Art to help us live through these times

Mine Oka and Shunzo Sato (Part 1)

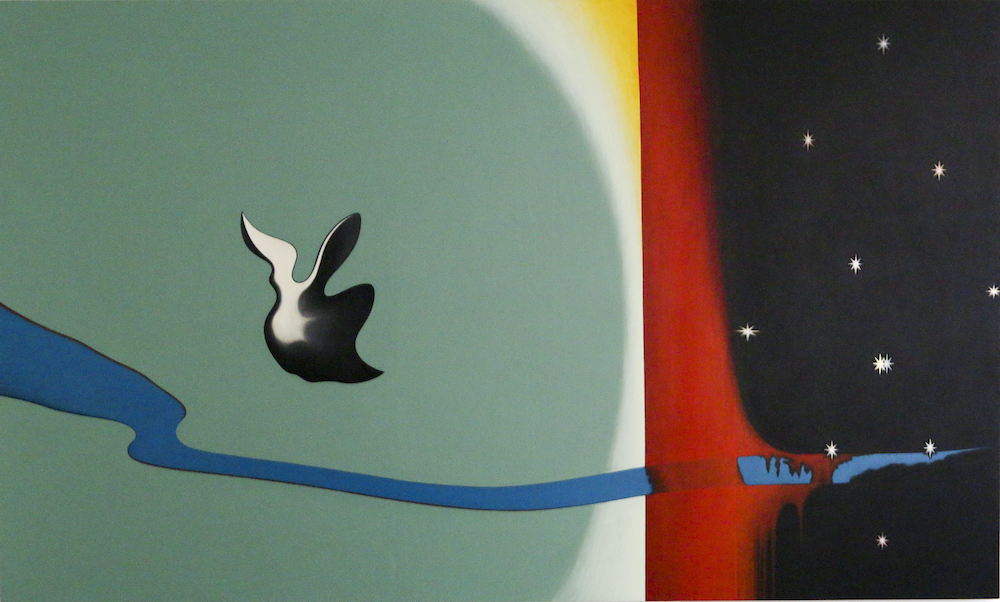

Mine Oka – (left) Night of a full moon – Lake Chapala, (right) Night of a full moon – ¡Adiós!. Installation view at the “98th Shunyo Art Exhibition,” The National Art Center, Tokyo, 2021.

Mine Oka – (left) Night of a full moon – Lake Chapala, (right) Night of a full moon – ¡Adiós!. Installation view at the “98th Shunyo Art Exhibition,” The National Art Center, Tokyo, 2021.

In April, I headed to Nogizaka to see the “98th Shunyo Art Exhibition” being held at the National Art Center, Tokyo. Tokyo was already under a quasi-state of emergency to prevent the spread of Covid-19, and this together with the timing of my visit in the late afternoon meant there was only a scattering of visitors. I practically had the entire spacious venue spanning the second and third floors (51 rooms in total) to myself. Though I was unable to give all of the works a proper look before closing time at 6pm, I was glad I went. For a start, I was overwhelmed by the stark reality that so many people were continuing to produce artworks amid the pandemic. Then due to the declaration of a state of emergency on April 25, the exhibition was cancelled just before it was due to close on April 26. Still, given my long involvement in contemporary art criticism, why did I go to an art association exhibition, something seemingly antithetical to my professional interests? In fact, until now I have hardly ever been to the Nitten or any other such exhibitions.

Broadly speaking, there are three reasons why I went. The main one is that the special advisor to MOCAF (Museum of Contemporary Art Fukushima) – the “art museum” mentioned in my previous column that was launched as a white revolving door approachable from any direction (relativizing entry and exit) in Tomioka, Fukushima, open for just a few hours after the silent tribute at 2:46 pm on March 11, 2021, the tenth anniversary of the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, and later dismantled by hand and partly burned on site as sunset approached – was the painter Mine Oka, who lives in Iwaki and is a member of the Shunyo Art Society. On the “Shunyo Art Exhibition” postcard Oka later sent me he had written, “Let’s both survive the coronavirus pandemic,” a reference, I perceived, to “art to help us live through these times.” I really wanted to see Oka’s new work in Tokyo, where the pandemic was raging furiously.

