Minoru Onoda: The pulse of “Theory of Propagation Painting” a half-century later

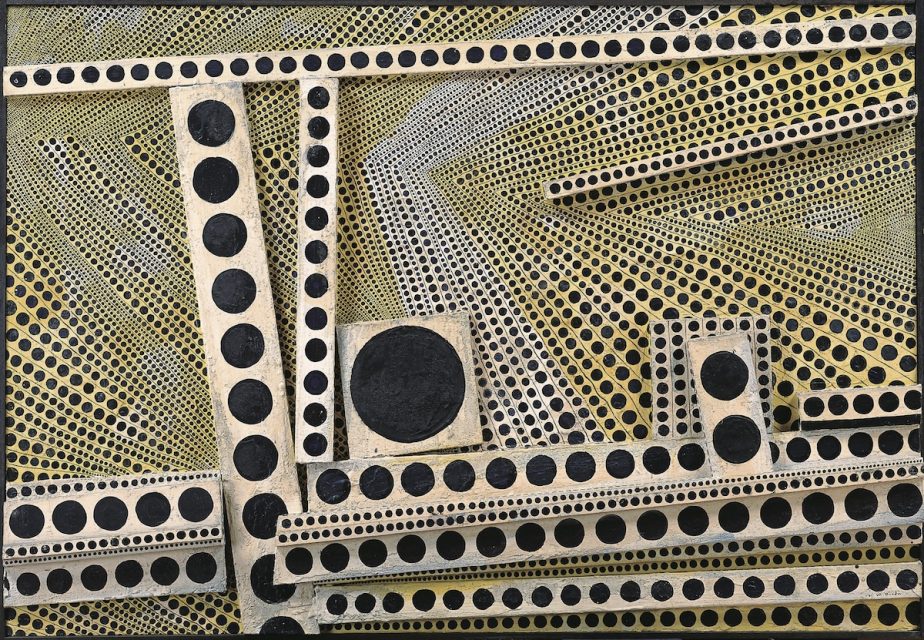

Minoru Onoda – Work 61-11 (1961), 91.4 x 133.1 x 7.4cm, collection Himeji City Museum of Art. Photo Shigefumi Kato.

Minoru Onoda – Work 61-11 (1961), 91.4 x 133.1 x 7.4cm, collection Himeji City Museum of Art. Photo Shigefumi Kato.

On May 15, 2021, eager to learn more about Minoru Onoda’s “My Circles,” I made a long-awaited visit to Himeji. Fortunately (though this may not be the appropriate word), the exhibition venue, Himeji City Museum of Art, which had been closed until a few days earlier in accordance with a state of emergency issued by Hyogo Prefecture, had promptly reopened upon a drop in the number of Covid-19 infections. Having made it to the museum at last, I found almost every single wall covered with various “My Circles” paintings – far more numerous than I’d imagined.

Just how long would it take to view all these circles in every detail? I easily spent two hours inside the venue, which was not nearly enough time. Or rather, for a short while I lost all sense of time. Onoda’s circles have the ability to somehow endlessly absorb the viewer’s gaze, putting one into a state of forgetfulness, like it or not. This I was quickly able to confirm, and that they had something that exceeded my expectations. But what kind of force is at play here?

Installation views of “Minoru Onoda: My Circles,” Himeji City Museum of Art, 2021. Photos Yasushi Kishimoto, courtesy Himeji City Museum of Art.

Installation views of “Minoru Onoda: My Circles,” Himeji City Museum of Art, 2021. Photos Yasushi Kishimoto, courtesy Himeji City Museum of Art.

Circles are the main distinguishing feature of Onoda’s paintings. He began incorporating them into his work as a motif from an early stage, but his representative style of black circles of various sizes proliferating or repeating in all directions on white backgrounds with a yellowish tinge became established from around the time of Work 61-11 and Work 61-12, both from 1961.

