmitted to us from afar like a fixed star in the present via such names as Anaximander and Parmenides are what for Heidegger represent the true “classics” and classicism. Given this, if New Objectivity were to take on a neoclassicism-like guise, then essentially it would be premised on a homecoming to an impersonal nature in this kind of sense.

To put it bluntly, this probably means that the place to which existence returns is death itself. After all, homecoming is none other than the revelation of the abyss at the end of the world. Thus, in the final analysis, homecoming is the return to death. Or perhaps it is that death is not something to which one returns, but something that comes after life. But this only applies to the traditional temporal concept of past-present-future that uses space as a metaphor. If time is essentially a homecoming, then in the same way that what comes after life is death, what comes before life, too, is death. If so, then dying could also be a return to death. This may be a perverted way of thinking according to time, space and perceptions of distance based on physics. However, if we take as our point of reference understanding based on life, then death is something that can only be understood in a perverted way to begin with. But what if it is actually the modern concept of time-space that is perverted? It is modern physics that gave rise to this, but just as it was with the “thought” and “extension” of Kant, Newton and above all Descartes, who deserves to be called the founder of modern philosophy, at the heart of modern physics is none other than unnaturalistic metaphysics. By returning to the impersonal nature that existed before metaphysics, we can regain the true reality of being. Here, prehuman nature exercises greater power. This is the unruly nature uncontrollable by consciousness that Greek philosophy prior to Socrates understood. Naturally, death is contained therein.

For this very reason it seems likely that Heidegger regarded death as the fate of existence, and thought that through an “anticipatory resoluteness” (vorlaufende Entschlossenheit) achieved by perceiving in advance this boundary, existence could return to the true reality of being. Of course, by putting it this way we are already transcending such categories as the Bauhaus and New Objectivity. But if these post-avant-garde art movements arose from an understanding in the wake of the Spanish flu pandemic that the unfeeling object and regarding it subjectively were ineffective, then it would seem that in the Bauhaus and New Objectivity, too, the problems of “anticipatory resoluteness” with respect to death and existence (being-in-the-world) were quietly germinating. Yes, New Objectivity is not avant-garde. New Objectivity presented the kind of realism in which the sense of before and after of the avant-garde is lost in time. And this naturally comes close to death. Because amid this kind of naturalism, everything after (and behind) ceases to exist. Since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, it goes without saying that the issue of death has come to feel more familiar to us than ever before. This has undoubtedly created a distance between ourselves and the things we focus on and transformed our gaze, and this in turn has ultimately given rise to a sense of subject-less non-distance between ourselves and these things, nurturing magical realism in the form of things that ought to be known to us yet are unknown, things that ought to be familiar to us yet are unfamiliar.

So where can we find instances of this today? As an example of expression that, like the abovementioned Roy Andersson film, predates the Covid-19 pandemic, has already discovered magical objects through the non-subjective unification of subjects, and most embodies unmeasurably thorough realism (ie, the tracking/tracing with a steady gaze of existence in which time has no context) and the return to death which is even possible before life due to “anticipatory resoluteness” with respect to death (homecoming), I would like to mention Masaharu Sato’s solo exhibition “Trace – absence of presence/presence of absence” held at the Contemporary Art Gallery, Art Tower Mito.

Masaharu Sato – Shortcake (2014), digital painting. Image courtesy imura art gallery.

Masaharu Sato – Shortcake (2014), digital painting. Image courtesy imura art gallery.

View of “Sato Masaharu: Trace – absence of presence/presence of absence” (2021), Contemporary Art Gallery, Art Tower Mito.

View of “Sato Masaharu: Trace – absence of presence/presence of absence” (2021), Contemporary Art Gallery, Art Tower Mito.Photo Naruki Oshima, courtesy Contemporary Art Gallery, Art Tower Mito. (See video clips from some of the works here).

These qualities are most apparent the “Dr. Reaper” series Sato produced after he was told he had terminal cancer and his condition was critical, until he was close to death. Here, rather than approaching his subjects from a certain painterly distance, Sato, who had been forced to leave his beloved home as the end of his life fast approached, depicted the subjects, or rather the objects, that shaped the daily life before his eyes with a realism that is almost unimaginably coldhearted and with an almost complete sense of non-distance, making it is impossible to detect either subjectivity or objectivity in the traditional sense. However, there are no pictures more appropriate to “right now” as the different time available only to those who have resigned themselves to death – and more appropriate to the abstract place that is the “home” to which one endlessly returns as the destination of this “right now.” Below are some comments by Sato that accompanied this series. (3)

Stairs

When I counted the number of steps while producing this work there were nine. I am making good progress with the series, which I started in September, this painting being the ninth. Every day I think the painting I am working on will be my last, so even I am surprised that I have produced so many. Incidentally, the reason I chose these stairs as a motif is because I admire their robustness. Despite being sixty years old, they don’t creak when people go up or down them. The way the surface of the solid, natural wood turns a brilliant golden color when the morning light shines on it at certain times of the year is also satisfying.