The second reason has its origins in Kyoto, where I had travelled on several occasions while the “Bubbles / Debris: Art of the Heisei Period 1989-2019” exhibition was on at the Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art. During my stays there, I fitted in visits to a number of galleries around Kyoto. Seeing as it was so long since I had stayed in Kyoto for a prolonged period, I was visiting them all for the first time. One of these galleries was Gallery Hill Gate in the Teramachi Shopping Arcade. Like the “Shunyo Art Exhibition,” this is a gallery that has concentrated on projects that are quite different from the kind of contemporary art I have focused on until now.

There was a particular reason why I headed to Gallery Hill Gate. I heard from Yukinori Okamura, curator at the Maruki Gallery for the Hiroshima Panels in Higashi-Matsuyama, Saitama – where the exhibition I curated of work by the “forgotten” photographer Katsumi Sunamori, “Implications of the Scenery,” was held in 2020 (see Notes on Art and Current Event 89-91), intermittently, due too to the impact of a state of emergency – that Junko Hitomi, the owner of Gallery Hill Gate, wanted me to visit the gallery. Okamura had visited Kyoto earlier this year for the exhibition “Maruki Iri: A Retrospective” held at Gallery Hill Gate, on which occasion I had apparently become the topic of conversation. It seems that the late art critic Ichiro Hariu would almost always stop by at Gallery Hill Gate whenever he was in Kyoto, and often wrote while relaxing in the cafe that occupied part of the gallery’s second floor. It was from Hariu that Hitomi had first heard my name.

Visiting Gallery Hill Gate made me think again of Hariu, and I recalled how he disliked distinguishing between contemporary art and so-called art association exhibitions, believing that great artists were not influenced by their affiliations.

Of course, contemporary art is not an association. If anything, it arose as a resistance force against associations backed systematically by open-entry exhibitions and members. However, having come to feel that at some point contemporary art had begun to behave as if it were an association, spurred on by Hariu’s words and at the same time recalling “art to help us live through these times” inspired by Mine Oka’s message from Iwaki ten years after the Tohoku quake, I set off down a path that would lead through the entrance to the “Shunyo Art Exhibition” as a “door” that was completely unknown to me.

The third reason relates directly to the “temperature of the time” touched on in the previous installment of this column, “ART/DOMESTIC 2021.” Following the example of Takashi Azumaya, who under a global system curated “ART/DOMESTIC Temperature of the Time” (1999) as a counter-concept to “art/global,” which had become an icon-like body/index without mass and flew around the world trying to see how far it could get from a close (domestic) temperature, as if to defy the pairing of “national/local” (eg, glocal) that is none other than being absorbed by globalism, I introduced a concept of “domestic” that was neither national nor local, resulting in the title “ART/DOMESTIC 2021.” Of course, it is hardly likely that such domestic art will belong exclusively to the cutting-edge art world. Because for a start, what I refer to here as “domestic” is art that is at once rooted in the many-times folded, topographically congested place we call the Japanese archipelago and possessed of a strangely familiar sense of temperature, and, whatever it is, does not belong to the existing system. Ands an artist who has such a peculiar sense of temperature, Mine Oka came to mind.

Immediately after I proposed “ART/DOMESTIC 2021,” there was an interesting response to my criticism from Yutaro Midorikawa, director MOCAF (“ART BEYOND DOMESTIC,” Midorikawa’s website, April 1, 2021). According to Midorikawa, while “art is ‘domestic’ to begin with,” at the same time it needs to be “beyond domestic.” In other words, it is precisely in order to go beyond being domestic that art needs to be domestic, and being domestic itself does not constitute a goal or a slogan. I should quickly add that Midorikawa did not wish to contradict my “ART/DOMESTIC 2021” proposal, but merely added his opinion that only by being not just domestic, but “uncommonly domestic” could art be “beyond domestic.” This is absolutely the case, evidenced by the fact that in “ART/DOMESTIC 2021” I dealt not with art that was merely systematically domestic, but none other than MOCAF, an “uncommon” art museum that within hours was dismantled and turned into firewood.