These works consist of plywood supports to which long, thin wooden planks have been attached at various angles with adhesive like woodwork. Black circles of various sizes have then been painted on these uneven surfaces using oil paint as if the aim is to completely cover the space from the edges. Moreover, while the grounds of yellow, a color that naturally attracts our attention, are already unusual, the black circles of various sizes are repeated all over following the directions of the planks of wood, while behind them, even smaller black circles are painted in rows, gradually decreasing in size as if being sucked into invisible channels. If one focuses on the large black circles, the smaller circles in the background become blurred, wriggle and begin to float across one’s field of vision like a series of patterns. But if one carefully traces with one’s eyes the individual smaller circles, the black circles on the planks of wood metamorphose, assuming an ominous appearance not of circles, but black holes. Simply by continuing to engage with the paintings while switching between these two ways of looking at the surfaces, one’s field of vision will reel (waver). This is what I meant above when I wrote of a kind of a state of forgetfulness. So precisely how and in what circumstances did Onoda came to create such peculiar paintings? It is not that we have no clues. Regarding their context, Onoda himself wrote as follows in his essay “Hanshoku kaiga ron” (Theory of Propagation Painting), published around the same time.

Some of my recent works are a cynical critique and a jeer at these tendencies, but even in my earlier ideas I was captivated by the image of countless identical parts (these could be symbols or objects) that continue to proliferate mechanically.

From ”Onoda Works 1954-2007” http://onodart.blog94.fc2.com/blog-entry-99.html. Originally published in Himeji bijutsu vol. 1, December 1961; reprinted in Minoru Onoda: My Circle, exh. cat. (Tokyo: Seigensha, 2021).

Here, by “these tendencies,” Onoda means the abstract painting and Art informel tendencies that were hastily imported into Japan on the back of art critic Michel Tapié’s provocative demonstrations during and after the “Exposition Internationale de l’Art Actuel” that toured Japan in 1956. Onoda’s works were primarily both an act of resistance to, and critique of, how the overly emotional and spontaneous painting derived from Action Painting, which called to mind an immediate expression of energy, was subsequently lionized and became a kind of fad in Japan.

However, as Onoda himself writes, even if on the surface his circle paintings were a cynical expression of his response to the current of the times, in his own mind, his opposition to Art informel was by no means the main motivation behind “My Circles.” Rather, it would probably be more accurate to say that for a long time “even in my earlier ideas I was captivated by the image of countless identical parts (these could be symbols or objects) that continue to proliferate mechanically,” and that such “mechanical” proliferation of “countless identical parts” began to take on clear form as images as a result of his opposition to Art informel. Regarding the source of these actual images, in the above-quoted text Onoda clearly gives “factories” as an example.

Most interesting is the multitude of identical products being produced in automation factories. So, for example, vacuum tubes that are produced every day in countless quantities. Only when viewed as an infinite accumulation of tubes, separate from their being embedded in radio or television sets, can one open to the wonder of their vast meaninglessness.

(Ibid.)

So, as a preliminary step to “My Circles,” Onoda experienced both great wonder at the automation systems governing the components produced incessantly in factories and an exceptionally high level of interest in the “vast meaninglessness,” for the time being unrelated to society, arising from this. Given this, perhaps the planks of wood laid on top of the supports in a manner reminiscent of side streets represent production lines carrying the components that crowd and dominate factories. Come to think of it, yellow has almost always been used as a warning color in places like factories (as well as railroad crossings) where the prioritization of inhuman work efficiency and physical danger to humans exist side by side. As well, when arranged alternately, the strong contrast between the yellow, which jumps out from the picture plane, and the black, which recedes, further accentuates the cautionary qualities of yellow and also strongly (malignantly) enhances its visibility. Even apart from such deliberate usages, bright yellow often also serves to warn people of exposure to danger in the natural world through its association with highly venomous bees and poisonous mushrooms.

Speaking of exposing human life to danger, the period when these works appeared was immediately after the military occupation and subsequent reconstruction of Japan and a few years before the first Tokyo Olympics, in the very midst of the expansion of mechanization whose aim was to establish a system in which the whole country valued production above human lives as part of the achievement of rapid economic growth. In this sense, the advent of Onoda’s cautionary paintings consisting of yellow grounds and uncanny black circles was at once a representation of the reality that was undergoing mechanization before people’s very eyes, and a strong disavowal of the popular Art informel that simplistically celebrated physical action.