Sato Masaharu – Stairs (2018) from the series “Dr. Reaper.” Courtesy Ken Nakahashi.

now

When one is prepared to die, the most important time out of the past, present and future becomes the present. Constantly looking back on the past becomes futile, while imagining the future makes one feel hopeless. It may seem obvious, but after all this time I have come to realize that enjoying the moment that is “the present” (ie, now) is the best way to live.

Sato Masaharu – now (2018) from the series “Dr. Reaper.” Courtesy Ken Nakahashi.

The latter work consists not of a painting but a wall clock. However, the clock has a red second hand only. Accordingly, it simply makes circuits of the same face, the hour moving neither forward nor back. Regarding the act of tracing reality, in distinguishing it from simple objective description or realism, Sato described it as taking the subject he depicts inside himself. One can probably say this is precisely an effect brought about by an awareness of the effectiveness of magical realism arising from New Objectivity, an awareness of being-in-the-world (In-der-Welt-sein). On account of the formidableness of his gaze, the reality traced by Sato no longer appears real. The closer something approaches reality, the more it is estranged from reality and metamorphoses into an unfamiliar object – perhaps this is the sensibility regarding death, something at once unknown and already known, brought about by Sato’s technique of tracing. In fact, it seems as if there is distance between the reality taken inside Sato, the self, and the subject, but there is no distance. Instead there is none other than the way (trail) by which each of us returns home to the state of our own existence as being-in-the-world embedded in the object.

In this sense, between Roy Andersson’s About Endlessness and “Sato Masaharu: Trace – absence of presence/presence of absence” there is something that hints at a new New Objectivity that may come along after the 21st-century pandemic. In both, film becomes painting, and painting becomes film. If we consider them as modes of being, the two are virtually the same. But to do this we require an abyss of time to return to, a sensibility concerning non-distance with respect to endlessness, or in other words finite life and infinite death. For those of us who do not know death, this is something that is unfathomably difficult to embody. However, right now, as an “inevitability” that cannot be avoided, there is at least a “now” that Sato raised from the abyss of time immediately before his death as something that clearly embodies this. And this is by no means unrelated to the homecoming in a different form that is the “domestic” I have dealt with in this column recently.

1. Noi Sawaragi, “Critique1: Jinrui ni totte no saigo no kibō” (The last hope for humanity), in About Endlessness, Japan edition pamphlet, 2019.

2. Noi Sawaragi, “Saegirareru sekai pandemikku to āto 5: Supein kaze no kage – Gendai āto no genryū wa ‘hikikomori’ geijutsu?” (The world closed off by the pandemic and art 5: The shadow of the Spanish flu – Is “hikikomori” art the origin of contemporary art?), Nishinippon Shimbun April 8, 2021, morning edition; republished in the webzine ARTNE https://artne.jp/series/994.

3. Both from the handout distributed at the exhibition, also published in the exhibition catalogue Sato Masaharu: Trace – absence of presence/presence of absence (Bijutsu Shuppan-sha, 2021, p. 175). Compiled as a catalogue raisonné, this catalogue also contains a noteworthy text by Oita Prefectural Museum curator Hisashi Utsunomiya.

“Sato Masaharu: Trace – absence of presence/presence of absence”was held from May 15 through June 27, 2021, at the Oita Prefectural Art Museum, and from November 13, 2021 through January 30, 2022, at the Contemporary Art Gallery, Art Tower Mito.

Note: Similarly, among the works I have seen recently, the grand prize winner at The New Cosmos of Photography 2021, Naotatsu Kaku’s video The Lake, an impersonal view of Lake Haruna in Gunma Prefecture from the time it freezes over to the time it thaws, groaning amidst unpopulated scenery, might also be thought of as part of this trajectory.

About Endlessness, Japan Edition Blu-ray/DVD

Price: ¥5,280 (Blu-ray), ¥4,180 (DVD)

Sales agency:Style Jam

Label: TC Entertainment

©︎ Studio 24