So perhaps the world I entered on March 11, 2021 after passing through that revolving door at MOCAF in which entrance and exit were relativized was none other than the “Shunyo Art Exhibition” during the coronavirus pandemic, as an “ART/DOMESTIC 2021” site in which meaning had changed 180 degrees from that of a showcase for domestic painting in the common sense of the term. In fact, in his critical response, Midorikawa wrote as follows:

For a start, one can say that the condition of the MOCAF site and the people who gathered there on March 11, 2021, were “domestic” (the people were not passersby who gathered without notice, but people who gathered with complexly interwoven relations, circumstances and reasons). One can further say that the people for whom something changed due to the MOCAF door opening were people who ventured beyond the “domestic” (there are probably people for whom nothing changed even though they are interested in art, and people for whom something did change even though they are not interested in art). MOCAF is a museum, but one could say that the “peculiar” moment or space-time arising from that revolving door is ART BEYOND DOMESTIC.

In a sense, spread out before me after passing through the MOCAF revolving door were the two paintings by Mine Oka that I encountered in a corner of the “Shunyo Art Exhibition” as my very own “art beyond domestic,” or “art to help us live through these times/beyond domestic.” When I mentioned in the previous installment of this column the “50th Iwaki Citizens’ Art Exhibition,” a premonition of this encounter was undoubtedly already embedded in my mind as a kind of low-grade fever. I say this because the first time I encountered the totality of Mine Oka’s painting was at the retrospective “Mine Oka – Journey to Calavera” held at the same Iwaki City Art Museum in 2018.

Installation views of “Mine Oka – Journey to Calavera” (2018), Iwaki City Art Museum.

Installation views of “Mine Oka – Journey to Calavera” (2018), Iwaki City Art Museum.

Given that so few people had the chance to read the text I wrote for that exhibition, to the extent that it demonstrates the possibility that the “uncommonly domestic” may lead beyond the local, the national and even the global to connect as is to earthly (planetary) space-time, I think it is worth reproducing it here. Allow me first to note that based on the premise of ground that is “uncommonly domestic,” ground continually shaken by earthquakes that might also be called the heat of the earth, Mine Oka’s paintings are closely connected to my book Shin bijutsuron (Earthquake art theory), which examines the state of art “that takes root/cannot take root, lives/cannot live.”

Two major earthquakes have cast their shadows over Mine Oka’s career. Given that he was born in Iwaki, Fukushima, it goes without saying that the 2011 Tohoku earthquake was of great significance to Oka. But it should also be noted here that it was the major earthquake that struck Mexico in September 1985 that put an end to Oka’s stay in that country, which though intermittent lasted for 11 years and had a tremendous influence on his style. The magnitude of this earthquake that occurred on the seabed near Lázaro Cárdenas, a city facing the Pacific Ocean, was 8.0. A tsunami also occurred nearby, but the greatest damage occurred a considerable distance inland in Mexico City, a city built on ground that contained a lot of water and was unstable to begin with. It was unable to withstand the prolonged shaking triggered by the quake, resulting in liquefaction, the collapse of many buildings and the deaths of nearly 10,000 people according to officially confirmed figures alone. At the time, Oka was living on the shores of Lake Chapala, Mexico’s largest lake famous for its scenic beauty and known as an artist colony, near Guadalajara. One can imagine how much of a shock this quake must have been for Oka, who had long used Mexico as a source of creative inspiration.

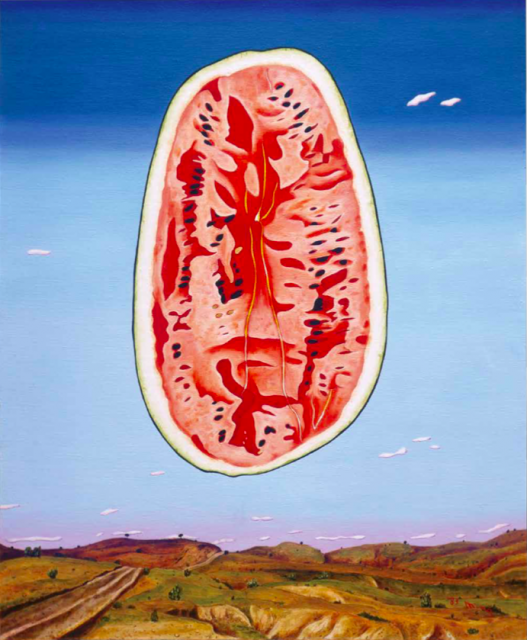

Mine Oka – Adios (1976).