To realize this image, I chose an infinite number of circles and lines. Since then I have referred to them as “My Circles” and altered their size according to the linear trajectory of the laws of perspective. One can view the picture from any direction. “My Circles” can be extended outward from any point in the picture not only to the wall and ceiling, but also to the road or car. In this way, if you continue to draw a circle anywhere, it becomes my work.

Although it was named “Propagation Painting,” it is not an organic thing like breeding; these are empty, hard-boiled and mechanical images.

(Ibid, underlining added)

In this way, Onoda’s “My Circles” became something decisively separate from the Art informel sensation. They are not spontaneous. Above all, they represent mechanical repetition. In a work representative of this period completed just a few years after the above-quoted text, Work 63-A (1963), one can see that the proliferation and arrangement of the circles that can truly only be called “Propagation Painting” have begun to develop further. But we must not lose sight of the fact that these paintings originate not in “propagation” in the form of biological, organic movement, but above all in a mechanical, automation-like system (not proliferation but repetition), and that for this reason we should regard them as “empty, hard-boiled,” or in other words as dehumanized.

Minoru Onoda – Work 63-A (1963), 91.8 x 91.5 x 5.5cm, collection Himeji City Museum of Art. Photo Shigefumi Kato.

Minoru Onoda – Work 63-A (1963), 91.8 x 91.5 x 5.5cm, collection Himeji City Museum of Art. Photo Shigefumi Kato.

That said, it is difficult to believe that the “mechanical” proliferation of “countless identical parts” was something that suddenly began to dwell inside of Onoda after the war concurrently with Japan’s rapid economic growth. The automatic repetition and proliferation (the mechanical propagation of identical things) appears to have dominated his motivation as a painter and to have firmly taken hold for too long. Looking back on his practice in Himeji, where he set down roots after returning the year before the war ended to Japan from Japanese-occupied Manchuria, where he was born, one can often see in the representational paintings he produced prior to his transition to abstract painting factories and warehouses. Such locations are without exception devoid of people, with the scenes depicted in a detached manner as terminals of a system designed to keep society operating (see, for example, Gasoline Warehouse (A) (1956) and Factory (1958)).

Minoru Onoda – Gasoline Warehouse (A) (1956), 65 x 80cm. Photo Shigefumi Kato.

Minoru Onoda – Gasoline Warehouse (A) (1956), 65 x 80cm. Photo Shigefumi Kato.

Minoru Onoda – Factory (1958), 97.2 x 130.4cm. Photo Shigefumi Kato.

Minoru Onoda – Factory (1958), 97.2 x 130.4cm. Photo Shigefumi Kato.

Perhaps this motivation to dehumanize that led to the later “My Circles” first germinated in Onoda far earlier than this, and can even be traced to his memories of riding on a steamboat on the Songhua River, when he was growing up in Manchuria.

While in the first grade, he took a year off elementary school due to a kidney illness. Around this time, Kiyoshi [Minoru’s father] took him on a steamboat on the Songhua River, a tributary of the Amur. During this trip, Minoru became absorbed not in the vast river or the surrounding scenery, but in the heavy machinery in the engine room.

Uttering “How (does it work)?” and “I wonder why?”, he would freely dismantle toys and other belongings. Such experiences were the starting point for Minoru and among the earliest scenes he remembered.

(Isa Onoda, “Onoda Minoru no koto: “Nande ugokun yaro?” “Nande ka na?” ga chichi no genten” [About Minoru Onoda: “How does it work?” “I wonder why?” were my father’s starting point], in Minoru Onoda: My Circles, exh. cat. (Seigensha, 2021), p. 291.)

Before mechanization was so widespread, it was taken for granted that things that moved repetitively were animals or other life forms. For the young Onoda, the fact that steamboats moved in an organic fashion despite not being livings things must have raised serious questions. When he learned that a steamboat’s driving force was in its engine room, it was no wonder that this became one of the “earliest scenes he remembered.” In this sense, it is not unreasonable to regard Onoda’s “My Circles” as depictions of the way massive mechanical systems operate endlessly without humans almost as if they were life forms, of his fears concerning this and of his personal sense of mystery regarding such mechanisms.

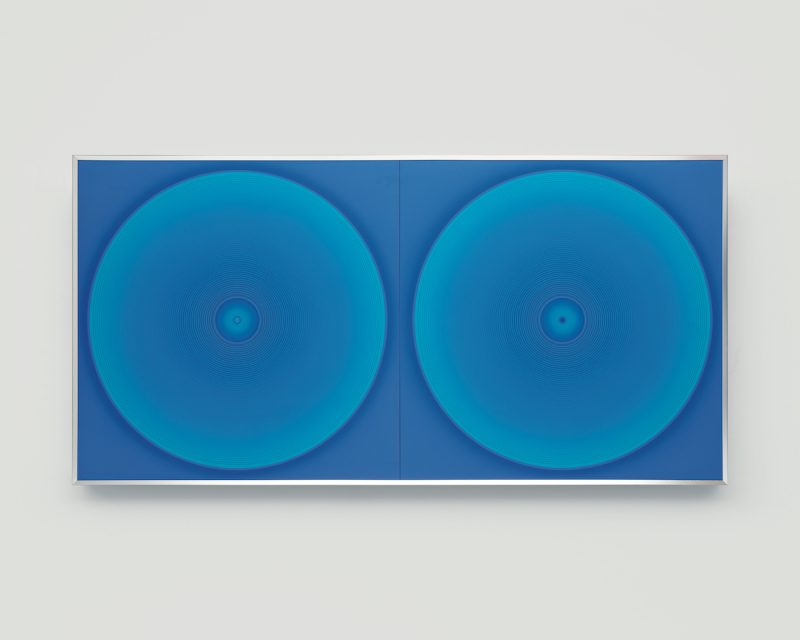

Perhaps it was because such aspects became clearer in his mind, but from around 1966 the “My Circles” Onoda produced changed dramatically, from works with clear material, proliferation-like qualities to singular works in which de-personified “circles” appeared to self-organize into centripetal systems (see, for example, Work 66 R-11 from 1966). In the early 1970s, this tendency finally gave rise to thin, symbolic surface qualities, resulting in works that called to mind not so much machinery but glimmering phenomenological wave patterns generated by machinery. As is clear from the colorful picture planes, there was also a move away from cautionary yellow, with concentric circle-like mechanisms in almost monotonal schemes of blue, red and black becoming prominent (see, for example, Work 75 – Blue 1232 from 1975 and Work 78 – Red 11 from 1978).

Minoru Onoda – Work 75 – Blue 1232 (1975), 80 x 160cm. Photo Nobutada Omote.

Minoru Onoda – Work 75 – Blue 1232 (1975), 80 x 160cm. Photo Nobutada Omote.

Minoru Onoda – Work 78 – Red 11 (1978), 80 x 80 x 2.5cm. Photo Shigefumi Kato.

Minoru Onoda – Work 78 – Red 11 (1978), 80 x 80 x 2.5cm. Photo Shigefumi Kato.

At Himeji City Museum of Art, a wall was erected in the middle of the long, narrow exhibition space dividing it in two, with the organic, proliferate works from the 1960s displayed to the left and the concentric circle paintings with strong symbolic qualities that call to mind complex wave patterns displayed to the right, emphasizing the chronological contrast between the two groups of works. However, Onoda’s system conversion with respect to “My Circles” is not confined to the contrast between these two. In the 1980s and again in the 1990s he established different “My Circles,” his inquiry into these system conversions continuing until immediately prior to his death in 2008. Tracing all of these must wait until another occasion. Here, I would like to introduce in a rough, sketch-like fashion several preliminary ideas not for a retrospective of Onoda’s “My Circles,” but for linking them with different systems and enabling new proliferation/propagation. The first is a system conversion with music.

I originally became interested in this exhibition after hearing about it from Manami Fujimori, a resident of New York who was involved in the translation of the catalog, and after having the good fortune of making the acquaintance of Onoda’s son, Isa Onoda. At the time, I regarded this as a kind of chance encounter, but I had known Fujimori since asking her to arrange for me to attend a performance by the German techno-pop band Kraftwerk in conjunction with their retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, which took the form of concerts staged over seven nights at the museum. That was the year after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and the subsequent meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, so I was greatly interested to see what changes the band might make to their performance of the album Radio-Activity in the wake of those events.