The prime motif Oka encountered in Mexico was the calavera, or human skull. Unlike in Japan where they are regarded as inauspicious, in Mexico representations of skulls are often the centerpieces at lively, colorful festivities celebrating the resurrection of the dead. Far from being symbols of death, calaveras are the very proof of life rising from under the ground, able to celebrate life more passionately than the living, who can only wait for the death that will eventually come. Because they are already dead, neither are they frightened of the shadow of death. Their overly cheerful appearance signifies their having been completely freed from the anxiety of death. But what about the people who had just died in the Mexico earthquake? Those dead, far from returning to the ground had only just left this earth, needed not festivities but repose and consolation, enough to overturn the meaning of calaveras, albeit temporarily. From around this time, sections of split watermelons and riotous profusions of scarlet flowers began to appear frequently in Oka’s paintings. In section, the red watermelons, which incorporated a lot of water and called to mind the fragile earth on account of their many ruptures, took on the appearance of earth that had cracked and soaked up blood, while the scarlet flowers resembled floral tributes to the dead that had been sucked through these cracks and fallen into the depths of the earth. Or perhaps one should say (as is often the case with the motifs Oka selects) they anticipated these events.

Mine Oka – (left) Road to Revolution (1983), (right) Portrait of Senora T (1994).

Curiously, it was from around the time of the 1995 Hanshin-Awaji earthquake that large numbers of fish also began appearing in Oka’s paintings. Having wanted to become a sailor as a youth wanted, the sea was undoubtedly an indelible image in Oka’s mind, but perhaps his memories of earthquakes caused him to express as fish, a form of life adapted to the sea, how fragile the earth is in comparison. Later, prior to the 2011 Tohoku quake, these fish metamorphosed into anglerfish that live in the dark depths of the sea as “philosophizing deep-sea fish.” At some level it is if they had inherited the baroque (in the original sense of “a pearl of irregular shape”) characteristics of his earlier watermelons and scarlet flowers.

Mine Oka – Alchemist breaking the seal (2015).

What exactly are “philosophizing deep-sea fish”? What are fish that think in the pitch-black darkness of the deep sea beyond the reach of sunlight? This is a world diametrically opposed to the Mexican sunlight, so dazzling it burns ones eyes. And yet, the anglerfish that live in this darkness are surprisingly richly colored. In Japan, catfish have long been depicted as the cause of earthquakes. A major difference between this and Oka’s work is that the anglerfish are shaking not in attempt to trigger quakes, but because they are raging. In the deep sea where they go unseen, their brightness is meaningless. But is true life not the celebration of life expressed even in the darkness of the deep sea where no one sees it? No, celebrations of life have now transcended joy to become anger, and have metamorphosed into coelacanths, also known as “living fossils,” continuing their intense thinking on life while shaking with anger at the absurd life and death that have remained unchanged for 350 million years. Does not their appearance almost resemble calaveras that have sent themselves into the deep sea?

Noi Sawaragi, “The paintings of Mine Oka – The road from calavera to coelacanth,” 2019, self-published.

*Images were borrowed to post with this reproduction of the text.

If earthquakes are phenomena triggered by primordial fluid heat remaining in the earth’s womb, then perhaps we can call the mode of this heat not the “temperature of the time” but the “temperature of the earth.” Here, however, “domestic” has already expanded to the scale of the planet (not the world/global). Perhaps because it is “uncommonly domestic.” Places where this literal “heat of the earth” can be felt are especially numerous in Japan, one of the world’s main volcanic zones, and Iwaki Yumoto, mentioned in my previous column as the reason behind my becoming involved in the radiation-affected area in Fukushima, is at once a coal-mining town from long ago (coal an underground manifestation of the temperature of the earth) and a resort famous for its hot springs where the “temperature of the earth” can be felt directly, on a personal level.

Speaking of which, Beppu in Oita Prefecture, which I have been visiting practically every year since the first Mixed Bathing World international art festival was held in 2009, is also one of Japan’s leading hot spring resorts, top in terms of diversity due to the sheer quantity of its hot spring water and the richness of that water’s colors and constituent elements. Steam shoots out everywhere and smoke constantly billows into the air, so much so that when I first visited Beppu I wondered if there were fires burning all around the town giving off smoke. The hot springs at Beppu are extremely hot and dangerous, and for a long time they were feared as “hells” because people could not live near them or engage in farming and even trees and plants would not grow. Now, however, the hot springs have become a valuable tourism resource and a “blessing” in that not only daily baths but steam cooking are considered indispensable parts of daily life.

Beppu is also a place that has important meaning in Shinbijutsuron (Earthquake art theory), in which I discussed the connection between earthquakes and art. Beppu Bay, a bowl-shaped body of water extending out from the town of Beppu, is the birthplace of a legend according to which Uryu Island – where the ancestors of Arata Isozaki, an architect who occupies an important position in the book, once lived – sunk to the bottom of the bay in a single day as a result of an earthquake and tsunami that struck the region in the Keicho era. With the Japanese archipelago being not solid “ground,” but continually shaken by the “heat” hidden underneath it, from the viewpoint of anti-architecture and anti-art that render everything on the ground fluid, Beppu Bay could also be called a kind of boiling point. It was in March at this geothermal hotspot of Beppu that I received word from an acquaintance of an art exhibition beginning in Oita the day after my arriva: “Rainbow, Summer Grass, Softshell Turtle: All About Shunzo Sato.”

Installation view of “Rainbow, Summer Grass, Softshell Turtle: All About Shunzo Sato,” Oita Art Plaza, 2021. Photo Yuji Shinomiya, courtesy the Shunzo Sato Exhibition Executive Committee. The exhibition website features a virtual walkthrough of the exhibition.

Installation view of “Rainbow, Summer Grass, Softshell Turtle: All About Shunzo Sato,” Oita Art Plaza, 2021. Photo Yuji Shinomiya, courtesy the Shunzo Sato Exhibition Executive Committee. The exhibition website features a virtual walkthrough of the exhibition.

Shunzo Sato – Twilight (1993). Photo Mami Fukuzoe, courtesy Shunzo Sato Hananoki Museum.

Shunzo Sato – Twilight (1993). Photo Mami Fukuzoe, courtesy Shunzo Sato Hananoki Museum.

Unlike Beppu and the picturesque places like Yufuin that lie behind it, Oita, which comes into view after driving along the coast of Beppu Bay from Beppu, has the appearance of a laid-back city that is the seat of the prefectural government and little else. However, the full extent of the anti-artistic heat that lies hidden there cannot be gathered from its exterior. Constructed in Shinjuku in the early 1960s according to a design by none other than Arata Isozaki, Shinjuku White House is known as the former base of the Neo-Dada Organizers (commonly referred to as Neo-Dada), but Isozaki, the building’s owner Masunobu Yoshimura, and the most radical actor among the group Sho Kazakura were all originally from Oita. In this sense, it is no exaggeration to say that a considerable part of the Neo-Dada anti-art movement drew its strength from the heat of the domestic location of Oita. “All About Shunzo Sato” took place at Oita Art Plaza, which was designed by Arata Isozaki and has a permanent exhibition featuring many Neo-Dada works by among others Yoshimura and Kazakura.

Oita Art Plaza (Architect: Arata Isozaki)

Oita Art Plaza (Architect: Arata Isozaki)

Nevertheless, upon hearing his name, hardly anyone is likely to be able to conjure an image of Shunzo Sato’s work. But this is understandable. Even in his home of Oita, Sato is an “unknown artist,” and this exhibition, held to mark the tenth anniversary of his death, was realized due largely to the efforts of his supporters (Keiichi Ninomiya and Hidekazu Kimura) along with his remaining family and others who run the Shunzo Sato Hananoki Museum (Hiji, Oita), a private museum where Sato’s paintings are on permanent display. It is a classic example of “domestic” art rooted in its location. But it is not merely local. Rather, this is a group of works that is “uncommonly” domestic, possessed of a familiar and specific heat, going beyond the global to became “planetary” to an extent far greater than any contemporary art, and in this sense it is far more vivid than any concept constructed within the bounds of the human intellect, endowed with strength from and an expression of the “temperature of the time.” The statement by the two above-mentioned supporters in the flyer produced for the exhibition conveys this extremely simply, so I will reproduce it here.