At some point while looking at Onoda’s paintings, which underwent a transformation in the 1970s into works that were not so much organic but called to mind electronic waves emitted in a pulse-like fashion, I was reminded of Kraftwerk’s Radio-Activity. And while this was nothing more than a somewhat crude association truly brought about by chance, remembering that kraftwerk means “power station” in German and that on the outskirts of the city of Düsseldorf where the band formed there is an area with factories called the Ruhr industrial area, I recalled that the starting point of Onoda’s painting was scenes of factories and machinery and detected a kind of associative connection between the two. If such an association were permitted, then perhaps one could also view Onoda’s “My Circles” as “techno-pop (art)” based on a kind of industrial sensibility. Though I was unable to view it, as a related event during this Onoda exhibition there was a live performance by Asa-Chang & Junray with the title “The Theory of Propagation Painting.” In considering Onoda’s paintings, aspects that encourage such intersections of sensibilities give us a glimpse of the possibility of encouraging the expansion of the reception of his work in contexts other than post-war art, and remind us that Onoda’s paintings have “futuristic” qualities that are more than able to withstand such new “propagation.”

The final thing I would like to emphasize is that this universality of Onoda’s paintings, or their ability to work in different contexts, in fact derives from Onoda’s domestic activities as an artist who put down roots in Himeji and continued to create throughout his career with this location as a premise. Or rather, if the word “domestic” invites misunderstanding, one can say that because they are thoroughly domestic, Onoda’s paintings are beyond domestic. On that point, it is probably necessary to add a few words about the art group Neo Art that Onoda formed in Himeji in 1974.

Exactly what kind of art group was Neo Art?

The following is an extract from Bijutsu techo nenkan ’87 published in 1987.

Neo Art Association

Established December 1974. Following the dissolution of the Gutai Art Association, members who developed under Minoru Onoda, a former Gutai member who lived in Himeji, held the first Neo Art exhibition the same year at Hakusan Gallery in Kobe with the aim of carrying on the tradition of Gutai art in Himeji. Two years later, a second exhibition was held simultaneously across four venues along with a contemporary art symposium featuring a panel made up of Sadamasa Motonaga, Shigeru Izumi and Minoru Onoda. Later, in response to a proposal by Masunobu Yoshimura, the group participated in the formation of the Artists Union, subsequent to which it focused its activities on the union movement. In accordance with the supreme directive that creative acts must always be new and original, the Neo Art Association stages exhibitions in a flexible, guerrilla-like fashion with no fixed times or places while continuing to promote the creative activities of individual members.

In summary, Neo Art was started in Himeji by Minoru Onoda with his own followers as its members. Its concept was that “artworks must always be new things that no one has made before.”

(Gengo Ujihara, “What’s NEO ART,” Neo ato 47 nen no kiseki [The 47-year trajectory of Neo Art], Neo Art Commemorative Publication Committee, 2021, p.4, underling added)

The key points are that “creative acts must always be new and original,” and that the guiding principle behind Neo Art’s activities, which included staging “exhibitions in a flexible, guerrilla-like fashion with no fixed times or places,” metamorphosed into activities that burgeoned in Himeji of a completely different dimension than Gutai, incorporating the spontaneous rhythmicity and contingent factory operability of Onoda’s Propagation Painting while inheriting the basic thesis of the Gutai Art Association (Jiro Yoshihara) to which Onoda once belonged. As I have explained repeatedly over several instalments of this column, this seems to have given rise to a position that is neither simply global nor local.

No doubt because of such an “uncommonly” domestic sense of place, Onoda’s “My Circles,” though it originated in his childhood memories of machinery and factories, was repeated over and over again with Himeji as its nursery while changing form organically (in Onoda’s later years the circles changed back cyclically into the holes of his early period), and was able to become “Neo Art” in the true sense of the term, in that it was not limited to what we might call a mere new art trend but truly enabled new, unknown connections.

“Minoru Onoda: My Circles” was held from April 10 through June 20, 2021, at Himeji City Museum of Art.