Shunzo Sato, who hails from Hiji, Oita Prefecture, was an outstanding painter. He was also a man who enjoyed physical labor. He built his own studio in the wooded hills of Oga, Hiji while earning a living through farm work.

Sato named this studio surrounded by trees “Hananoki Toride” (Fort Hananoki). “Hananoki” derives from a local placename, but it is unusual to call a creative space a “fort.” Perhaps he wanted to do battle with something, or protect something. After all this time, we still do not know.

What is certain, however, is that inside this “fort” he reflected long and hard on himself, repeatedly engaged in dialogue with nature and the universe, and continued his prolific art practice. On this frontier, so to speak, he quietly and confidently filled his days with physical labor and art. One could say that Sato’s way of life of establishing his own practice in a form that involved neither the teaching business nor the art business was an exceedingly honest and new way of living.

If he had continued living, this existence would probably have influenced many people, but regrettably he died of cancer in 2010. He was 56 years old. The more than 200 painting he left behind are all original and of a high standard. Despite this, his achievements are almost completely unknown even in Oita Prefecture.

To mark the tenth anniversary of his death, we are holding two large-scale exhibitions in an effort to inform as many people as possible of Shunzo Sato’s life and work. We hope that as many people as possible will enjoy the world conjured by his art.

Shunzo Sato Exhibition Executive Committee

Representative: Keiichi Ninomiya

Secretariat: Hidekazu Kimura

He “enjoyed physical labor” because he experienced the heat inside his body, “built his own studio in the wooded hills of Oga, Hiji while earning a living through farm work,” and “inside this ‘fort’ he reflected long and hard on himself, repeatedly engaged in dialogue with nature and the universe, and continued his prolific art practice.” In the present age of the coronavirus pandemic in which the journey ahead is uncertain, from a phase different from the global and the local, not to mention the national, rather than rushing around the world in an instant, it would seem that this path followed by Sato is highly suggestive as “an exceedingly honest and new way of living” for a domestic (planetary) artist “on this frontier, so to speak, […] quietly and confidently fill[ing] his days with physical labor and art.”

Shunzo SatoHomo sapiens (1997). Photo Mami Fukuzoe, courtesy Shunzo Sato Hananoki Museum.

Shunzo SatoHomo sapiens (1997). Photo Mami Fukuzoe, courtesy Shunzo Sato Hananoki Museum.

Shunzo SatoThe tortoise and the hare (2002). Photo Mami Fukuzoe, courtesy Shunzo Sato Hananoki Museum.

Shunzo SatoThe tortoise and the hare (2002). Photo Mami Fukuzoe, courtesy Shunzo Sato Hananoki Museum.

But space forbids me from going any further on this occasion. And as indicated in the text reproduced above, there are “two large-scale exhibitions” dedicated to Shunzo Sato comprising “diffusion” and “condensation,” their character and venue being completely different. So far I have only actually been able to view the latter, in which Sato’s paintings are “condensed,” but in my next column I would like to write in more detail about these two exhibitions, including the “diffusion.” For now, I will restrict myself to noting that Sato was at once an outstanding painter and a poet with an extremely acute sensibility, and that the words that serve as a medium linking these two exhibitions, “rainbow, summer grass, softshell turtle,” are also the title of the poetry collection he left behind, indicating that for Sato, painting and poetry were almost inextricably linked.

What a glorious scene the words “rainbow, summer grass, softshell turtle” evoke. While limiting the elements to things visible nearby, the association of these words has an astonishing global expansiveness. Because through the medium of fresh summer grass that grows to our eye level, small lives that crawl through the mud at our feet in accordance with the laws of gravity and multicolored rainbows as optical phenomena in the atmosphere, mud and rainbows, turtles and light, small lives and the universe that extends out around them immediately encourage a leap of consciousness that extends in a vertical direction. And in fact it seems that Sato’s paintings, too, are simultaneously endowed with this kind of human scale and ability to leap. (To be continued)

The “98th Shunyo Art Exhibition” was held from April 14 through 25, 2021, at the National Art Center, Tokyo.

“Rainbow, Summer Grass, Softshell Turtle: All About Shunzo Sato, was held from March 17 through 30, 2021, at Oita Art Plaza. The Shunzo Sato Hananoki Museum (Hijimachi, Oita) displays primarily works by the artist year round.